Book Review: “As It Turns Out” — Not Enough About Edie and Andy

By Peter Walsh

Alice Sedgwick Wohl has a disturbing tendency throughout the book to back away from her points even as she makes them, as if afraid she will find herself trapped in some politically incorrect cul de sac or just a bad neighborhood.

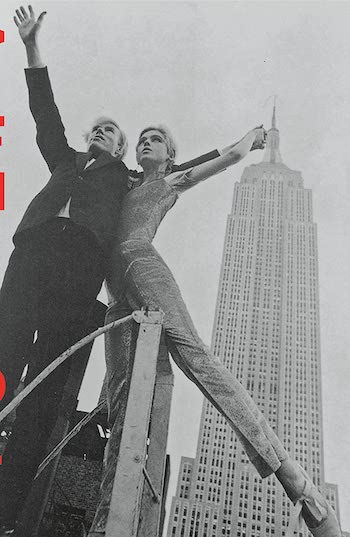

As It Turns Out: Thinking About Edie and Andy by Alice Sedgwick Wohl. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 272 pages, $28.

Cover art for As It Turns Out.

In the spring of 2019, the story goes, Alice Sedgwick Wohl and her art historian husband were visiting the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover. There, unexpectedly, she encountered, on a large video screen, a double image of her younger sister, Edie, in a clip from the Andy Warhol film Outer and Inner Space, which apparently she had never seen.

Coming on the much enlarged face of your very famous but long-dead sibling in a public place without warning would be enough to unsettle anyone. She was fascinated, Wohl says at the beginning of her new book As It Turns Out: Thinking About Edie and Andy, by the images of her sister, mirrored on the screen by her own image behind her on a monitor. Wohl has a sudden revelation of what she had missed in the half century since Edie’s death— “what Andy Warhol made of Edie Sedgwick.” She is sure her late brother Bobby would have understood, too.

The exact nature of the revelation, though, has to wait until near the end of the 244 pages that make up this odd book.

It’s probably been a couple decades since I thought much about Edie (Edith Minturn) Sedgwick, the American model, actress, and Andy Warhol intimate who died in 1971 of a drug overdose, aged 28. In fact, she’s probably been more or less out of my mind since I read Jean Stein and George Plympton’s Edie: An American Biography (1982), a book that revived her once-incandescent fame. Yet, for generations born long after mine, Edie has remained a meme for at-the-edge art and fashion, unassailable social status, hyperized celebrity, riotous fast living, and beautiful, doomed youth. Only briefly alive, she still haunts the streets and lofts of the imagined ’60s.

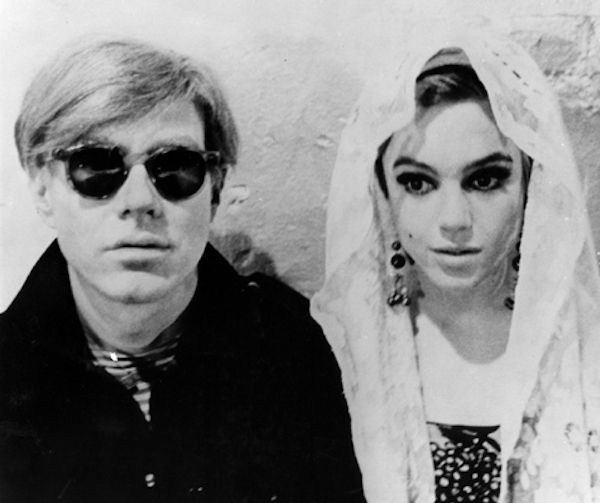

Edie was a much-photographed member of Warhol’s inner circle during the height of his “Factory” era, “superstar” of many of his underground films, proclaimed a “Youthquaker” the “It Girl,’ and “The Girl of the Year [1965]” by the hyperventilating media and, for a few months, Warhol’s constant companion at avant-garde New York social venues. Her image is imprinted on mid-20th-century American art and popular culture — the unmistakable face, with its short hair and trademark heavy eyelashes and mascara, can turn up, without warning, almost anywhere.

Mostly told in the chronological narrative of memoir, As It Turns Out travels through several abrupt changes in style and tone that suggest it may have begun as parts of two or three different texts: a personal memoir, an account of Edie’s life in the central year of 1965, and a meditation on its significance, addressed to their brother, Bobby, who died in a motorcycle accident in 1965, only months after another brother had committed suicide.

After a short foreword that describes the encounter in the Addison Gallery, the book moves into a section called “The Past.” The longest part of the book, it has little to do with Edie — she isn’t even born for dozens of pages. Instead, Wohl provides a soft-focus description of her own childhood, growing up in a rich family in California.

The Sedgwicks, we gradually learn, are an old money, waspy family with roots in central Massachusetts and branches in Boston and New York. The boys all go to Groton and Harvard; the girls are expected to marry young. Wohl mentions parts of her heritage in passing. There was a speaker of the US House under Thomas Jefferson, prominent generals in the Revolution and Civil War, the longtime owner-editor of The Atlantic (his estate north of Boston, Long Hill, with its celebrated garden, is now maintained by the nonprofit Trustees of Reservations), a popular historian. Wohl’s own branch, after her parents marriage in 1929, settled in California on an elegant estate named Goleta outside Santa Barbara, a wedding gift from her maternal grandfather, an investor and railroad executive who seems to have subsidized the growing family (there are eventually eight children) for years.

Wohl describes a life of such wealth and privilege that it flirts with the absurd. At first, the family divides its time between Goleta and a house in Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island near their New York relatives (they are bicoastal before the era of jets, traveling by rail over several days twice each year). Wohl’s parents seem to have defined “privilege” not only as luxury but isolation from anything that might be disturbing or upsetting to their idyllic way of life.

Alice Sedgwick Wohl. Photo: FSG

Wohl grows up in the ’30s and ’40s yet she never mentions the Great Depression. Her only childhood encounter with poverty is the sight, from inside a car, of some hoboes by the side of the road. At a time when many of her American contemporaries were deeply engaged in following World War II and their relatives who served in it, Wohl only mentions the conflict when it touches on her own family — for example, when explaining that her father never served, despite his robust physical condition, probably because of his always fragile mental health. No one in her family ever talked about the war, Wohl explains. She and her siblings spend their time among family and her parents’ friends; the only people of other social classes she knows as she grows up seem to have been servants or family employees.

Later, the family moved its primary residence to a large rural cattle ranch, close enough to Goleta to spend weekends there. Wohl and her siblings move into converted bunkhouses. Each has a horse to ride and they help with ranching chores (the heavy work all seems to have been done by hired hands). It is a lifestyle that would turn little girls green with envy. But young people of the Social Media Age might be shocked at how dull wealth and privilege could be. There is no TV and hardly even radio, no malls or even much shopping, no smart phones, no Internet, no selfies, and few connections at all to the outside world. The children are instructed not to stand out or to call attention to themselves. The standards of upper class dress codes Wohl is taught are so dim and modest that she is fascinated by the bright colors and conspicuous jewelry of the Californian women her parents invite to their home. She had never balanced a checkbook or taken a public bus, trolley, or subway until she moved to Cambridge as a Radcliffe College student.

The strikingly handsome, ambiguous figure of Wohl’s father, Francis Minturn “Duke” Sedgwick, whom she calls “Fuzzy,” rules over it all like a real duke. Never employed by anyone else, periodically afflicted by mental illness, Fuzzy works as an artist and also dabbles in novel-writing and work on the ranch. Wohl can never quite decide whether the life he creates for her is benign or monstrous, though she later attributes many of Edie’s, and her own, problems to her parents’ controlling hands.

Well into “The Past,” Edie is finally born. Wohl is almost a teenager then and is mostly away at boarding school and college as Edie grows up. The youngest children have been moved to a separate household on the ranch, with a nanny and their own staff. Eventually the family moves to an even larger ranch that is even more remote. Thanks to conflicts with her parents that Wohl only alludes to (at one point things get so bad her father cuts off her tuition at Radcliffe and tries to destroy her reputation at the school, for reasons never explained), she doesn’t visit her family for years at a time. When Wohl sees her again, Edie is already a young woman. It becomes clear that Wohl barely knew her sister.

By the time she’s the focus of the story, moreover, Edie is already a mess: spoiled rotten, reckless, extravagant, empty-headed with already bouts in mental hospitals as a teenager. Later Edie declines still further into serious eating disorders and the drug abuse that eventually kills her. Wohl rants about Edie’s skill at manipulating her parents into giving her everything she wants — and it’s a lot — when Wohl herself had to grow up with so many painful, if largely undescribed, restrictions.

As “The Past” comes to an end, Edie is college age and living in Cambridge. Surrounded by a group of eccentric friends, she makes a splash in the ivy-edged Bohemia of ’60s Harvard Square. She’s soon a fixture at once famous, now long-gone local night spots like Casablanca. In the summer of 1964, after Cambridge empties out for the season, Edie migrates to New York. There her life becomes even wilder and more extravagant. She’s involved in two serious traffic accidents, but her circle widens and extends to Bob Dylan. (Wohl attributes the Dylan songs “Just Like a Woman” and “Leopard Skin Pill-Box Hat” to his encounter with Edie, though she never quite claims it was romantic.) Edie, subsidized, Wohl assumes, by their mother, travels around town in limos and burns through, Wohl suspects, several hundred thousand dollars of her parents money before they finally rein her in. Then she resorts to shoplifting.

Wohl is living in New York as well. But apart from an awkward chance encounter at her grandmother’s New York apartment, where Edie is living, Wohl sees and hears nothing of her or her new friends. One evening in March of ’65, Edie shows up at Wohl’s apartment with a gift (from Tiffany’s) for the Wohl’s little boy. She doesn’t stay long. Wohl is in her 30s. At this point, Edie is still 20 and has not yet met Andy Warhol. She would live for another eight years. Wohl never sees her in person again.

After “The Past” is over, Wohl drops entirely out of the narrative. She has hinted at broadening social horizons and the beginnings of a social conscience but we hear nothing more of her adult life, her second husband (her first marriage had ended in divorce), their family, her career (she is best known for her translation of Italian Renaissance texts on art and artists), where she lived, who she knew, or her later relationships with her parents and siblings. In the next section, “1965,” As It Turns Out turns to Edie.

Edie Sedgwick and Andy Warhol. Photo: Wikipedia

“1965” is an abrupt change in tone and approach. The style is informal and knowingly indulgent, not very different from the style Warhol used in his diaries and other autobiographical writings. It also takes a page or two from the brand of narrative journalism, built up from sources, made popular by writers like Bob Woodward. The narrative is now full of character sketches, anecdotes, and telling detail — all of which were largely lacking in “The Past.” Almost instantly on their meeting, we learn, Warhol was entranced by Edie’s beauty, WASP heritage, wealth, and uncanny ability to command a room or a screen with her image. And eager to make use of them.

Wohl writes long passages on Edie’s films and describes her sister’s life as part of Warhol’s inner Factory circle month by month, as if she were right at her elbow most of the time. Only she couldn’t have been, since, as we know, she never saw Edie in those days at all.

As It Turns Out doesn’t use numbered footnotes or an academic apparatus, but the notes at the back of the book reveal “1965” was made up from research: contemporary news reports, articles, and the many books written about Edie, Warhol, and the Factory years, including the Stein biography, for which Wohl was a source (Stein, she says, was an old school friend). Wohl’s text is full of little tells: “[a]s Ronnie Tavel put it…,” “[i]n Steven Watson’s words…,” “Ondine, who told Victor Bokris… ” “[Charles Henri] Ford recalled…” “[i]t is worth quoting from Callie Angell’s lucid account…” “[h]ere’s Andy’s own description of what happened.” Wohl seems to make all the journalistically required attributions and never actually says she witnessed any of this first person, or claims to draw any of her conclusions about Andy, Edie, and their circle from her own first-hand experience. But the casual reader, who doesn’t check the back of the book, could easily get that impression.

Wohl eventually admits she never actually knew her sister. She apprehends her life (like almost everyone else) through her many media images. That doesn’t prevent her publisher from framing this memoir as an insider’s view of Edie and Andy’s world. This is a bit of a bait and switch.

In a concluding section, “Notes for My Dead Brother,” Wohl returns to that instant of revelation in the Addison Gallery, in which she imagines that her long-dead brother Bobby (another shadowy, though closer, sibling who became a Communist, rode a motorcycle, and took risks) would have understood the Edie-Andy phenomenon, even though he died just before it began. It is set up to be the “madeleine moment” that will clarify the meaning and purpose of the book. But, to me, what she presents is mostly a collection of musings. She makes some interesting, if fairly obvious, connections between the Factory era and contemporary social media, reality TV, and the WASPy old money fantasies marketed by (mostly Jewish) fashion designers like Ralph Lauren. She comments on the idea of self-invention and tries to correct a few media mischaracterizations (Edie was not a debutante or a Boston Brahman and she wasn’t really all that rich), but she leaves them largely undeveloped. Nothing quite gels. Wohl has a disturbing tendency throughout the book to back away from her points even as she makes them, as if afraid she will find herself trapped in some politically incorrect cul de sac or just a bad neighborhood.

She leaves other avenues unexplored — like America’s bizarre social class structure, with its bewildering codes and rules, within a supposedly egalitarian society, ground so richly exposed by novelists like Edith Wharton and John Cheever. Nor does she touch on the current status of “white privilege” or the growing realization that even the most respectable New England old money fortunes were founded on the expropriation of Native American lands, trade in products produced by slave labor, or natural resources stolen in colonized Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. She doesn’t step very far, either, into the ways in which Warhol’s art was driven by his own obsessions — beauty, money, sex, social status, fashion, image, and fame, which are also America’s obsessions. And this is a shame, because, despite all the books, including this one, there is much more about Andy and Edie that could be said.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 80 projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Tagged: Alice Sedgwick Wohl, Andy-Warhol, As It Turns Out: Thinking About Edie and Andy

Totally agree. And, by the way, I’ve a novel out now, published in Italy and soon in France , in which Edie Sedgwick’s story is the pretext for a well needed journey into the tumult of 1960s America. I hope that one of the American publishers who have already shown an interest will publish it: I would be curious and honoured by a review from you!

A book that fails to meet the reader’s expectations. Lots of insight as to family affluence, education and a lot of chest beating and name-dropping about the author, by the author. This is an exhaustingly boring and disjointed book. I would not suggest that anyone should waste their time reading.