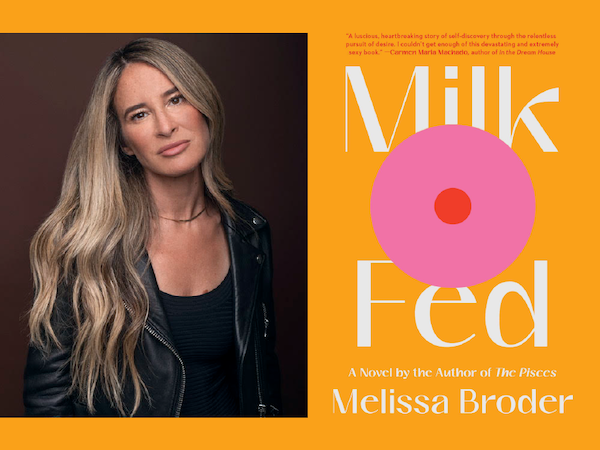

Book Review: “Milk Fed” — The Glory of the Zaftig

By Clea Simon

For all the sensual lushness of Melissa Broder’s writing, that hard center remains, one where appetite invites awareness, bringing with it pain as well as satiety.

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder. Scribners, $26, 304 pp.

The spirit is never far from the flesh for Melissa Broder, but it’s never superior to it, either. For the Los Angeles–based poet and novelist, the two mix and merge in a constant tug of war, and the results are unexpected, explicit, and, well, weighty.

In Broder’s first novel, The Pisces, the conflict took the form of merman erotica, as a lonely Los Angelena found mind-blowing sex with a mythical half-man half-fish. Weird, and weirdly arousing, the story dove deeper, of course, when the impracticality of the relationship tapped into its protagonist’s desire for annihilation, an Eros-Thanatos face off for the ages.

In her latest, Milk Fed, the body and the spirit are once again at odds in a battle that becomes externalized into another impossible affair. As the book opens, Rachel, our protagonist and the book’s narrator, is at war with herself. A lapsed Jew whose only family tradition is counting calories, at 24 she has internalized the critical and unloving mother who equated fat with failure and slimness with success. Her mind is holding the line, but only barely. Reflecting on her sparsely furnished, monochrome apartment, she has the self-awareness to note, “I felt that committing to a rug would mean I existed on the planet more than I actually wanted to exist.”

Rachel’s whippet-thin body is the ultimate manifestation of her will, and the extremely demanding and rigid routine of eating and exercising allows her to block out all else, including her dissatisfaction with her job at a bro-ish talent agency — until it doesn’t. Although Rachel hopes for “a subconscious, hypnotherapeutic modality,” her therapist pushes for the much more annoying “real action.” Urged to give form to her fears with the cleverly named Theraputticals modeling putty, Rachel creates the figure of a woman with “massive thighs, weighty calves, a voluminous ass.” With the casual frankness that distinguishes Broder’s prose, Rachel acknowledges, “It was a shape that had always lived inside of me. It was destined to come out. What was even scarier was how much my hands liked this.”

That zaftig form appears to come to life when a new employee appears at the frozen yogurt stand where Rachel indulges in her one strictly regulated splurge. The new server, Miriam, not only ignores Rachel’s precise requests about serving size, she prods the regular to try calorie-rich toppings too good to be discarded. It doesn’t help that Miriam is fat — “undeniably fat, irrefutably fat”; she’s also apparently unashamed of her weight, and as juicy as a ripe peach. Seeing her, Rachel’s thoughts run immediately to food: “On one of her round cheeks was a small brown beauty mark, like a caramel chip from the toppings bar…. On her neck was a triangle of three darker moles: a dark chocolate drop on her Adam’s apple, framed by two milk chocolate drops to the left.”

Deprived for so long, Rachel succumbs, and Broder neatly depicts her pleasure and shame as she takes her overfilled indulgence out back by the trash where “I could eat in self-disgust and peace.” More than one appetite has been awakened, however, and Rachel accepts an invitation to dinner, unsure of what the big woman really wants — or even how humans interact. “Maybe this was how normal women made friends with other women,” she tells herself. “They invited them to do shit like eat in public.”

When it becomes apparent that Miriam is attracted to Rachel as well, it would seem that her cup runneth over.

But Miriam is not simply abundance personified, a Golem-like figure who will fight off Rachel’s demons. She’s also an Orthodox Jew, and as she invites Rachel into her life, she piques other hungers in the nonpracticing Reform Jew. For Rachel, faith appears at first to be another comfort to indulge in, compatible with luxuriating in food and flesh. However, her very existence raises worrying issues for the previously happy-go-lucky Miriam. A true believer, Miriam wants a heterosexual marriage and many children; to her, as well as to the family to which she is devoted, a lesbian relationship is sinful, and Rachel’s increasing liberation only complicates matters further. If Rachel isn’t exactly the merman in this story, she’s something close — an embodiment of a desire so strong that it can acknowledge impossibility and yet still push for it.

“I was a woman of impulse, a woman of instinct,” she discovers, during a scene of explicit and mesmerizing erotica. Broder knows how to write sex. More to the point, she knows what it can mean. “I was a woman of pleasure and a woman of confidence. I was a woman of appetites, a growling beast. I was a person.”

For all the sensual lushness of Broder’s writing, that hard center remains, one where appetite invites awareness, bringing with it pain as well as satiety. In its way, Milk Fed can be read as Broder’s exploration of the vision of the poet William Blake, who in his “Proverbs of Hell” wrote, “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” That road, she shows us, can be bumpy, but at least the palace probably has a rug.

Somerville-based novelist Clea Simon is the author most recently of the psychological suspense Hold Me Down. She can be reached at www.CleaSimon.com.