Book Review: From Rome in 63 BCE — A Warning for Our Perilous Political Moment

By Emily Katz Anhalt

This most timely new translation of Sallust’s The War Against Catiline describes the ancient version of a phenomenon we will recognize instantly: a cold-blooded grift transmuted into terrorism posing as patriotism.

How to Stop a Conspiracy: An Ancient Guide to Saving a Republic by Sallust. Translated with commentary by Josiah Osgood. Princeton University Press, 240 pages, $16.95.

The losing candidate in an election for the highest political office in the republic conspires with well-placed associates and rallies his ravening followers to destroy the system that denied him victory. Born to great privilege, this unprincipled man of unrestrained appetites and impulses draws support from all ranks: other aggrieved privileged elites as well as disaffected ordinary citizens. He comes perilously close to destroying a centuries-old republican political system and usurping executive power.

The place and time? Rome, 63 BCE.

As details of the long-prepared and still ongoing conspiracy to overturn the results of the 2020 U.S. Presidential election continue to emerge, the conspiracy of L. Sergius Catilina (“Catiline” in English) in 63 BCE offers a vital cautionary warning for our own volatile and perilous political moment. Josiah Osgood, Professor of Classics at Georgetown University and specialist in the history of the late Roman Republic, has produced a most timely new translation of The War Against Catiline (Sallust’s Bellum Catilinae). Writing in the late 40s BCE, the Roman historian Sallust (c. 86-35 BCE) describes a prominent nobleman’s efforts to overthrow the nearly 450-year-old Roman Republic and install himself as dictator. Osgood’s engaging English version enlists Sallust’s treatise in the struggle to preserve and strengthen the laws, institutions, and norms of any democratic republic.

In a comprehensive but concise introduction, Osgood situates Sallust’s account of Catiline’s conspiracy not only in its own historical context but also in the history of the U. S. Republic. Osgood notes the presence of political conspiracy theories in America from the 18th century to the present day, some reflecting anxiety or paranoia, others identifying real conspiracies. Acknowledging that conspiracy theories can be manufactured without evidence for political gain, Osgood argues persuasively that Sallust’s account exposes the real threat that an actual conspiracy poses for a republic; even a failed conspiracy can spark civil war.

Catiline exemplifies any ambitious and cynical political leader eager to exploit economic and political inequities and animosities for his own benefit at the expense of everyone else. Osgood explains that, “for all the honorable pretexts of ‘defending the rights of people’ or ‘keeping the influence of the Senate supreme,’ the politics of his [Sallust’s] day was at heart a naked struggle for individual power. Everyone claimed to be acting for the ‘common good’; nobody actually cared about it.”

Osgood admirably rejects the tendency among modern historians to discount the influence of individuals on human events, asking, “Does anyone really think that the character of politicians and citizens has no impact on public life?”. Catiline was charismatic, treacherous, and broadly popular with the discontented and economically desperate at all levels of Roman society. Observing the Founders’ sensitivity to the potency of individual character, Osgood recalls Alexander Hamilton in 1800 dismissing Aaron Burr as a greedy, ruthless, opportunist by calling him “the Catiline of America.”

A statue of Sallust

The defeat of Catiline required careful evidence-gathering, courage, ingenuity – and military might. Having lost to M. Tullius Cicero in the elections of 64 BCE for one of two consulships for the following year, Catiline plotted secretly with supporters inside and outside Rome to slaughter the Republic’s current political leaders and set the city ablaze. (Instead of one President, the Roman Republic had two annually-elected executives, called consuls.) Though from a prominent aristocratic family, whereas – humiliatingly for Catiline – Cicero was not, Catiline was deeply in debt, needing the wealth that he could extract from the provincial governorship that would follow a year as consul. Sallust details Cicero’s dramatic capture and exposure of five prominent conspirators, a debate in the Senate regarding the conspirators’ fate, their summary execution, the subsequent military defeat of Catiline’s two legions, and Catiline’s death in battle. “When a genuine conspiracy does arrive,” Osgood concludes, “we need leaders brave enough and clever enough to face up to it and defeat it, while also taking into account the long-term consequences of their actions.”

Historians always want their work to be relevant – but perhaps not quite so much. Sallust describes the ancient version of a phenomenon we recognize: a cold-blooded grift transmuted into terrorism posing as patriotism. Denouncing his dissolute, polarized, and increasingly violent contemporaries, Sallust condemns the material greed, corruption, and lack of self-restraint of powerful men and their growing “desire for illicit sex, gluttony, and other self-indulgence.” He identifies Catiline as an entitled, dishonest, traitorous leader whose mind is “shameless, cunning, versatile – able to pretend or dissemble anything at all.” Seeking self-enrichment, this would-be autocrat cloaks his greed, rapacity, and cruelty in cynical claims of freedom and justice, characterizing his assault on the Republic as “a most splendid and glorious enterprise” aimed at restoring his followers’ freedom, wealth, honor and glory.

Catiline’s popularity exemplifies both the enduring appeal of a charismatic, manipulative, lawless, leader and the appeal of conspiracies more generally. Then as now, the angry and desperate not infrequently prefer to situate their own personal failures in the context of a larger, noble cause, reinventing themselves as part of a glorious movement. Catiline was adept at identifying men who would be susceptible to his enticements. A criminal and sexual predator himself, unrestrained by law or custom – possibly even the murderer of his own adult stepson – Catiline appealed to the dissolute and depraved, encouraging their debauchery and criminality. Attracted to the chaos that Catiline offered, his followers “preferred uncertainty over certainty, war rather than peace.” Though pleading poverty and debt as motivation, Catiline’s supporters claimed to seek not power or wealth but freedom and the legal protections of law. The conspiracy – essentially a terrorist plot, including extensive preparations for targeted assassinations and arson throughout the city – initially remained widely popular. “Such was the intensity of the disease,” writes Sallust, “that, like a plague, had attacked the souls of many citizens.”

Emphasizing the degeneracy of Catiline and his followers, Sallust depicts Rome’s prior history as a glorious age of ethical and political purity that never was. In fact, efforts to ameliorate, via land reform and other measures, serious economic inequities between the wealthy few and the impoverished masses had led not infrequently to bloodshed, particularly since 133 BCE. By the late Republic, unrestrained competition for wealth, status, and power had become a blood sport, as ruthless, powerful elites sought colossal financial and political rewards. Initially, some ambitious political leaders may have been sincere reformers, others – like Catiline – not so much.

Catiline meets with his co-conspirators, from a medieval French book of Roman history.

Sallust’s account reminds us that facts matter in combating conspiracies. Unlike a fact-free allegation of conspiracy corroborated only by the complete absence of evidence, real evidence distinguishes a real conspiracy. Although Catiline’s defeat ultimately required not words but swords, objective evidence proved vital. Impassioned speeches by Cicero in the Senate and also directly to the Roman people could not deter Catiline, but Cicero’s painstaking accumulation and articulation of factual evidence forced sympathizers into declaring openly if they were commited to violent insurrection or to the stability of the current system. Had Cicero not gathered the evidence to expose the conspiracy, the attack would have come as a surprise from within Rome. Indisputable evidence compelled Catiline and his supporters to leave the city and unified Romans to mount a military defense against an existential threat from outside.

Catiline’s defeat illustrates not only the value of evidence but also the fragility of the rule of law. Roman laws protected citizens from summary execution. The Senate’s decision to execute the five captured conspirators suggests that a violation of law cannot slow the erosion of the rule of law. In the contentious debate regarding the conspirators’ punishment, Julius Caesar urges not clemency but restraint. (Yes, that Caesar, Rome’s future dictator.) Caesar recognizes, presciently, that executing Roman citizens without trial will set a terrible precedent. Nevertheless, the Senate recommends execution, and the consul (Cicero) complies. Sallust presents Cicero’s action, though illegal, as necessary and effective, at least in the short run. By unilaterally declaring the conspirators to have forfeited their citizenship rights by their actions, Cicero may have thwarted this particular conspiracy, but he fails to slow the Republic’s descent into lawlessness, civil war, and finally autocracy. In a painfully ironic coincidence, Rome’s first emperor (Augustus) was reportedly born on the very day of the Senate’s debate regarding the fate of the Catilinarian conspirators (Suetonius, Divus Augustus 94). Rather than bolstering the rule of law, Cicero’s illegal killing of Roman citizens merely foreshadowed future illegality and slaughter.

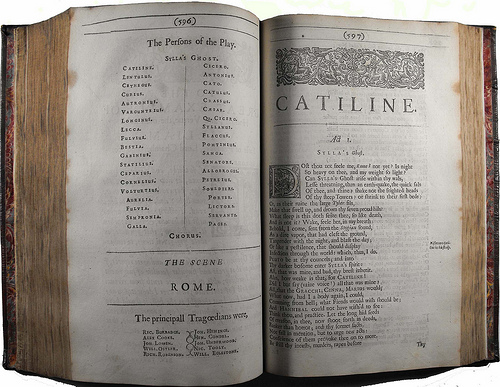

A copy of Ben Jonson’s 1611 tragedy Catiline, based on Sallust’s history. See the Art Fuse editor’s comment below.

The conspiracy of Catiline highlights the danger that political violence and intimidation pose to communal welfare and stability. Widespread support for Catiline imperiled the Republic’s survival. The Romans were discovering, as we are, that institutional protections against abuses of power –though necessary – are not sufficient. Now, as then, economic inequality and political discord provide both incentives and noble-sounding pretexts for violence. Our modern democratic republic offers the possibility of peaceful political succession and nonviolent policy change. But Sallust reminds us that attitudes, not institutions, constitute our best defense against conspiracy. Protection against sedition resides in the integrity, restraint, and foresight of political office-holders and ordinary citizens. Crucially, Sallust demonstrates the impossibility of attempting to preserve the rule of law by violating it. Violations of law undermine republican norms and institutions. Once introduced into the political process, violence and illegality will escalate. Illegal violence precipitates more violence, providing the very chaos necessary for an autocrat’s successful power grab.

Analogies are useful not only for the parallels they reveal but also the distinctions. A debt crisis in Italy, dysfunction in the Senate, and great material rewards for victory combined in 63 BCE to offer the perfect opportunity for conspiracy. But the Roman Republic was never remotely democratic, egalitarian, or humane, and neither Catiline nor his opponents sought to make it more equitable and just. While laudably preferring a republican system to the rule of an unaccountable autocrat, Catiline’s opponents sought to preserve a deeply iniquitous system. The Romans never found the recipe for combining individual freedom with equality and political stability. Rome’s experience in the late Republic cautions us against preserving inequities even as we seek to preserve the rule of law.

Osgood’s clear, engaging translation of Sallust’s The War Against Catiline brings vital aid from the past to the present. (Happily for readers, Osgood transmits Sallust faithfully while taming Sallust’s challenging, abrupt prose style and avoiding the archaisms and asymmetries of the Latin text.) In ancient Rome, unscrupulous ambition and cynical disregard for the public welfare produced decades of horrific internal conflict – Romans slaughtering Romans in orgies of proscriptions and civil war. A generation after Catiline, the Republic devolved into a military dictatorship. Once securely in power, Rome’s first emperor showed some restraint and public beneficence. But few of his successors in ancient Rome, or autocrats anywhere throughout history, have shown much concern for the welfare of the peoples they rule. Since violent conspiracies fail to produce egalitarian, humane, or healthy communities or politics, Sallust demonstrates not only how to stop a conspiracy but also why.

Emily Katz Anhalt teaches Classical languages and literature at Sarah Lawrence College. She is the author of Enraged: Why Violent Times Need Ancient Greek Myths (Yale University Press, 2017) and Embattled: How Ancient Greek Myths Empower Us to Resist Tyranny (Stanford University Press, 2021).

Tagged: Catiline, Emily Katz Anhalt, How to Stop a Conspiracy

Back in 2011 I commemorated the 400th anniversary of Ben Jonson’s second tragedy, Catiline: His Conspiracy. It failed in its initial production and has been rarely (if ever) revived since then, which is a shame. Yes, Jonson lets Cicero talk and talk and talk and talk … but with some determined cutting this would be a fascinating play to stage today. Emily Katz Anhalt makes its uncanny relevance clear in her review of a new translation of Sallust’s chronicle of Catiline’s crimes, pointing out their resonances with Trump’s anti-democratic con job.

Do we need another Julius Caesar? No, we don’t. Is there a theater company in America with the courage to take on Jonson’s powerful study of political gangsterism? Perhaps a university theater troupe? New York’s Red Bull Theater, my hopeful eyes turn to you.

Given the ongoing catastrophe in Ukraine, here is a bit of hyperbolic poetry (from a conspirator) in Catiline that reflects the mad inhumanity of Putin:

Swim to my ends, through bloud; or build a bridge

of carcasses; make on, upon the heads

Of men, strooke down, like piles; to reach the lives

Of those remaine, and stand.