Opera Review: “Iris,” A Powerful Vision of an Imaginary Japan — Six Years Before “Madama Butterfly”

By Ralph P. Locke

The composer of Cavalleria rusticana brought his sense for characterization and drama to the all-too-plausible tale of a woman victimized by a cad.

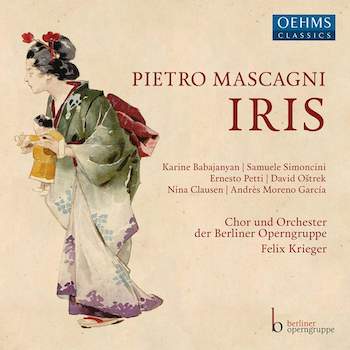

Pietro Mascagni: Iris (1898)

Karine Babajanyan (Iris), Nina Clausen (A Geisha), Samuele Simoncini (Osaka), Ernesto Petti (Kyoto), David Ostrek (Blind Man).

Berlin Opera Group Chorus and Orchestra, cond. Felix Krieger.

Oehms [2-CD] 119 minutes

Click here to purchase or to listen to the beginning of any track.

The “Berliner Operngruppe” was founded in 2010 for the purpose of bringing back to performance, in concert or in semi-staged versions, operas that have been relatively forgotten, such as Donizetti’s Betly (freely based on a Goethe play about love in a village) and Verdi’s Stiffelio (an attack on smug societal attitudes toward supposed sexual “purity”). Performances take place in the Berlin Konzerthaus.

The “Berliner Operngruppe” was founded in 2010 for the purpose of bringing back to performance, in concert or in semi-staged versions, operas that have been relatively forgotten, such as Donizetti’s Betly (freely based on a Goethe play about love in a village) and Verdi’s Stiffelio (an attack on smug societal attitudes toward supposed sexual “purity”). Performances take place in the Berlin Konzerthaus.

The present recording of Pietro Mascagni’s much-admired opera Iris (first performed in 1898) was made at a single performance in February 2020, just before the pandemic shuttered nearly all concert halls worldwide. The performance was the opera’s first ever in Berlin. It was given without sets and with just a few costumes (for the play-within-a-play). In compensation, for us at-home listeners, the booklet shares wonderful set and costume designs from the 1898 world premiere (in Rome). Thus we can imagine how the work might feel in a full production.

Iris is the seventh of Mascagni’s 15 operas. Cavalleria rusticana was his first; L’amico Fritz, his second. It is renowned as being one of the few major operas to be set in Japan. Puccini’s Madama Butterfly would follow in 1904: at first a failure, but soon a triumph across Italy and around the world.

Mascagni’s heroine bears some similarity to the Japanese female protagonist in Messager’s enormously effective Madame Chrysanthème (1890) and the one in Puccini’s Madama Butterly: for instance, she is beautiful and passionate, and is repeatedly compared to elements in nature — in this case to the sweet-smelling flower whose name she bears. The name is also symbolic of another kind of “iris,” for she functions as the eyes for her father, known in the libretto simply as Il cieco (The Blind Man). This particular connection, too, was echoed in a later Puccini work: in Turandot Liù guides her father, the blind Timur.

Briefly, Iris (soprano) is a poor, innocent woman, devoted to serving her father (bass). Osaka (tenor), a young nobleman in search of adventure, falls for her, and, with the connivance of Kyoto (baritone), becomes part of a traveling group of players so he can win Iris’s affections. The middle of Act 1 is a play-within-a-play, given by the performing troupe. The baritone, Kyoto, presents himself as Danjuro, the chief puppeteer; Osaka plays Jor, Son of the Sun, in order to draw the attention of Iris, who is watching the show. She is touched by the lachrymose play, just as the two men hoped. This scene echoes the final scene of Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci (1892), but gains freshness by happening near the beginning of the drama rather than as its melodramatic close. (Pagliacci is often performed nowadays on a double-bill with Mascagni’s aforementioned Cavalleria rusticana.)

Osaka and Kyoto abduct Iris, leaving her father money, plus a note that implies that Iris has abandoned him. They bring her to the geisha house that Kyoto runs. Iris awakes and, seeing the fancy accommodations, assumes she has died and gone to Paradise. Her father arrives and curses her, flinging dirt at her face. Kyoto places her by an open window to attract customers. Osaka tries to seduce her, but she resists (recalling a painted screen that showed Desire as an octopus strangling a young woman), and leaps from the house into a pit into which Kyoto had already threatened to throw her.

In the final act, Iris awakens to find rag-pickers trying to seize her fine silken clothing. She dreams she hears Osaka, Kyoto, and her father all cursing her, and she is eventually borne to Heaven by the tendrils of flowers. The image — perhaps a transmuted, now tender version of the octopus’s enlacing tentacles — could be powerfully staged nowadays. After all, the Met, for example, has all kinds of amazing machinery and visual effects available, as shown in its Ring Cycle. True, the ending might seem ludicrous to some, but perhaps no more than the endings of dozens of operas that are performed more often. The ghostly hero and leaping heroine in The Flying Dutchman?

Danish soprano Nina Clausen in Berliner Operngruppe’s 2020 performance of Pietro Mascagni’s opera Iris. Photo: Bertelsmann

Mascagni does not try to evoke Japanese music as closely as Puccini will do. One exception is a delicate passage in which (as the women’s chorus announces) “shamisens, drums and resounding cymbals and gongs” announce the arrival of the geishas and strolling musicians. Indeed, the score requires 13 tuned tamtams, to allow for perfect harmonization with the rest of the orchestra. Another possible “Asian” touch: some surprising chords in the harp accompaniment to the tenor’s famous aria “Apri la tua finestra” (“Open thy window,” sung during the puppet show). Two other well-known excerpts are the choral “Hymn to the Sun” (preceded by an orchestral sunrise) and Iris’s aria fearfully recalling the painted screen with an octopus on it.

There are many folklike features, though at times a given dance rhythm will, I suspect inadvertently, evoke some other land; for example I thought I sensed a bit of Spanish style in the chorus of the young women, “Al rio! al rio!” During that number, Iris’s voice ends up floating over the singing of the women, in a way that may have lingered in Puccini’s mind when he composed the Act 1 arrival of Cio-Cio-San and her attendant maidens.

The singers here are an international lot: a big-voiced Armenian-born soprano (familiar to filmgoers from bits of Tosca that featured prominently in the James Bond movie Quantum of Solace), a lighter soprano from Denmark, a tenor and baritone from Italy, and a Croatian bass-baritone. All have the style in their bones and sing firmly and with dramatic conviction. Unfortunately, none of them has a glamorous voice. The soprano offers one basic sonority, healthy enough but unvaried. The bass-baritone sounds dry and a bit tremulous. And the tenor and baritone seem to be pushing small voices into big roles, resulting in harshness and wobble. Still, they all catch the spirit of the work, and it “plays.”

Two directorial decisions seem odd. The Blind Man (Iris’s father) does not speak his prayers aloud during the Act 1 women’s chorus. This causes him to semi-disappear for a time. And we don’t hear Iris cry out when she is abducted, so, similarly, listeners may have no idea what has happened unless they are following the stage directions closely.

The orchestra is led with a sure hand by Felix Krieger, the Berlin Opera Group’s founding conductor, but it is small. Furthermore, the orchestral sound, as captured here, is somewhat tamped down, perhaps in order to avoid catching any noises from the audience. (The singers come through clearly.)

Armenian soprano Karine Babajanyan in Berliner Operngruppe’s 2020 performance of Pietro Mascagni’s opera Iris. Photo: Bertelsmann

Unlike Mascagni’s I Rantzau, which received its first recording quite recently (it’s his third opera; see my review here), Iris has had several notable previous recordings over the decades, featuring such major artists as Magda Olivero and Plácido Domingo. The one with Domingo (and Ilona Tokody, Juan Pons, and Bonaldo Giaotti, under Giuseppe Patanè) is still available. It’s somewhat more expensive than the new recording, but the vocalizing is a total treat to the ears. The singers also show more detailed response to the text’s changing moods. Domingo makes Kyoto sound like a real cad. And we do hear the father’s prayers and Iris’s stifled cry. The large orchestra (Munich Radio) makes glorious sounds, captured with far greater specificity (back in 1988) than what we hear, or don’t hear, in the new recording. That’s the one to get, I’d say. But try to find a used copy of the CD release; the current digital download lacks a booklet.

Speaking of which, the new recording has a fine English translation (borrowed from Bard Summerscape), but it comes after the end of the Italian original, instead of in parallel columns. This forces one to flip endlessly back and forth. Fortunately, the Bard libretto itself, in parallel columns, is, I found, available online and can be printed out.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Berlin Opera Group Chorus and Orchestra, Felix Krieger, Iris, Japanese dance, Oehms, Pietro Mascagni, japanese