Arts Remembrance: Michael Nesmith

By Jason M. Rubin

With Michael Nesmith’s passing, Boomers of a certain age feel another piece of their youth disappearing.

The Monkees in 1967 — Michael Nesmith is at the center. Photo: Wiki Common

Michael Nesmith tried, but could never shed his comic image as the green-wool-hat-wearing member of The Monkees, the Emmy Award-winning television sitcom inspired by A Hard Day’s Night that ran for two seasons and spawned sales of millions of albums, singles, and collectibles. Though he’d been a recorded singer-songwriter prior to becoming a Monkee, and had a prolific and criminally underappreciated solo career for decades afterwards, you could never read a profile of him without seeing him referred to as “the smart Monkee” or “the quiet Monkee” or the “serious Monkee.” The Monkee years — which continued after the series was canceled, resulting in more albums and TV appearances — brought him fame, money, and an albatross he wrestled with for many years, before he decided in the late ’80s to join his colleagues in select reunion projects. Over the last two decades, he seemed to fully embrace his Monkeehood by touring solo and with whichever other Monkees were still alive, right up to a few weeks ago when he played the Chevalier Theatre in Medford with Micky Dolenz. With Nesmith’s death on December 10 of heart failure, Dolenz is the sole remaining Monkee.

At the outset, this writer wants it on the record that he believes the Monkees should be in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. They have the sales, the success, the quality, and the longevity to be inducted. What keeps them out is the false accusation that the Monkees were never a real band, just a prime-time fabrication featuring four actors who didn’t write their own songs or play their own instruments. First of all, this wasn’t true — Nesmith had a pair of compositions on each of the first two Monkees albums, and that only grew over time (one song he’d written that the show’s producers turned down was “Different Drum,” a hit for Linda Ronstadt’s band the Stone Poneys). Second, recent documentaries about the Wrecking Crew, Motown’s Funk Brothers, and the Muscle Shoals’ Swampers have made it clear that many big artists of the ’60s and early ’70s didn’t play their own instruments. But the Monkees did. Not on every album, but they did. Every one of them. And they wrote, too. But mainly they were great singers, so if the Temptations could get into the Hall of Fame without picking up a guitar, so should they.

But the Monkees, it seemed, were never meant to be taken seriously. They were goofy, and the charm of the show is that they were an unsuccessful band, struggling to get a break. But one person took the music seriously, and that was Nesmith. From the get-go, he fought for creative control and autonomy for the group. He protested against Don Kirshner picking the songs and recording the tracks without their involvement. Eventually, thanks to the leverage they enjoyed as big stars (ironically, thanks to Kirshner), Nesmith won the freedom the band sought. The result was the album Headquarters, which hit number one for one week, then stayed at number two for 11 weeks, kept under only by the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Their next album, Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd., was even better and became the Monkees’ fourth consecutive number one album.

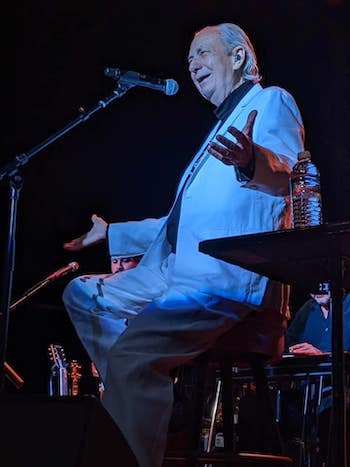

Michel Nesmith in 2021. Photo: Wiki Common

Even so, any mention of the Monkees today typically includes the word “zany” or “slapstick,” which must have been an annoyance to Nesmith. He released an album of quirky big band arrangements of a number of his Monkees compositions in 1968 under the moniker The Wichita Train Whistle, and eventually left the group the following year. In 1970, he emerged with the First National Band. While his songs for the Monkees had helped launch country-rock four years earlier, the First National Band’s trilogy (Magnetic South and Loose Salute in 1970, and Nevada Fighter in 1971) codified the new fusion and became cult classics — while the much less quirky Eagles sold millions of records with a similar formula.

Nesmith issued three more interesting albums before releasing what this writer feels is his masterpiece: The Prison. Subtitled A Book with a Soundtrack, the 1974 release included a 48-page book about the artificiality of self-imposed limitations, along with an album of songs that were conceptually related to the text but with different words. The idea was to read the volume and listen to the recording together — the aim was to achieve a synergy through multiple creative stimuli. Though an uncommercial concept, the experiment yields significant rewards and, of course, the book and the record can each be enjoyed separately.

In the ’80s, Nesmith ventured into film and home video, winning the first ever Video Grammy for 1981’s Elephant Parts. More importantly, he is credited with inventing the music video programming concept that became MTV (much like his own mother invented Liquid Paper). A philosophical intellectual, Nesmith served as trustee and president of the Gihon Foundation in the ’90s, which convened thinkers from different fields to identify the most critical issues facing humanity and the planet. In recent years, he authored two novels and an autobiography. In 2018, he underwent quadruple bypass heart surgery; on his final tour, he appeared fragile and unsteady.

With Nesmith’s passing, Boomers of a certain age feel another piece of their youth disappearing. Perhaps now they will take the time to listen to Michael Nesmith and the Monkees with the respect and appreciation they deserve. The music stands up and will continue to do so. Yes, the Monkees were a real band and a damn good one. But Nesmith was more than a Monkee. He was a thoughtful, curious visionary who had success in multiple media — television, music, film, literature, video — and truly marched to the beat of a different drum. He will be sorely missed.

Jason M. Rubin has been a professional writer for more than 35 years, the last 20 as senior creative associate at Libretto Inc., a Boston-based strategic communications agency where he has won awards for his copywriting. He has written for Arts Fuse since 2012. Jason’s first novel, The Grave & The Gay, based on a 17th-century English folk ballad, was published in September 2012. His current book, Ancient Tales Newly Told, released in March 2019, includes an updated version of his first novel along with a new work of historical fiction, King of Kings, about King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Jason is a member of the New England Indie Authors Collective and holds a BA in Journalism from the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Thanks for this great tribute. The joke is on the Rock Hall of Fame, since the music video that Nez pioneered has far outlasted the notion that pop music has to come from four friends in a garage who write all of their own songs.