Country Album Review: Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Classic Trio Albums” — The Voice Alone

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

What makes these two albums stand apart? They are content to showcase the elemental power of Tennessee Ernie Ford’s voice.

Tennessee Ernie Ford in the late ’50s.

Ernest Jennings Ford, or “Tennessee” Ernie Ford, was just eight years old in 1927 when hordes of musicians descended on the small, twin Appalachian towns of Bristol, VA, and Bristol, TN. The group, which included the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, had traveled from all over the South to Ford’s hometown for an opportunity, over 10 days, to sing into the Victor Company’s “recording machine”. The young Ford couldn’t help but see opportunity: the new-fangled record business had already been credited with making a success of singer, songwriter, and guitarist Ernest V. Stoneman, who reported in local media that he was earning three-and-a-half times the area’s average annual salary. Bristol was located where two states and two railroad lines met. The town offered a young man two choices: a life filling hopper cars with coal or, if gifted with a talent to entertain, a chance to feed American nostalgia for country life. Given his down-home bass-baritone, Ford chose the latter, and surely thought he’d struck quite the bargain with fate.

By 18, Ford became a local radio announcer. From there he would move onto announcing jobs in Atlanta and other large cities in the region. He spend a short time at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music with the objective of becoming an opera singer. After serving in the Pacific in the Army Air Corps, he relocated to his wife’s home state of California. There, in Pasadena, he developed the winning radio personality of “Tennessee Ernie Ford” — the exaggerated, “hillbilly” persona who chimed in after the respectable “E. Jennings Ford” read the news. This duality would follow him throughout his career: he would fit conventional notions of “respectability” and “Middle America” and then serve up caricatures of Appalachian, rural, or Southern stereotypes. Country singer Cliffie Stone initially went to Ford’s studio in search of a man named “Tennessee,” unaware that he and E. Jennings were one and the same.

Joining Stone’s Hometown Jamboree program made Ford a local TV personality, and that notoriety soon kicked off his musical career. “The Shotgun Boogie,” recorded with the Hometown Jamboree band, launched Ford on the Country & Western charts. Other television opportunities quickly materialized, mostly for “Tennessee” rather than “E. Jennings,” but it was clear that Ford’s success was driven by his skill at blending his two identities: operatic voice and country vernacular, roots and respectability, modernity and tradition. The reassuring fusion hit a postwar sweet spot. His 1955 cover of Merle Travis’s song “Sixteen Tons” — a coal miner’s lament over perpetual debt, danger, and poverty — became, unexpectedly, a humongous pop success, reaching #1 on the Billboard charts. In 1958 he would begin hosting his own NBC show.

Joining Stone’s Hometown Jamboree program made Ford a local TV personality, and that notoriety soon kicked off his musical career. “The Shotgun Boogie,” recorded with the Hometown Jamboree band, launched Ford on the Country & Western charts. Other television opportunities quickly materialized, mostly for “Tennessee” rather than “E. Jennings,” but it was clear that Ford’s success was driven by his skill at blending his two identities: operatic voice and country vernacular, roots and respectability, modernity and tradition. The reassuring fusion hit a postwar sweet spot. His 1955 cover of Merle Travis’s song “Sixteen Tons” — a coal miner’s lament over perpetual debt, danger, and poverty — became, unexpectedly, a humongous pop success, reaching #1 on the Billboard charts. In 1958 he would begin hosting his own NBC show.

Success did not come without a cost. Ford struggled with alcoholism and depression, perhaps because he was trying to balance his personal life and his celebrity. He felt unable to protect his home from a commercial world that he was bringing into rural living rooms. For the rest of his career, Ford struggled to repeat the explosive success of “Sixteen Tons.” Crossover attempts and sickly sweet overproduction didn’t do the trick. Ford would find moderate but steady sales with his gospel records, which brought him some genuine satisfaction. Two non-gospel albums, however, stand apart as examples of where Ford comfortably forgot both “Tennessee” and “E. Jennings.”

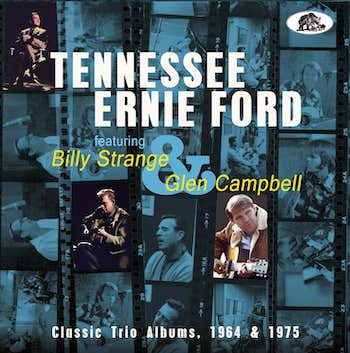

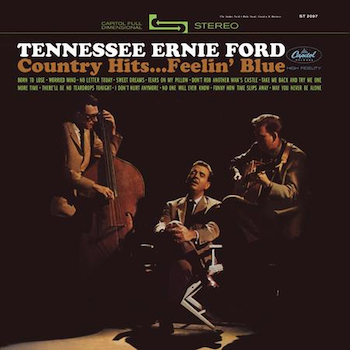

Those two albums are now available on CD (as Classic Trio Albums, 1964 & 1975) by the Bear Family, a release enriched by the excellent editorial and curatorial assistance of Appalachian music expert Dr. Ted Olson. The two original albums were 1964’s Country Hits… Feelin’ Blue with Billy Strange (never previously released on CD) and 1975’s Ernie Sings and Glen Picks with Glen Campbell. What makes these two albums stand apart? They are content to showcase the elemental power of Ford’s voice. It is almost as if he were back in Bristol, invited to sing into Victor’s machine. According to Olson, Ford “regularly sang at home and at church not as a celebrity for a mass audience but as a member of a beloved community — for the pleasure of others and for his own pleasure.”

Country Hits… Feelin’ Blue was the direct result of Ford’s NBC show. Its tracks are one-and-done studio recordings in the spirit of the unadorned and unaccompanied performances that Ford presented on his variety show. Arriving a decade later, Ernie Sings and Glen Picks was an attempt to reproduce the magic of the 1964 recording with some help from a rising star of the new “countrypolitan” sound. Neither Campbell nor Ford were singing what they were popular for, but it is clear that they both were profoundly in their elements. In both of these albums there is an earnestness, a loyalty to the rural sensibility, that rebukes the marketing of the country music industry.

As Olson accurately notes, “To some listeners, Ford’s approach to country music on the two albums might seem more evocative of the parlor than the honky tonk, yet such people should bear in mind that country music as an art-form inhabited parlors long before it provided solace at honky tonks.” In fact, Ford’s career straddles the parlor music of his childhood and the honky tonk sound demanded by the suits. And that is key to why he couldn’t recreate his crossover success with “Sixteen Tons.” At his core, Ford was a parlor singer, not a honky tonk belter. (He was just as much the latter as he was the opera singer “E. Jennings” or the bumpkin “Tennessee.”) In the American entertainment industry these kinds of tensions and contradiction are not unusual. For example, Buell Kazee was a classically trained vernacular musician. But, in Ford’s case, the pressure to sell country music came at a time that popular culture was undergoing a considerable shift.

As Olson accurately notes, “To some listeners, Ford’s approach to country music on the two albums might seem more evocative of the parlor than the honky tonk, yet such people should bear in mind that country music as an art-form inhabited parlors long before it provided solace at honky tonks.” In fact, Ford’s career straddles the parlor music of his childhood and the honky tonk sound demanded by the suits. And that is key to why he couldn’t recreate his crossover success with “Sixteen Tons.” At his core, Ford was a parlor singer, not a honky tonk belter. (He was just as much the latter as he was the opera singer “E. Jennings” or the bumpkin “Tennessee.”) In the American entertainment industry these kinds of tensions and contradiction are not unusual. For example, Buell Kazee was a classically trained vernacular musician. But, in Ford’s case, the pressure to sell country music came at a time that popular culture was undergoing a considerable shift.

Olson describes the approach of these two records as “a bold production decision at the time.” Their simplicity departed from an increasing dependence on overproduction. What’s more, four fab young blues fans from Britain would displace Ford’s top position at Capitol Records. Ford’s commercially fine-tuned, polite and humble Americana, though nominally apolitical, was beginning to sound hollow in the mid-’60s. Still, it is illuminating to look at things a bit differently. In 1960, Ford cheerfully pleaded in song on national television for Americans to stop thinking of violence and to “think about living” instead. This is proof that something of the sincere gospel singer remained, underneath the Naugahyde and Teflon. This was a boy from a coal town asking us to choose peace.

We catch glimpses of that coal town kid in these recordings. According to Olson, Ford “is most himself” in these albums, and “his singing transcends time and place; he is singing just for you, where you are, now.” Headliners bucked trends at their peril: it was “risky in that era for a prominent mainstream entertainer — a television star no less — to record something so plain, so lacking in embellishments.” He was outgunned, but Ford was opposing the patronizing country gaucherie promulgated by TV ratings kings The Beverly Hillbillies and Hee Haw. Classic Trio Albums, 1964 & 1975 gives us a chance to appreciate the artistry — and authenticity — of the losing side.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: Billy Strange, Country Music, Glen Campbell, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Tennessee Ernie Ford

Interesting, I enjoyed reading this article. What a voice. I like watching his show on U tube.