Book Review: “Museum of Fine Arts Boston: 1870 to 2020, An Oral History” — Questioning the Elite

By Mark Favermann

This is an invaluable gathering of interviews, an impressive excavation of institutional memory that not only recognizes the MFA’s grandeur but its many deficiencies as well.

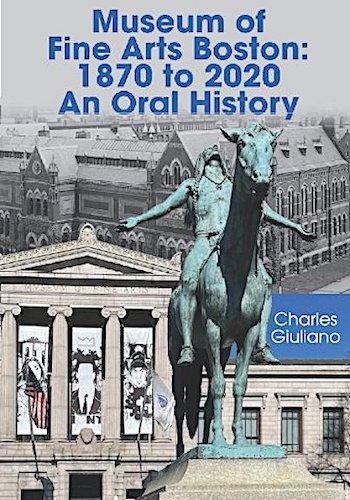

Museum of Fine Arts Boston: 1870 to 2020, An Oral History by Charles Giuliano. Berkshire Fine Arts, LLC, 320 pages, $25.

The Museum of Fine Arts Boston (MFA), the Grand Gray Lady on Huntington Avenue, has asserted itself as a major cultural icon and institution for over 150 years. Born in 1870 in Boston’s Back Bay, the institution has been a reassuring mecca for Boston Brahmins, both in terms of membership and leadership. After its 1912 move to its current address in the Fenway, the museum began its climb to its current apex: it became one of the major comprehensive arts institutions in the world, a position it still maintains. Over the years, alongside its dedication to consistency, aesthetic and historical, the MFA has often reflected its times — politically, culturally, and socially.

The Museum of Fine Arts Boston (MFA), the Grand Gray Lady on Huntington Avenue, has asserted itself as a major cultural icon and institution for over 150 years. Born in 1870 in Boston’s Back Bay, the institution has been a reassuring mecca for Boston Brahmins, both in terms of membership and leadership. After its 1912 move to its current address in the Fenway, the museum began its climb to its current apex: it became one of the major comprehensive arts institutions in the world, a position it still maintains. Over the years, alongside its dedication to consistency, aesthetic and historical, the MFA has often reflected its times — politically, culturally, and socially.

Critic, publisher, and arts journalist Charles Giuliano has interviewed key MFA leadership players for over the past 50 years. These often insightful and always thoughtful interrogations have been organized into a comprehensive compendium, a mostly chronological look at the venerable — at times, even vulnerable — museum’s talking points. In Museum of Fine Arts 1870 to 2020, An Oral History Giuliano has created a kind of drama out of his give and take with quite a few of the institution’s rather distinct characters — the good, bad, and even the somewhat ugly.

Giuliano’s relationship with the MFA dates back to his first visit as a small boy in 1949. After graduating Brandeis University in the early 1960s, he became a conservation intern in the museum’s Department of Egyptian Art. He worked there for the next two and a half years. In 1968, he began interviewing every MFA director that came along, from the imperious Perry Rathbone to the cerebral current director Matthew Teitelbaum. Along the way he expanded his focus, talking with prominent trustees, administrators, curators, art historians, and critics.

This Herculean effort has been turned into a readable and accessible narrative that humanizes both high culture and institutional politics. This 50-year background narrative also informatively frames the social and cultural history of Boston and New England. Though often a bit too polite, Giuliano does probe uncomfortable perspectives: his interviewees suggest in their own words (and sometimes between the lines) a legacy of elitism, anti-Semitism, misogyny, and racism. The interviewer stands back and lets the volume’s cast of characters expose their prejudices. Here are the ghosts of Boston’s pitilessly layered society, the blinkered goblins of conservative culture, the trollery of the snobbish. Today, these issues, because of the Me Too and Black Lives Matter movements, are challenging business-as-usual at the MFA and other cultural institutions. One of the saving graces of the current director is his determination to move the museum to aggressively address these problems.

Unusually, this is the story of an institution told through the voices of those who worked loyally within it. These are clearly rendered portraits of various important players — some carefully theatrical, wearing makeup, and some displaying warts and all. Another wonderful aspect of the book is that it draws on Giuliano’s scholarly knowledge of art history: the spotlight is less on artists than on the decisions made by administrators, trustees, and curators about great works of art.

The MFA director interviews include talks with the patrician, rather imposing Perry T. Rathbone, an obviously in-over-his-head Merrill C. Rueppel, and an uncomfortable Alan Shestack. Of course, there is a chat with the longest-serving and most dictatorial of the lot, Malcolm Rogers. Current director Teitlebaum is also heard from. He was left to pay off the debt accrued by Rogers’s misguided decision to push ahead with a muddled architectural expansion. A physical metaphor at the museum for Rogers’s tenure is the awful Las Vegas-like glass sculptural tower by Dale Chihuly — flashy, imposing, but not very good.

Curators interviewed included the MFA’s first contemporary specialist, Kenworth Moffett, Uber-curator Theodore Stebbins, Amy Lighthill, pure of heart but limited in scope, and the long-term African American art specialist Barry Gaither. In the course of the chats, they each reveal their own personal quirks, limitations, and agendas.

Regarding the trustees interviewed, they range from the museum-as-business sensibility of George Seybolt to the insipid Brahmin wheeler-dealer Lewis Cabot and the generous art lover Graham Gund. The money-spotlit strategy of Seybolt and the purge and consolidation actions of Rogers proved to be a difficult fit for the nonprofit MFA. Each predictably ran into problems.

Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Photo: Elan Fleisher/REX/Shutterstock

Giuliano follows up on several concerns in these interviews, particularly pointing out the MFA’s sadly limited modern and contemporary art collection. (With the exception of donations and occasional modest acquisitions, the MFA’s leadership gave up on modern art that came after the French Impressionists.) In this area, the MFA does not compare to other more minor and major museums in New England, the US, and the world. Another bone of contention: until very recently, the Boston Expressionists, a mostly Jewish group of locally trained artists, have been ignored by the MFA. Because of anti-Semitism? And, last but not least, contemporary local artists continue to be undershown and uncollected by the MFA, particularly the work of women as well as Black and Brown artists.

Museum of Fine Arts Boston: 1870 to 2020, An Oral History has its flaws. The volume contains a lot of repetition (which might have been edited out) and is missing a clear timeline of directors and curators. Casual readers may be overwhelmed by all the in-the-weeds details. Also, it is good to have Giuliano’s foreword — but where is his afterword, his summary? Perhaps that can be added in the book’s second printing? Still, even with these limitations, this is an invaluable document, an impressive excavation of institutional memory that recognizes not only the MFA’s grandeur but its many deficiencies as well. It is also an inspiring testament to Giuliano’s steadfastness. Here is the rare art critic/historian who has never abandoned his beat.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

There are two encyclopedic museums in America, the MFA and Met. Both were founded in 1870. The met is bigger with deeper pockets. In specific collections, however, the MFA is second to none: Asiatic, Old Kingdom Egyptian and Nubian, Classical Greek and Roman, prints, drawings and photography, American art through 1900. For European painting and French impressionism the MFA compares to the Met, National Gallery, Art Institute of Chicago and Philadelphia Museum. For modern and contemporary art the MFA collection is weak and spotty. The development of the world class collections is discussed in the book but not in the insightful Favermann review.

It took me months to read which is why my review just came out on my blog and even then I didn’t get the whole story. But there are little gems hidden in the interviews that reveal the politics that have been rife throughout the history of the MFA. As Faverman suggests a timeline would be of great help. https://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2022/04/charles-giulianos-150-years-celebration.html

I would add that the MFA also has impressive collections of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean art. I have brought many international student tours to the MFA and a pleasant surprises for my Chinese, Japanese and Korean students has been the substantial holdings from Asia. There is also an extraordinary collection of Persian miniatures. Full disclosure (1), the commercialized post-Warhol art world holds little interest for me, so the relative dearth of contemporary art doesn’t trouble me. But I don’t think that the book is a intended as

a cultural critique of curatorship. Anyone who knows Charles Giuliano is well aware that “forthright” is his byword. This book is a major contribution to social and art history. (2) Charles Giuliano and I once taught at the same university but in different departments.

The MFA moved from its location in Copley Square to Huntington Avenue in 1909. I am an MFA Senior Associate.

Bring back Malcolm Rogers! Often infuriating, but at least he was never dull. In comparison Teitelbaum is SO boring I have trouble remembering his name . . .

Glad to know about this book. I will tell several cultural historians and others who will be interested. As some readers may know, Isabella Stewart Gardner was building her own, much smaller museum at the same time that the MFA was amassing its collections, so the two institutions-in-progress sometimes were competing for the same items.

I have published a book chapter about the music-making that went on in the Gardners’ several homes, including the future Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (“Fenway Court,” as she called it). It’s in a University of California Press book that is now online, open-access: http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft838nb58v;brand=eschol

(pp. 90-121; also a supporting document: “Playing for Mrs. Gardner Alone: The Violinist Harrison Keller Reminisces”–letter annotated by me, pp. 122-23).

Those of us who are degreed art historians with domestic and international museum training thank you for this enlightening exposure. We will be eternally appreciative. Arigato.