Opera Album Review: The “Fidelio” Story a Year Before Beethoven’s Opera — and in Italian

By Ralph P. Locke

A new recording of Ferdinando Paër’s Leonora gives us characters we love (or love to hate) in a fresh light.

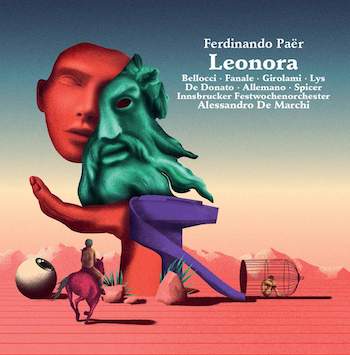

Ferdinando Paër: Leonora

Eleonora Bellocci (Leonora, disguised as “Fedele”), Marie Lys (Marcellina), Paolo Fanale (Florestano), Krešimir Špicer (Don Fernando), Carlo Allemano (Don Pizarro), Luigi de Donato (Giacchino), Renato Girolami (Rocco).

Innsbruck Festival, cond. Alessandro de Marchi.

CPO 555411-2 [2 CDs] 150 minutes.

Click here to order or to listen to any track.

Here’s a fascinating experience for opera lovers: a work first performed in 1804, a year before Beethoven’s Fidelio (1805, rev. 1806 and 1814), and using an Italian libretto that is based closely on the same French libretto that was the source for Beethoven’s opera. It’s Ferdinando Paër’s Leonora, first performed, not in Italy, but in Dresden (because Italian opera was so greatly loved there, as in other German-speaking cities).

Here’s a fascinating experience for opera lovers: a work first performed in 1804, a year before Beethoven’s Fidelio (1805, rev. 1806 and 1814), and using an Italian libretto that is based closely on the same French libretto that was the source for Beethoven’s opera. It’s Ferdinando Paër’s Leonora, first performed, not in Italy, but in Dresden (because Italian opera was so greatly loved there, as in other German-speaking cities).

Among other pleasant surprises, Jacquino, a character we know and love as a light-tenor role (because he’s a young lover), is here a bass-baritone (and equally comical). Perhaps more disconcerting, the villainous Don Pizarro is not a baritone but a tenor, putting him in the same vocal category as the opera’s male hero, Florestano. (I choose my words carefully because the plot also features a female hero: the title role, Leonora/Leonore.) The first time through, I kept feeling that the two characters Jacquino and Pizarro had traded places in the action; on rehearing, I began to feel the very different “rightness” of Paër’s choices.

But this is just the beginning of what one can learn from Paër’s Leonora. The work can be thought of as representing hundreds of well-crafted and potentially very involving operas that we tend not to know from the decades between repertory staples by Mozart (written in the years 1780-91) and major works of Rossini and Weber from the 1810s and ’20s.

True, many devoted operagoers and CD collectors are familiar with Cherubini’s Médée, though most often from the version with recitatives composed decades later by Franz Lachner, translated into Italian (as Medea), and made blazingly vivid by Callas. But other prominent opera composers of the day are, for most of us, merely names: Salieri, Spontini, Méhul, G. S. Mayr (Donizetti’s main teacher), and — today’s special guest — Ferdinando Paër.

Paër (1771-1839) is an obscure name to most music lovers. But recordings are beginning to help us. One can now get to know his opera Sofonisba (a recording of major excerpts, featuring Jennifer Larmore) and some sacred pieces and chamber music. As music historians have long known, Paër was one of the most successful composers of the day, turning out dozens of operas, especially — from one-act comedies to full-scale tragedies — for theaters throughout the Italian peninsula and also for Dresden and Paris. Like many of his contemporaries, he was often happy to use a plot, or even a specific libretto, that had been successfully set by others. Undaunted by Mozart, he composed a Marriage of Figaro and an Idomeneo.

Paër’s Leonora, as I said, was first performed in Dresden, a mere day’s ride from where Beethoven was living in Vienna. Composed and sung in Italian, it was the second in a string of four operas in an eight-year period (and in three different languages) to deal with the story of (to use their names from the first libretto) Léonore and Florestan, the husband whom, by great craftiness and bravery, Léonore saves from being murdered. The first opera to treat the tale was by the French composer and operatic tenor Pierre Gaveaux, entitled Léonore, ou l’Amour conjugal (1798); the third was by the aforementioned Mayr: L’amore coniugale (Padua, July 1805; in Italian, like the Paër). The fourth and last was of course Beethoven’s Fidelio (in German; like the Gaveaux, it has extensive spoken dialogue). The Gaveaux and the first version of Beethoven’s Fidelio (1805, without the massive changes made for 1806 and 1814) have been made available on DVD by Washington DC-based Opera Lafayette in productions that use the same sets and costumes as each other and even many of the same fine singers (click here for the Gaveaux and for the Beethoven).

A portrait of Ferdinando Paër. Photo:Wiki Common

Paër’s music here sounds a lot like Mozart, such as certain moments in Così fan tutte, though the similarities may be coincidental — the result of commonplace techniques — rather than conscious borrowings or allusions. More to the point, the music really works: the characters are limned effectively, and I was glad to see that this opera gives Marcellina and Giacchino (equivalent to Beethoven’s Marzelline and Jaquino) more of a chance to act and interact. Marcellina here is more directly involved in the events of Act 2, which also results in her getting more to sing. The musical numbers never outstay their welcome. Perhaps Paër learned this from Mozart, as Mozart learned it himself over the course of his career.

A compare-and-contrast of the four operas would provide a lifetime of fascination, plus of course there are the massive differences between Beethoven’s several versions of his own opera. (Traditionally, we call the two early versions Leonore in order to differentiate them from the 1814 Fidelio.) For one thing, Pizarro in Paër’s opera is a tenor, perhaps to emphasize his noble status, which he belies by his ignoble actions. The prison employee Giacchino is a comic bass-baritone, which causes him to resemble somewhat other operatic working-class figures such as Mozart’s Leporello, Masetto, and Figaro.

The singers are all spirited and accurate. Their voices may be smallish, but quite appropriate to their roles and to the size of the chamber orchestra that accompanies them and, as far as I can tell, to the hall in which they are performing. The recording was made during multiple performances in August 2020 (at a rather high point in the pandemic, amazingly). The staging was simple, consisting of rows of chairs, and the costuming was modern and plain, e.g., a white dress shirt (or a white T-shirt for the prisoner Florestano) and dark slacks. My favorite singer here is Marie Lys, who tosses off Marcellina’s coloratura passages with zest. She also winningly parries Giacchino’s unwelcome professions of love.

The recording comes with a libretto and two good essays, all decently translated. But errors abound: Pizarro is often misspelled Pizzarro (was the typist thinking about supper?), and, in the track list, Marcellina is listed one time as Marcello. Even more confusingly, Leonora is once listed as Pizarro. In a photo caption, tenor Carlo Allemanno (the Pizarro) becomes Carl. It should not be so hard to keep these things from happening. But, good news for noise-haters: applause has been removed.

A scene from the Innsbruck Festival’s semi-staged production of Ferdinando Paër’s Leonora. Photo: Innsbruck Festival

There was a previous recording, made in the late ’70s (in a studio) with magnificent singers (Ursula Koszut, Edita Gruberová, Siegfried Jerusalem, Wolfgang Brendel), under the expansive, phrase-shaping baton of Peter Maag. The 2013 reissue on Decca Eloquence includes a libretto and translation. So you can choose between the new, rather lithe and propulsive recording and the ’70s Maag, with its even more resonant acoustics and glorious vocals. Bit by bit, the dark era between Mozart and Rossini is coming into the light!

And I’m still trying to figure out if Marcellina and Giacchino seem a better match when he has a lower voice. Maybe he doesn’t sound like such an inexperienced kid? After all, the two do end up together, and when the singer of the Marcellina role is as strong as Marie Lys here, one may feel happy that she’s found a man of equal substance.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review is a lightly updated version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide, and is included here with that magazine’s kind permission.

Tagged: Alessandro de Marchi, CPO, Ferdinando Paër, Leonora