Film Review: “Mad God” – God’s in His Heaven, All’s Forsaken With the World

By Nicole Veneto

Think Ray Harryhausen by way of the Quay brothers or Jan Švankmajer and you’ll have a vague sense of the sort of magnificent black magic that animates Mad God.

Mad God, directed by Phil Tippett. Release date to be determined.

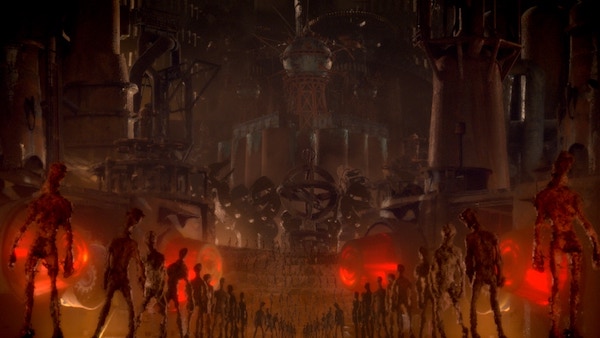

The Miltonesque hell world of Mad God. Photo: Tippett Studios

The most potent works of art come from the minds of madmen. Not “mad” in the sense that the artist literally mutilates themself or causes great bodily harm to someone else for the sake of art, but “mad” because these works emanate from the darkest reaches of the mind. Artistic vision is a kind of exorcism, from the subconscious, that takes a physical form. The debut animated feature from legendary visual effects artist Phil Tippett (Star Wars, RoboCop, Starship Troopers) is the aptly named Mad God, a film only a madman could have made — a technically audacious stop-motion nightmare 30 years in the making, born of one man’s personal neuroses and contempt for today’s CG-reliant media landscape. Think Ray Harryhausen by way of the Quay brothers or Jan Švankmajer and you’ll have a vague sense of the sort of black magic that’s animating Mad God.

Production on Mad God began while Tippett was working on RoboCop 2 in 1990, shooting bits and pieces over the next several years. With the success of 1993’s Jurassic Park, Tippett subsequently shelved the project because he (correctly) discerned that the future of filmmaking would be beholden to computer generated effects. Stop-motion animation was a dying art, and to Tippett, the dinosaurs he’d helped bring to life were the final nail in the coffin for practically done effects. Some 20 years passed, and the animator was eventually convinced to revive Mad God at the behest of both friends and fans of his work, some of whom volunteered to help the director complete the project with the aid of a Kickstarter campaign to raise production funds. Mad God is thus both a painstakingly laborious work of artistic creativity as well as a deeply personal product of one man’s consciousness. At one point during production, Tippett suffered a psychotic breakdown because he’d completely thrown himself into completing the film at the cost of his own mental health, resulting in a week-long stay in a psychiatric ward where doctors diagnosed him with bipolar disorder.

A denizen of the surreal world of Mad God. Photo: Tippett Studios

It’s difficult to summarize what happens in Mad God because so much of it reflects Phil Tippett’s roiling psyche. If there’s a narrative structure or logic to what happens, only Tippett knows, like shards of half-remembered dreams strung together into little vignettes of free-association and psychological masochism. Per the movie’s official website, the film is set in “a darkly surreal world” of “monsters, mad scientists, and war pigs” wherein “the creatures and nightmares of [Tippett’s] imagination [can] roam free.” More importantly, Tippett’s nightmare realm is lorded over by an angry, wrathful god who’s laid cities in desolate ruin for future generations of humanity — the work of a mad god, if you will. The very first shot is of the Tower of Babel as it’s engulfed by a lightning storm, a fitting act of divine punishment for humanity’s hubris, according to the subsequent passage from Leviticus 26:27: “If you disobey me and remain hostile to me, I will act against you in wrathful hostility.”

A figure credited only as The Assassin descends from the skies in a diving bell like a soldier parachuting into a war zone, the air exploding around him as he’s lowered through multiple levels of postapocalyptic hell. Guided only by a tattered map that’s falling to pieces, The Assassin makes his way past various monstrosities and grotesque abominations that recall the dystopian surrealism of Zdzisław Beksiński and H.R. Giger. Flesh and steel have merged into gruesome machines that feed excrement to giant mutant creatures. Large unmanned turrets and blinding spotlights monitor slaves manufactured out of fuzzy twine to carry out menial labor and then be crushed, ground up, or horrifically beaten to death by their deformed masters. Heaps of suitcases and mangled bodies pile up like mountainous remnants of a holocaust. The world of Mad God is a visceral inferno filled with dark and nasty things, a labyrinth of bombed out wastelands where the law is governed by a brutally oppressive atmosphere brimming with human suffering. There is no god here, and if there is, he’s very, very angry with us.

I’ve gone on the record multiple times that I prefer the tangible weight of practically done effects to the sleek perfectionism of CG. It is not because I think CG is inherently bad, but because practical techniques like stop-motion make the craftsmanship of filmmaking more readily visible. CG is an incredibly useful tool for creating visual spectacle, yet it’s over-relied upon for convenience’s sake, replacing on-set ingenuity and camera trickery with the uniformity of postproduction software. It algorithmically smooths over the imperfections and traces of labor otherwise evident in practical effects in order to simulate some sense of “realism” on screen, often achieving the very opposite effect. Computers don’t make movies, people do. Even when practical effects look less than convincing, you’re more likely to think about the collective effort that went into crafting them than you are about anyone in the gargantuan wall of names credited as a VFX artist for a Marvel movie. Tippett is an old-school artist who’s largely resisted the compulsion toward CG visual effects. Mad God offers a firm rebuttal against its supremacy in today’s media landscape. I can’t imagine anything in this film being as viscerally impactful if it were rendered in 3D as opposed to stop-motion animation. It’s supposed to be upsetting to look at — that’s the point.

Mad God — in the operating room with a mad surgeon. Photo: Tippett Studios

There’s one place where Mad God falters though, and that’s in its use of live-action actors. Halfway into the movie, The Assassin is captured and dissected by a mad surgeon and his assisting nurse, both played by costumed actors in front of a less than convincing green screen. Then, Repo Man director Alex Cox shows up in a bathrobe with ludicrously long press-on acrylics. (I had to double-check that my screener wasn’t corrupted.) If the purpose of using live-action performers is to be disorienting, then Mad God achieves that, albeit in a way that’s noticeably disjointed from the rest of the film. If you’re familiar with the infamous Dick Jones puppet at the very end of RoboCop (a perfect movie), this sudden jankiness might not be as surprising to you. It’s simply an aesthetic choice that doesn’t mesh with everything else. Nevertheless, it’s a relatively minor distraction considering how incredible the majority of Mad God is.

Though Tippett is responsible for some of the most iconic visual effects in Hollywood cinema, the industry has drastically changed since the ’90s, and so has Tippett’s role within it. Before Mad God, his last major VFX credit was designing the werewolves in the Twilight movies, which I can only imagine was a paycheck gig he took on before his total disillusionment with Hollywood. Despite a successful festival run throughout 2021, as of January 2022, Mad God still doesn’t have a distributor. Sadly, a feverish stop-motion film about how god has forsaken us and the world is a never-ending cycle of blood, guts, and shit doesn’t command audiences’ attention like glossy intellectual properties played by actors in mocap suits fighting CG monsters now do. Whenever Mad God is unleashed upon the unsuspecting public, it’ll probably be greeted with head-shaking confusion and revulsion by some. A shame, because Tippett’s magnum opus is a testament to both artistic dedication and the psychological darkness that resides within all of us.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the new podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and Twitter @kuntsuragi for weird and niche movie recommendations.