Film Reviews: Three Nervy Indies at the Boston Sci-Fi Film Festival

By Eva Rosenfeld

A trio of independent movies draw on sci-fi to explore the nooks and crannies of creativity.

At the Boston SciFi Film Festival: Alien on Stage, New England premiere; Elulu, US premiere, virtual release; Alchemy of the Spirit, East Coast premiere.

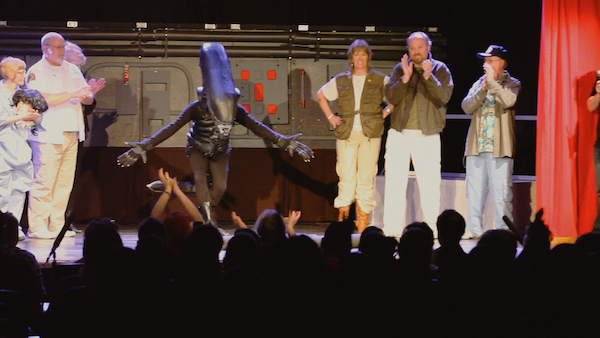

The “Alien” takes a bow in a scene from the documentary Alien on Stage. Photo: Boston Sci-Fi Film Festival

“Having an interest outside of work is vital for your, sort of, health and well-being,” says a communications manager for the Wilts and Dorset Bus Company near the beginning of the documentary Alien on Stage. This nugget of halfhearted corporate-speak turns out to be truer than you would think in this festival standout. The film follows a group of Dorset, UK, bus drivers as they attempt to produce a stage play adaptation of Ridley Scott’s 1979 sci-fi classic Alien.

Luc, an aspiring screenwriter, is fed up with the standard Christmastime “pantomime,” a British tradition of folky musical slapstick, and decides to adapt the script of Alien instead. Luc’s girlfriend Amy makes costumes, his grandfather builds the sets, and mom Lydia is cast as a deadpan Ripley, the heroine Sigourney Weaver plays in the original. Pete, a sheepish night shift supervisor, takes internet tutorials, fastens insulation piping, and rigs fishing poles. The end result is an impressive Alien. Despite receiving little support and expecting no reward, the crew take up new creative tasks and perform them with ingenuity and flair.

Alas, at first all their creative labor is barely recognized. The crew expects opening night to sell out, but it draws barely 20 people. “We haven’t really had any feedback, to be honest, from people. Nobody’s really said anything to any of us,” one cast member reflects, sitting on one of the company’s buses.

The neglect changes with the intervention of two Londoners — directors Danielle Kummer and Lucy Harvey — who discover the production by chance (a glimpse of a poster) and imagine bringing the show to London, perhaps to a working men’s club. To the bewilderment of all, with the support of a theater manager who also used to drive a bus, the cast members find themselves performing at Leicester Square Theater in London’s West End. Kummer and Harvey’s decision to make a film about the experience is driven by their enthusiasm for the play. Their first feature documentary, it is a nimble and funny rookie effort, devoting ample screen time to the personalities and creativity of the bus crew. Thankfully, we also get to see a generous slice of the show, which has been invited back to the West End Theater for an annual performance.

The joy of Alien on Stage lies in watching the protagonists struggle to create something stageworthy, and then see them attempt to conceal their giddiness at achieving something more: a life-affirming work that brings lasting satisfaction to the crew, the audience, and now to viewers.

A scene from Elulu. Photo: Boston Sci-Fi Film Festival

The animated film Elulu is set in a soft-edged world full of cats, bugs, and trees. After his mother dies, a son returns to his family home. Very little dialogue is provided, aside from some rudimentary phrases that flash on the guy’s computer screen: “UNEMPLOYED SCIENTISTS.COM”; “CERN VALIDATES SUPERSTRINGS THEORY!!”; “FUNDING FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ORIGINAL IDEA.” That is about all we get as explanation for the events that follow. We see imaginary creatures — with the ability to transverse dimensions — guide mother and son through alternative realities. In some of these worlds, the mother lives on, allowing the pair to revisit closely held memories. The theoretical physics premise stays well in the background of what turns out to be an emotional (and often wordless) exploration of loss.

Elulu was made, says filmmaker Gabriel Verdugo Soto, “mainly with the power of my will.” He hand-drew the footage over eight years, in his hometown of Santiago, Chile, using only free and open-source software. The lush animation style emphasizes movement and rhythm, which is enlivened by Soto’s original score. Like one of his heroes, animator Hayao Miyazaki, Soto exploits pauses and in-between moments to enhance the film’s emotional power. Miyazaki has criticized the “mass production” style of much contemporary animation, and Soto is a heroic example of a noncommercial one-man studio. Soto’s film blog details years of tedium, setbacks, and breakthroughs. Completing the project was a perpetual uncertainty. The result is a unique film that feels both personal and enormously loving.

A scene from Alchemy of the Spirit. Photo: Boston Sci-Fi Film Festival

From veteran independent filmmaker Steve Balderson comes Alchemy of the Spirit. Like Elulu, this film features a largely nonverbal story line about the complexities of mourning. Artist Oliver Black continues to see his recently deceased wife, Evelyn, in their shared home. From the vantage point of death, she offers Black glimpses of a heightened field of perception. The cinematography conveys this unreal vision through visual disruptions: veils, reflections, glaring light, a slippery sense of time. The colors — blues and yellows — are hypersaturated, as if Argento’s Suspiria were set in the daytime.

The effect is to make the product of grief — an intensification of sensory and aesthetic awareness — concrete. Black grieves his wife, but he also revels in the artistic possibilities of what he is experiencing. With her encouragement, he gets to work on some paintings. Unfortunately, the ghostly premise falls short when it comes to the character of Evelyn, who is relegated to the status of wife and muse. This wife from the beyond exists for the sole purpose of selflessly encouraging her husband’s creativity.

What Alchemy does particularly well is to lay bare what can blight making art. Black and his wife are interrupted by the artist’s sycophantic agent, who continually wants to know whether or not his work has been completed. In private, Black and Evelyn discuss the beauty of life and the universe with ease. Those sentiments sound clunky and trite when Black struggles to explain his work to a wealthy patron. Like grief, Balderson suggests, creativity demands privacy.

Eva Rosenfeld is a writer and artist from Michigan based in Cambridge, MA.

Tagged: Alchemy of the Spirit, Alien on Stage, Boston SciFi Film Festival, Danielle Kummer, Elulu, Eva Rosenfeld, Gabriel Verdugo Soto, Lucy Harvey