Book Review: “We Uyghurs Have No Say” — When Truth Telling Becomes Subversive

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

What do the words of an imprisoned Uyghur dissident tell us about the desperate plight of China’s ethnic minorities today?

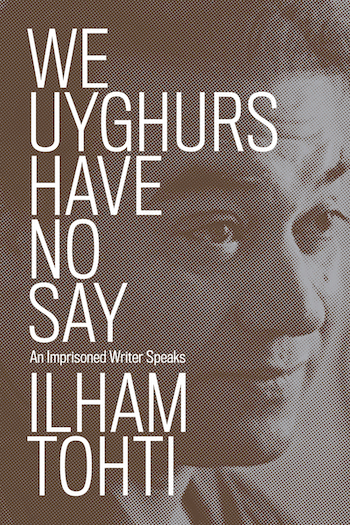

We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks by Ilham Tohti. Translated by Yaxue Cao, Cindy Carter, and Matthew Robertson. Verso Books, 192 pages, $24.95.

An ethnically Uyghur economist, writer, and public intellectual, Ilham Tohti co-founded Uyghur Online, a website designed to promote understanding between Uyghurs and Han Chinese. It is now blocked inside China. Tohti has been imprisoned since 2014; he was accused of the crime of advocating for “separatism” and espousing the violent overthrow of the Chinese government. Tohti was subjected to a two-day trial and was sentenced to life. Since 2017 he has been held incommunicado, with no access to his family or his lawyers. He won the 2014 PEN/Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award and the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought.

An ethnically Uyghur economist, writer, and public intellectual, Ilham Tohti co-founded Uyghur Online, a website designed to promote understanding between Uyghurs and Han Chinese. It is now blocked inside China. Tohti has been imprisoned since 2014; he was accused of the crime of advocating for “separatism” and espousing the violent overthrow of the Chinese government. Tohti was subjected to a two-day trial and was sentenced to life. Since 2017 he has been held incommunicado, with no access to his family or his lawyers. He won the 2014 PEN/Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award and the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought.

Human rights groups believe China has detained more than one million Uyghurs against their will over the past few years in a large network of what the state calls “re-education camps,” and sentenced hundreds of thousands to prison terms.

The Uyghurs are a Turkic people, and they are predominantly Muslim. Over the course of their long history, the Uyghurs have had to deal, often, with Russian and Chinese intervention. In 1884 their territory was known as East Turkistan when it was annexed by Qing China and renamed “Xinjiang” (“New Territory”), a name which it retains to this day. The People’s Liberation Army arrived in 1949, claiming to bring the Uyghurs into the “New China.” Promises of autonomy and equality were made but were never kept. The Uyghurs remained a problem, and now China has a solution: the full-scale eradication of the people and their culture.

In 2021, the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum reported that it was “gravely concerned that the Chinese government may be committing genocide against the Uyghurs.” Among the genocidal allegations leveled against the Chinese government: forced sterilization/abortion, slavery, sexual violence, torture, mass surveillance, separation of children and families, mass incarceration in “reeducation” camps, restricted freedom of movement, and much more. The response to these accusations, supported by reporting from the BBC, was a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Olympics and Beijing by the US, Canada, UK, India, Australia, and others.

Tohti’s book provides, for English readers, an indispensable firsthand description of the Uyghurs’ desperate plight. This collection of essays, articles, and interviews provides a clear overview of the beliefs (and heroism) of this so-called separatist. Ironically, it quickly becomes obvious that Tohti has no interest in separatism. In fact, he continually articulates a desire to build a bridge between Uyghurs and China’s dominant Han ethnic group. A member of the Communist Party (CCP), Tohti offers suggestions to the Chinese state about how to empower unification. He often returns to a key point: his belief, shared by other Chinese intellectuals such as Ma Rong, that China must reject its now obsolete ethnic policies (inherited from the Soviet Union) and embrace an approach that works for modern-day China. He draws on Chinese law as well as real-world knowledge about his people to make his case. Tohti continually returns to the goals of the CCP: he asks for a more just implementation of principles that are already on the books. The changes he requests are practical moves that simply acknowledge China’s ethnic reality. He underlines his political goals again and again. They are, in essence, the same goals espoused by the Chinese state: “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Tohti’s contention is that the Uyghur Autonomous Region established in Xinjiang was never, in effect, Uyghur or autonomous. As Han migrants and their institutions arrived, Uyghurs lost any chance of exercising control over their lands. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, while billed as an economic development enterprise, functioned more as a paramilitary group designed to divest Uyghurs of their resources. Once the Han population in the capital, Ürümqi, achieved a three-quarters majority, Indigenous Uyghurs were restricted to living in veritable ghettos on their own land. Tohti notes that “Xinjiang is the only place in the world where local university graduates have a lower status than migrant farmers.”

Tohti began warning China about this crisis for the Uyghurs as early as 2005: “The core problem is not that the vast majority of Uyghurs want independence. Only a very small minority believe that Xinjiang independence is the only way to solve the problem. Most Uyghurs accept China’s sovereignty over Xinjiang; they simply seek a truly meaningful kind of autonomy.” The Chinese government has reacted with hostility to Tohti’s warnings and advice.

Imprisoned Uyghur writer Ilham Tohti. Photo: Amnesty Internationa.

How did it come to this? In 2001, in the wake of September 11th, China and Russia signed the “Shanghai Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism.” The agreement was convenient for Russia; the Chechnya conflict had entered a new guerilla phase led by pro-Russian Chechens. There was now legal clout behind the assertion that the separatists’ “holy war” was not about independence — it was about religious extremism, terrorism, and separatism. These “three forces” (三个势力) became part of China’s official policy in Xinjiang, as well. Any claims for independence were classified as “separatism,” guerilla wars were “terrorism,” and the religious language that challenged political secularism was “religious extremism.” Tohti’s treatment should dispel any doubt that this linguistic power play was done in bad faith. Tohti studiously avoided advocating separatism; instead, he wrote that “the natural merging of ethnicities and the creation of societies in which diverse ethnic cultures can coexist and learn from one another is an unstoppable historical trend that no one will really oppose.” Tohti reasonably places the responsibility for unification on the government: “The reality is that China is ruled by the Han. So they should bear some responsibility for this country and for our fate. You’re the ones who have made us integrate. You’re leading us, and as leaders you must take responsibility and be inclusive and tolerant. If 1.3 billion Han cannot tolerate 10 million Uyghurs, then how can you talk about unity or harmony?”

Regarding religious extremism, Tohti again points to the Chinese government as helping to create the situation it condemns:

We once had our own perfectly good system of clothing, culinary culture, and music. Why are these now all becoming increasingly Islamicized? It’s because ordinary people have lost all hope in their government, in society, in Uyghur intellectuals, and in secularism. The government was first to destroy the forces of secularism. These should have been most able to interact with Han society and the government, but the government destroyed them instead. So Uyghur society has moved in a completely different direction and become distorted.

Tohti’s “crime” is that he took his government and the CCP at their own word. “Chinese law clearly states that ethnic autonomy is a fundamental state institution,” he argues, citing the 1982 Constitution and the 1984 Regional Autonomy Law. “Members of ethnic minorities may hold key positions in local administrative bodies,” he insists. “They have the right to preserve their own folkways and customs and enjoy religious freedom. They have the right to use their ethnic languages to develop schools of all levels and types and the government has the responsibility to establish ethnic schools.”

Why would the Chinese state persecute an intellectual for insisting that the government uphold and implement its existing laws? For making suggestions in policies that would curtail division and the inevitable growth of fundamentalism and violence? Tohti concludes that “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” the guiding principle of the New China, has gradually morphed into “totalitarian ethnonationalism.” Was there ever any genuine intention to fight the “three evils”? The Han-dominated state’s interest in uncovering seditious activities — separatism, terrorism, and religious extremism — made it easier to eradicate other ethnic groups. “Han people,” Tohti declares, “need to reflect more on their own nationalist and fascist attitudes. Over the past twenty years, Han people — especially the younger generation — have grown up drinking the wolf’s milk of nationalism. They are very emotional and angry, and their chauvinism is quite serious. To put it bluntly, some in Han society have turned fascist against us.”

The absurdity of the treatment of the Uyghurs is astounding. The New China was founded on the idea of rejecting a “century of humiliation” (百年国耻) rooted in the ravages of colonialism. The Chinese government seems to be more than willing to repeat the mistakes of the past. Ironically, the official ethnic policies of China claim that “the patriotic spirit formed during the fight against foreign invasions in modern times is the political basis for practicing regional autonomy for ethnic minorities.” What this means in practice today, however, is that any dissent coming from ethnic minorities is treated as opening the door to foreign aggressors. The logic, as Tohti notes, is fascist, and that explains why this brave man has been placed in prison — he is a truth-teller, not a separatist. He points out the hypocrisy of the Chinese government: perceptions of national humiliation are blamed on the “corrupting” influence of minorities whose inferiority and subversiveness are the projections of a majority looking for enemies to bond against.

Tohti no doubt knew that the state would silence him. But the words in We Uyghurs Have No Say contradict the volume’s sober title. His writing serves as a warning about atrocities to come — we will do well to heed it.

For more information please visit the Uyghur Human Rights Project and End Uyghur Forced Labor.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: China, Ilham Tohti, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Uyghur, Verso Books