Visual Arts Review: “America’s Past-time” — Are We Having Fun Yet?

By Chloe Pingeon

The strength of Robert Freeman’s Black figures, even as they endure humiliation or violence, remains a prominent element in his vision.

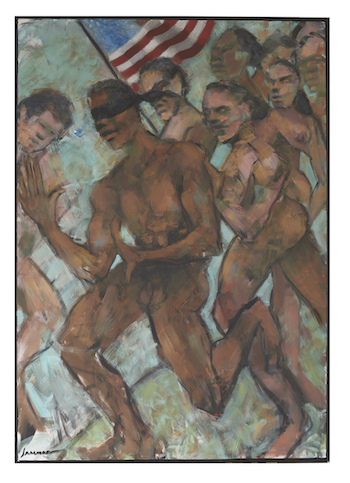

Robert Freeman, Blind Man’s Bluff, 2021. Oil on canvas. Photo: courtesy of the artist

To understand Robert Freeman’s works in America’s Past-time (on view at Childs Gallery through March 14), one must first understand the stark contrast between his art today and in the past. As an artist, Freeman has until recently tended to lean into the celebratory. His large-scale oil paintings presented strong Black figures in vivid colors and vibrant scenes. His work drew on personal experience and conveyed an encouraging social message: Freeman portrayed the power and elegance of the Black middle class.

On entering Childs Gallery, I was struck by how forcefully Freeman’s paintings fill the display space. Black figures dominate the canvases, blurs of color swirl and curl through dramatic scenes. At first glance, Freeman seems to be doing what he has always done: capturing beauty, capturing Black humanity, celebrating the joy of the Black middle class. Here, on what has traditionally been one of the most exclusive streets in Boston, Freeman is making his usual blazing statement for the value of Black lives. Now, though, it includes a passionate undercurrent of sadness because of the brutality and violence — still targeted at Black Americans — that has become impossible to ignore.

At a virtual artist’s talk for Child’s Gallery, Freeman explained that he “never used to talk about [his] paintings. I didn’t think artists were responsible for our paintings. I thought we tapped into a jet stream of energy and that creativity flowed through us and onto the canvas and we weren’t responsible for the work. I don’t believe that at all anymore.” America’s Past-time reflects Freeman’s sensitivity to the present, which has meant a departure from his assertion of Black accomplishment. This solo exhibition displays a poignant awareness of current events — there is outrage and sadness here, though it comes with an intriguing touch of irony. The figures in his paintings are engaged in children’s games — a nod toward the painter’s earlier jubilance. But the games have become deadly. Losers meet violent ends. Violence lurks behind bright colors and playful titles. Shaken by police brutality and the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black Americans, Freeman wants to draw attention to a broken system, to the running of rigged games. By focusing on old pastimes (Blind Man’s Bluff, Capture the Flag), the artist nimbly underlines that today’s inequality and injustice are not new.

Robert Freeman, Capture the Flag, 2021. Oil on canvas. Photo: courtesy of the artist

When I enter the gallery I first notice American Regatta, which depicts boats in shades of tan and darker brown churning in a blue-green sea. On a closer glance, I notice that the boats are colliding with each other. They are overturned or pitched vertically into a disorienting fracas of color that may represent either sky or sea. So much is unclear: the orientation of the ships, the positioning of the regatta’s participants, who the figures are who are being senselessly thrown about. This regatta has clearly gone awry. Are these boats slave ships? In the large rectangular Capture the Flag, two figures, a boy and a girl, fill the bottom half of the frame. Their skin is pale and their hands are raised in victory as they grasp for a volleyball colored like the American flag. Above them, a Black figure clings to the flailing arm of another figure. They have lost the game, and they might be in danger of being crushed by a wave that is filling the top of the canvas. A boat sporting an American flag rides a wave above the game players. It seems to be marking its territory. The Black man reaching for the hand of another is striking. A sign of humanity amid the all-American competition? They have been defeated — but are they giving up?

The strength of his Black figures, even as they endure humiliation or violence, remains a prominent element in Freeman’s vision. In Blind Man’s Bluff, a blindfolded Black man is being chased by an angry mob through a pastel blue and green background. The man’s facial features are far more prominent than those who are chasing him, even as they gain ground. His humanity is asserted. The white mob, expressed via a sort of collective fuzziness, holds an American flag.

The question, then, is where does a game’s entertainment end and real-life punishment begin? When does one group’s desire for harmless fun end up terrorizing other human being? When does a system play a game whose primary purpose is to utterly demolish individual integrity? Comparing reality to a game gone wrong has become a common trope in popular art. For example, take the mega-hit series Squid Games (which Freeman says he had not seen while he worked on the paintings in his exhibition). But tropes do not rise out of thin air, and there is an awareness that rigged economic systems (as evidenced by the growing disparity between rich and poor) have been designed to play games with people’s lives. This suspicion is generating an enormous amount of anger, and Freeman is tapping into that outrage. America’s Past-time seems to be asking what is becoming an increasingly pointed question — are we having fun yet?

Chloe Pingeon is an arts and culture writer currently studying journalism and film at Boston College. You can find her on Twitter @chloepingeon