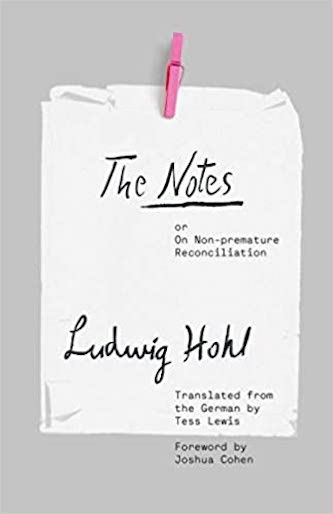

Book Review: “The Notes” of Ludwig Hohl — “Everything Ever Created Was a Fragment.”

By Alexandra Sattler

Ludwig Hohl belongs in the line of such lucidly contentious thinkers as Karl Kraus, Pascal, and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, commentators whose writing oscillates between the traditions of literature and philosophy.

The Notes or On Non-Premature Reconciliation by Ludwig Hohl. Translated from German by Tess Lewis. Yale University Press, 392 pp., $37.50.

The Notes is the magnum opus of the Swiss writer Ludwig Hohl (1904-1980), and it should be celebrated: it is wonderful that this volume of his compact, aphoristic observations has finally arrived in English. Tess Lewis’s triumphant translation must also be cheered, given the demands made by the complex compression of Hohl’s prose. He is unknown here, but Hohl has amassed a diverse group of international admirers, including Max Frisch, Peter Handke, Elias Canetti, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Bertolt Brecht, George Steiner, and the philosopher Hans Saner. As Lewis notes in her acute introduction, “Hohl has remained a writer’s writer, if not a writer’s writer’s writer.” A sincere compliment that, for some wary readers, indicates an author of forbidding difficulty. In fact, Hohl belongs in the line of such lucidly contentious thinkers as Karl Kraus, Pascal, and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, commentators whose writing oscillates between the traditions of literature and philosophy. Among his literary influences: Gide, Proust, Goethe, Katherine Mansfield, Balzac, and Valéry.

The Notes is the magnum opus of the Swiss writer Ludwig Hohl (1904-1980), and it should be celebrated: it is wonderful that this volume of his compact, aphoristic observations has finally arrived in English. Tess Lewis’s triumphant translation must also be cheered, given the demands made by the complex compression of Hohl’s prose. He is unknown here, but Hohl has amassed a diverse group of international admirers, including Max Frisch, Peter Handke, Elias Canetti, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Bertolt Brecht, George Steiner, and the philosopher Hans Saner. As Lewis notes in her acute introduction, “Hohl has remained a writer’s writer, if not a writer’s writer’s writer.” A sincere compliment that, for some wary readers, indicates an author of forbidding difficulty. In fact, Hohl belongs in the line of such lucidly contentious thinkers as Karl Kraus, Pascal, and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, commentators whose writing oscillates between the traditions of literature and philosophy. Among his literary influences: Gide, Proust, Goethe, Katherine Mansfield, Balzac, and Valéry.

Unlike a number of those other writers on those lists, Hohl strove to rise about current events in his prose. His discipline is impressive. He wrote The Notes while he was living from 1934 to 1936 in the Netherlands in a self-imposed exile. He never mentions National Socialism. Although Hohl does not address politics directly, he condemned fascism and, because of his own poverty, had an astute awareness of social inequality.

The Notes is a book about the purpose of life in the face of death. Given finality’s inevitability, what is to be done? “Human life is short.”

It’s a fatal mistake to believe — or, more exactly, to preserve the childish belief — that life is long…. For our actions to be worthwhile, we must undertake them fully conscious of life’s brevity.

From this acute sense of mortality arises Hohl’s belief that doing something, work, is the only thing that makes life meaningful. By work he does not mean the daily 9-to-5 grind, but an exploration and application of one’s own creative abilities to their fullest. This could mean artistic creation or any other nonalienating, life-affirming activity whose purpose is to strengthen the self. If there are challenges — practical or financial — then the most important task is to diminish these obstacles. With that goal in mind, The Notes can be read as a kind of instruction manual on how best to develop one’s creative powers. Hohl extols the powers the mind needs to carry on this quest, such as imagination, choice, belief in oneself, courage, and patience. (In his allegiance to self-improvement he was hugely influenced by Gide.)

The Notes are a part of what is called Hohl’s note-work (Notizenwerk), writing that comprises the middle part of a previous book entitled From Nuances and Details and a later work, From the Invading Margins: The After-Notes. (Neither have yet been translated.) Apart from The Notes, Hohl published a few short prose pieces, a diary, and a memoir. On the whole, his writing took the form of the note, which ranges in length from a short sentence to over a few pages. He eschews irony and pretentiousness — Hohl inevitably draws from lived experience. The strength of his prose is generated from the epiphanies crystallized in his deftly shaped, compact statements. The Notes are meticulously ordered; there is a well-known photo of him arranging them on a clothes-line, until he was satisfied. This obsession with order is manifest in the detailed index Hohl compiled; it was a way for him to continually rework and re-explicate throughout his life his thoughts about work. Lewis describes this interlocked intellectual structure beautifully: “Reading the resulting work is like entering the skeletal structure of a literary-philosophical geodesic dome: the notes are intricately interwoven in patterns that repeat with variations and form an elegant whole punctuated with light and openness. They are, in a sense, the inventory of one man’s soul.”

Hohl insisted on the book’s unity, its systematic nature, though this unity is not immediately obvious. One can perhaps best see this harmony as the reflection of the author’s overarching idea: driven by his consciousness of life’s brevity, man cultivates his creative powers to the point that he arrives at a stage of serenity, or what Hohl deemed “non-premature reconciliation.”

It will help to read The Notes with a grasp of the meaning of Non-premature Reconciliation, one of Hohl’s favorite ideas. The book’s subtitle can’t be fully understood by consulting The Notes alone. Only in the After-Notes does the author provide his most accessible definition of the term. There he writes, “When a person arrives at reconciliation non-prematurely: that means with open eyes, in full knowledge of our conditions and the cruel facts of reality — for example the huge law of waste — then a person sees the Real.” Two aspects of this statement are important. First, that Non-premature Reconciliation is a reconciliation with life and the world, a state of serenity that is non-premature because it can only be reached after reconciliation has acknowledged life’s cruelty. Thus Hohl’s notion of work is essentially life-affirming. You might argue that Non-premature Reconciliation is Hohl’s expression of amor fati. Second, there’s the meaning of the Real. Hohl distinguishes between two different realities. In German, they are expressed by the words Wirkliches and Reales. (English does not offer these distinctions, a sample of the imposing difficulties Lewis had to contend with.) For Hohl, Wirkliches is the real of everyday life. Reales is discovered in our fleeting intimations of the inexpressible, moments when we experience transcendent insights via encounters with art that are of utmost significance to us. But the Real cannot be accessed all the time, our experience of it is fragmentary. From this follows Hohl’s deep belief in the fragmentary nature of being, and this is what might have led him to use the note as a form in which to communicate. Notes inevitably tap into this vision of disjointedness. Hohl never wrote a treatise on Non-premature Reconciliation: he explicated the concept by way of several notes and over the course of several books. He takes this same accumulative approach to constructing all of his main ideas.

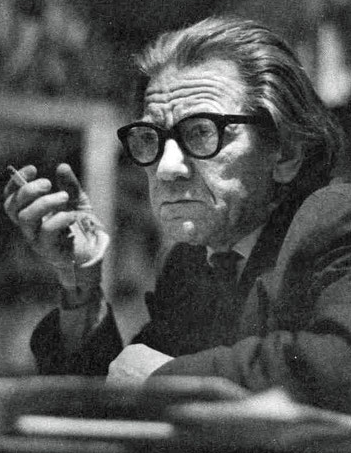

Swiss writer Ludwig Hohl. Photo: Prabook

Which brings us to why this translation is problematic; it commits the crime of abridgement. This is particularly tragic because Lewis is such an amazingly congenial translator. In the original German, The Notes consists of not quite 1100 notes. The Yale University Press volume has a bit more than 800 notes — so just under a quarter of the notes have been omitted. That means about a third of the original text is missing. (Generally, most of the longer notes have been cut.) Of the 12 chapters here, only the first is complete. In her introduction, Lewis confesses that she was reluctant to abridge The Notes. She decided to omit the notes that she felt were outdated in order not to harm the central theses of the book about art and life. Missing are mainly those notes that discuss Hohl’s negative experiences with the Dutch along with his considerations of dialect or obscure Swiss writers. However, there are more serious omissions — for instance, a number of notes in which Hohl explicates the nature of the fragmentary are gone as well.

The abridgement raises other uncomfortable issues. First, this is (ironically) a repeat injury to Hohl’s oeuvre. When the writer wanted to initially publish The Notes, his then-publisher only published half of the text. Hohl sued, and this landmark case would eventually strengthen the rights of authors. A decade later, the second half of the volume was published. Second, these omissions might well lead to misinterpretations of Hohl’s thought. For example, George Steiner states in Grammars of Creation, his 1990 Gifford Lectures, that Hohl views communicating with others as ancillary: “Communication with others is a secondary, almost unavoidably suspect function.” In fact, Hohl’s views are quite the opposite: to him, communication is always life-affirming and essential. While some of the notes dealing with communication and life-affirmation have been preserved in this translation, it must be noted that Hohl’s most extensive note, which contains his most detailed explication of these issues, has been left out, and that is a shame because that excision may lead to a limited understanding of one of his most fundamental ideas.

That said, this translation, abridged as it is, is a wonder. Better to have Hohl incomplete, reminding us through his fragments of what makes life meaningful, than to not have any Hohl at all.

Alexandra Sattler wrote the first English language PhD thesis on Ludwig Hohl.

Tagged: Ludwig Hohl, Tess Lewis, The Notes, translation

A thoughtful, deeply informed review of a writer whose work I only know peripherally. Now I’ll take a closer look. Many thanks