Film Review: The 2022 Tribeca Film Festival — Where the Yellow Brick Road Leads to David Lynch

By David D’Arcy

The Tribeca Film Festival ends this weekend. As always, the documentaries at the festival were where you found the best films. Here are four that I can recommend.

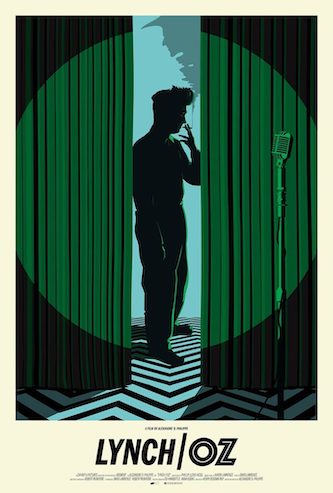

Let’s start with Lynch/Oz. David Lynch and The Wizard of Oz? This sounds like one of those cooking shows where a chef is given three improbable ingredients and asked to prepare a meal in two hours.

Let’s start with Lynch/Oz. David Lynch and The Wizard of Oz? This sounds like one of those cooking shows where a chef is given three improbable ingredients and asked to prepare a meal in two hours.

A joke?

Not so fast. This is the latest from Alexandre O. Philippe, the Swiss director who in 2017 gave us 78/52: Hitchcock’s Shower Scene, a chillingly meticulous dissection of the immortal sequence from Psycho in which the runaway secretary Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is stabbed to death by the innkeeper Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). The numbers in the film’s title represent the camera setups in the three-minute scene and the number of cuts Hitchcock made.

To call 78/52 the dissection of a scene would be an understatement. Autopsy might be a a better word — deconstruction in antiseptic black-and-white.

Lynch/Oz aims at grandeur and more than a little gentle mockery, raising the curtain on a host in exaggerated stage makeup, then leading us through almost two hours of scenes from the most popular film ever made — at least according to a scientific investigation conducted by Italian researchers. All the while, we hear arguments for Oz’s influence on Lynch’s films over five decades. Those arguments are provided by Amy Nicholson, John Waters, Karyn Kusama, and other filmmaker fans. No surprise, these speakers, whom you hear but don’t see, supply a lot about the influence of The Wizard of Oz on themselves. Waters is at his best here, eloquent and gossipy, speaking as a cinephile who makes movies.

Think of clicking red shoes, a laughing witch, the killing of another witch for which Dorothy is applauded rather than punished, an old man’s confession that, despite appearances of power, he’s really just an impostor behind a curtain (not a shower curtain this time), and a journey home that doesn’t seem headed there. Somehow all of this — and more, we should assume — is linked to the shady ambiguity of a director, Lynch, who is notorious for, among other things, never saying what any of his work means. Perfect for film critics who want Lynch’s work to be understood on their terms. I can only imagine what Philippe would have done with Fassbinder and The Wizard of Oz. OK. I’ve issued the challenge.

In 2019, Tribeca premiered another film in this vein of broad cinematic reconsideration with You Don’t Nomi, Jeffrey McHale’s reconsideration of Showgirls, Paul Verhoeven’s 1995 tale of a young woman seeking her fortune in Las Vegas. Scripted by Joe Eszterhas, the movie somehow became essential viewing for film nerds. Showgirls isn’t The Wizard of Oz for too many critics – although as a road movie leading to Las Vegas it might qualify for some. Reevaluating it 25 years later with a wiseass new generation (including women critics, sparsely represented in 1995) forced plenty of those who watched it again to reconsider their own judgments.

Lynch/Oz does that and more.

If the films of David Lynch draw on The Wizard of Oz, an unlikely sports documentary brought what looked like Lynch-inspired imagery to a profile of the tennis player John McEnroe.

Tribeca, to its credit, has led the way among festivals in screening films about sports, especially documentaries from ESPN’s 30 for 30 series. There is a crossover audience for these films, and that means there are real budgets for filmmakers. And there are some surprisingly effective results, such as the rapper Ice Cube’s doc on the L.A. Raiders and the swaggering culture that local hip-hop artists built around the team.

McEnroe, directed by Barney Douglas, dresses its star in a long black coat that seems lifted from a music video and sends him walking at night through the streets of New York. What were they thinking of? A search? For what? We’re not told why this voyage au bout de la ville was necessary, but there’s enough drama and irreverence between these long walks to make this film worth watching most of the time.

McEnroe was certainly worth watching when he played, win or lose. We see a lot of his complaining and yelling at officials and hear explanations long after the fact of how that tactic undermined the rhythm of a match and emboldened a frustrated perfectionist like McEnroe, who’s repentant about his brashness today. His matches were theater much of the time, theater that captivated the public and enraged his opponents. His whiny, boyish voice was as distinctive as any entertainer’s. It is toned down now that he earns his living talking about tennis at major tournaments.

Amid all the yelling, McEnroe the competitor is analyzed. Like Wayne Gretsky, he didn’t look like an athlete, and he lacked the muscle for today’s power game. But McEnroe’s merits were that he was relentless and smart, he seemed fearless, and he knew how to win most of the time.

The documentary focuses on friends and rivals, like the blond, charismatic Vitus Gerulaitis, who lost to McEnroe on the courts but led him into the New York nightlife and into playing music and, McEnroe admits, into drug use, which didn’t help his game. Gerulaitis died of carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty heater in the Hamptons in 1994. The film looks even more closely at Bjorn Borg, McEnroe’s polar opposite. The imperturbable and handsome Borg dominated tennis; his was the courtly image of the sport until McEnroe defeated him at the US Open in 1981. Then, at the age of 26, a shell-shocked Borg abandoned Grand Slam tennis for good. McEnroe, who never left the tennis world, still can’t understand that decision. Today, Borg comes off as mournful and lonely, but he speaks fondly of his younger rival. If you saw the feature Borg/McEnroe, this doc is a reality check.

There is a lot more to this McEnroe, but much seems left out. For example, there’s McEnroe’s troubled marriage to another celebrity, Tatum O’Neal. The doc has scenes of the couple battling photographers as well as running from them. By that point in the film, we have moved from an exciting, personality-driven tennis figure who is followed by a mass audience to an extended third act that McEnroe seems to want to manage. Maybe lawyers warned him not to give too many details. Today the bad boy is 63 and seems to have a wholesome family life with second wife Patty Smyth. If you’re curious about McEnroe’s art collecting and the gallery that he owned for a while, you’ll need to look somewhere else.

The long black coat? Every film needs a leitmotif.

McEnroe will air on Showtime in September.

A scene from A Story of Bones.

A Story of Bones takes us to a remote place, one of the most remote in the world, the island of St. Helena, pronounced Saint He-LEE-na. The island is 1160 miles west of South Africa, and 2000 miles east of Brazil. Served until recently by a weekly mail boat that made a six-day trip from Cape Town, it got its first airport a few years ago, built by the British government. Wind shears there keep large planes from landing.

St. Helena is where Napoleon, the most feared man in Europe, spent the last years of his life, dying there in 1821. The island commemorates his death every year.

The bones in the title refer to the remains of thousands of enslaved Africans buried in mass graves. The Africans arrived on ships that left from the continent with that human cargo. The skeletons are of captives who had died en route to St. Helena, on the first third of their Middle Passage to the Americas.

No one is sure how many were buried on the island. Around 10,000, estimates Annina van Neel, the environmental officer for St. Helena, who quit that job in order to organize an official burial. Because she was born in Namibia, she’s branded as an outsider by locals (who are called the Saints) for her activism. Compounding the island’s political and ethical dilemmas, the territory gets almost all its public funds from the UK government, and is overseen by an appointee from London. The colonial past isn’t past.

Filmmakers Joseph Curran and Dominic Aubrey de Vere watch the bureaucracy of this tiny island sputter and stall, even though van Allen finds international support for her project in the US. At the core of this powerful doc is the undeniable fact that everyone on the island is standing on a boneyard, on piles of evidence that the south Atlantic slave trade took a deadly toll even before enslaved captives were put to forced labor.

A Story of Bones opens as a truck’s mechanized shovel breaks through the ground. The camera cuts to a supervisor holding a bone that’s just been unearthed. “I think it’s human,” he says. Moments later, he’s brushing dirt off a skull near the surface. It turns out that more than 300 skeletons were removed from that site and placed near the island’s prison. They are still there, captives for life and afterlife.

This doc is built on two metaphors — one of a haunted island, another of colonial bumbling. Chunks of the island cover mass graves: the living (at least most of them) unknowingly walk atop the dead. While dead are left unburied, the UK government has just paid half a billion dollars for the island’s new airport, which is useless for anything but small planes because of dangerous wind shears. What we have here is an airborne twist on the “bridge to nowhere” theme. Could it be that providing the money to bury those remains with dignity would betray a secret that might threaten the island’s plans to develop a tourist industry? I smell a sequel here.

A scene from Sansón and Me.

Sansón and Me is the story of a young undocumented Mexican immigrant, Sansón Noe Andrade, who is serving a sentence in California of life without parole for murder. The filmmaker, Rodrigo Reyes, is another Mexican immigrant, the Spanish-language interpreter at Sansón’s trial. The film’s challenge is to reconstruct Sansón’s volatile life before a court locked him up.

The state of California refused to allow Reyes to film Sansón, on the grounds that bringing him that kind of attention would turn the prisoner into a celebrity. As an alternative, Sansón and Reyes expanded their regular practice of letter-writing — their correspondence grew to 900 pages — and cast the film with a former teacher from the boy’s hometown playing Sansón and with members of Sansón’s family in other roles.

The solution fits Reyes’s minimal budget. His research casts doubt on Sansón’s guilt as it exhumes the story of a poor family from a Mexican tourist town on the Pacific. As a child, Sansón moves from an orphanage in Mexico, and then to a series of immigrant jobs in the US. Then he is blamed for a killing that a relative committed. Think of the Book of Job on steroids.

Sansón and Me is a hybrid documentary, with characters played by people other than themselves. It is a narrative that shows the remarkable humility of its filmmaker and subject as it expands outward from a bare-boned outline of crime and punishment. The poignant story that emerges is of a rough life in Mexico that becomes even rougher north of the border. Since Sansón is undocumented in the US, the US government that he hid from does not play a role in his life until he’s locked up. He is left with nothing but his story to tell, and now this film. From Sansón’s letters, we learn that preserving his voice in writing keeps him alive, hopeful in a place where hope is scarce.

Sansón and Me will play on PBS next year.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: 2022 Tribeca Film Festival, A Story of Bones, Alexandre O. Philippe, Barney Douglas, David D'Arcy, LYNCH/OZ, McEnroe