Book Review: “Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld” — A Tale of Mobsters and Musicians

Guitarist Eddie Condon quotes a mobster on jazz: “It’s got guts and it don’t make you slobber.”

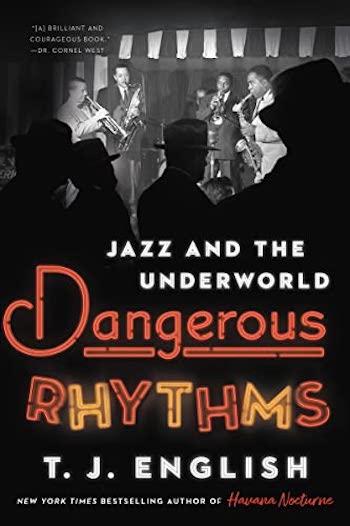

Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld by T.J. English. Harper Collins, 448 pages, $26.99.

If America had a 20th-century cultural id, two of its key elements would be jazz and the criminal underworld. The heart of the latter is vicious and greedy. The heart of jazz, if sometimes racist and sexist, can also be expressive and free. Yet the history of gangsters and jazz in America is ironically (and closely) entwined. The dance between them was always fraught, but they generated an energetic symbiosis that helped both survive and sometimes prosper, even if, on balance, jazz musicians drew the short straw.

If America had a 20th-century cultural id, two of its key elements would be jazz and the criminal underworld. The heart of the latter is vicious and greedy. The heart of jazz, if sometimes racist and sexist, can also be expressive and free. Yet the history of gangsters and jazz in America is ironically (and closely) entwined. The dance between them was always fraught, but they generated an energetic symbiosis that helped both survive and sometimes prosper, even if, on balance, jazz musicians drew the short straw.

If you want to write a book about the underworld, there’s not much of a paper trail — financial or journalistic. Most of the finances happened “off the books.” Media scrutiny was not just frowned upon — it drew harsh reprisals from tough guys. On top of that there was a lot of self-promotional mythologizing by those in and out of the arrangement, so what did get printed wasn’t necessarily credible. Add to this the fact that almost none of the principals are alive to be interviewed. Author T.J. English says that he relied on oral histories for much of his information, but that kind of testimony — even if it happens to be old — isn’t necessarily reliable. That said, there are other problems: factual contradictions, some stories seem underreported, and English’s style embraces a breezy “tell-all” glibness. Still, Dangerous Rhythms convincingly fleshes out the story.

English starts the story in the New Orleans area, with homemade instruments on plantations, “professors” playing piano in bordellos, and the rise of Storyville. He details the connection that grew between Sicilian immigrants, politicians, and Black and brown purveyors of the new style of music that came to be known as jazz. Some reading on crime in mid-19th-century American cities leads me to think that the link between music and the underworld was well established in the US before the “Black Hand” and mafia began to rule nightlife in New Orleans. In any city in the US, where public entertainment or gambling was available and alcohol served, criminal activity was likely to percolate. Ragtime, then jazz, happened to be the music that was drawing paying customers in New Orleans at the time when gangsters were establishing their hegemony. “Moral reformers” were happy to draw on this linkage between crime and jazz in an ongoing campaign against the new music.

Once criminal control was established — especially after the onset of Prohibition in 1919- — patterns became set. Crime thrived on a number of levels. Mobsters owned and ran the joints. Street toughs helped mobilize political and police cooperation through payoffs as well as delivering the vote for crooked politicians. Numbers runners spread the word about rent parties. Threats and violence were used when necessary, especially among gangsters trying to move up in the pecking order. It made no difference for musicians which gangster ended up on top. The system was universally seen as a “plantation.” Low-end rooms might be integrated — “black and tan” — but the large, classy, well-paying rooms were inevitably segregated. The tips could be large, but musicians served at the whim of the proprietors and were threatened or physically harmed if they wanted to move to another job (cf making Lena Horne stay at the Cotton Club). Or, if a gangster wanted a musician at his club, threats and violence were used to free them from their previous commitment (cf making Duke Ellington available for the Cotton Club). Anecdotally, a high percentage of jazz musicians carried weapons. (Pianist Mary Lou Williams’s disgust at the debased quality of the scene receives a lot of space in the book).

Louis Armstrong’s story runs throughout and, indeed, the trumpeter’s relationship with the underworld started early and proceeded until the end of his life. As a teen, he was nearly killed in gang crossfire. He recognizes early on that he needed a protector. Joe Glaser, tough guy, small-time criminal, and Capone associate, became that defender.

Running close behind the consideration given to Armstrong are the sagas of Glaser, Frank Sinatra, and Morris Levy. Sinatra had a lifelong infatuation with mobsters and occasionally used them as “muscle.” Levy was a gangster/tough guy with a fondness for jazz. He owned nightclubs, record labels, and music stores (Strawberries — remember that chain?). He elevated cutouts and bootlegs into high-yield operations. I was pleased to note that he was finally brought low by a combination of the US government and singer Betty Carter, who sued him for theft of her publishing rights and won.

Count Basie’s gambling habits placed him in an “indentured servitude” position with Morris Levy. However, it’s interesting to note that Dangerous Rhythms details no ongoing issues between gangsters and ’30s jazz stars other than Armstrong. Nothing here about Fletcher Henderson, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Bunny Berigan, Jack Teagarden, Chick Webb, Glenn Miller, Jimmy Lunceford or the Dorseys. (Tommy Dorsey does figure prominently in a sordid Sinatra episode.)

After WWII, vocals began to dominate the landscape and the performers most apt to deal with the mob were singers — the potential payoffs were greatest. Apart from Sinatra, stories of Vic Damone, Tony Bennett, and Bobby Darin are recounted. One nonvocalist in this section is bassist Charles Mingus. Although noted for his independence — he started Debut records with Max Roach — Mingus had Joe Glaser as his manager for a while. The story, like some in the book, does not feel complete. But English writes “Mingus admired Glaser’s tough-talking ways, but in the end … he felt he was being played for a fool.” Mingus later hired a more volatile gangster, Joey Gallo, to be his agent. He apparently realized the dangers involved with that choice and checked into Bellevue hospital, where he correctly assumed he’d have less of a chance of being killed by the Gallo brothers.

A Kansas City jazz club.

Kansas City rates a lot of ink. English sees it as the most illustrative example of how political-gangster-musical synergy can work. While Italian, Irish, and Jewish mobsters dominated, Black mobsters also play a role in this history. In Kansas City, there was Felix H. Payne and Piney Brown; in New York, Baron Wilkins and Caspar Holstein, who was “Boleta [numbers running] king of Harlem;” in Pittsburgh, William “Gus” Greenlee and Rufus “Sonnyman” Jackson. English rues the “glass ceiling” for Black mobsters. Because of racism, he notes, they didn’t have any access to white establishment power brokers. He often talks about Black gangsters investing in “community-based projects” — but he is never specific about what those projects were.

The criminal underworld continued to rule the jukebox industry, but the end of Prohibition was a blow to business. Some shifted focus to developing gambling outlets in Newport, Kentucky and Hot Springs, Arkansas. Las Vegas came a little later, along with Havana. In the late ’20s, to expedite bootleg rum-making, the mob forged molasses-importation relationships in Cuba. This led to the late ’20s opening of the Cuban Gardens nightclub in Kansas City (and some of the first exposure of Americans to Afro-Cuban music). Then, in the ’30s, the mob invested in Fulgencio Batista, who eventually became president of Cuba. Batista retired, a wealthy man, in 1944. He was encouraged to attempt a comeback in 1952 but it failed. However, he staged a coup and came back into power. Once established, he hired the mob’s main guy in Cuba, his old pal Meyer Lansky, as his “advisor on gambling reform.” Needless to say, the door to the mob was wide open. Havana became an international destination for gambling, sex (and music). The party only lasted a few years, however, until 1958, when Castro and his rebels took back control of the island.

Starting in the ’50s, after the demise of activity on 52nd St., mob interest in jazz waned. Drug-peddling aside, the nightclub business may simply not have been worth the effort and risk, aside from the most lucrative circumstances, like Las Vegas and the Copacabana in New York City. In the ’80s, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO) was mobilized, and the subsequent indictments and prison time set the mob back on its heels.

Apparently, Al Capone and other gangsters liked jazz. Guitarist Eddie Condon quotes a mobster saying, “It’s got guts and it don’t make you slobber.” More germane is the fact that jazz was the music that kept the cash flowing and that gangsters were always ready to resort to violence to make musicians do their bidding. Also, note how the mob understood that the best way to create a market for heroin in the US was to introduce it into the nightclub scene. As English says, “especially among a group they figured would be an easy sell: musicians.”

But, despite the criminal element, there was always an innate strength to the music, a core sustained and reinforced by individual genius, the interchange of ideas, and a competitive instinct among musicians. The inner life of jazz — its need to exist — served as a bulwark against the mayhem and venality of the industry in which it was forced to function. Had jazz not happened this way, it would have found another way to survive and thrive.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld, organized crime

Good review, but a question for the reviewer: does English make a case that there was anything more to the relationship between criminals and jazz musicians than gangsters making money? I’m not so sure jazz musicians were anything special. My own digging into this subject on the local scene leads me to think that musicians, stand-up comics, strippers–any entertainers–were just fuel for the money-making machine. “The customers like jazz this year? Then we’ll give ’em jazz.” So I’m just wondering how strong a case English makes for jazz being exceptional.

He doesn’t try to make a case for it, except for an occasional mention of criminals who actually liked the music. The “It’s got guts…” quote is pretty much a one-off.

However, there could certainly be a discussion about the relationship between the machismo pervading both groups

I just finished reading the book and find it disappointing because it has many errors of fact concerning jazz artists. Just for examples, English asserts with great confidence in more than one place that Thelonious Monk was a heroin addict. This is not correct. In his discussion of the Miles Davis album “Kind of Blue” English tells the reader that Wynton Kelly was the bassist (sic), rather than one of two pianists (the other being Bill Evans of course). I could go on, but the point is that a simple fact check would have caught these errors and could have been corrected without in any way diminishing the main arguments being presented in the text. Since that care was not taken to check facts, how do we the readers know what to make of so many parts of the narrative that are simply not generally known, not verifiable, and in some cases almost too sensational to believe. The case against Frank Sinatra stands out in this context in bold relief. The author diminishes his own credibility by his rush to publication and it leaves this reader scratching his head. It is really a shame because the errors are generally of little or no relevance to the main premise of the book and if they were removed there would be no question of the power main points. That the errors are there, however, indicates that the author is cavalier with the facts and as such which facts can be trusted? As it stands the book is not worth the powder.