Visual Arts Review: “Fabrics of a Nation — American Quilt Stories”

By Chloe Pingeon

The quilts serve as landmarks whose significance is evolving with shifting times and demographics. Where have we come from, they ask. Where are we going? The answers are no longer what they were.

Harriet Powers’ Pictorial Quilt.

In the entryway of Fabrics of a Nation: American Quilt Stories (through January 17, 2022, at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts), a video loop displaying the show’s quilts is projected on a gallery wall. The images are in constant animation. Layered on top of one another, they fade in and out, outlined in computer-generated neon. In this electronic form, the quilts seem to become almost fluid, their images shapeshifting, their subjects and designs blurring together. Or do they lose their meaning entirely? It’s hard to tell.

It’s a provocative choice for an exhibition that is deeply rooted in tradition. Inside, the show’s seven gallery halls showcase over 50 quilts and textiles spanning 300 years. The quilts hang in quiet. They are still. Their histories are steadfastly woven into their threads by the many hands who have created and handled them. The density of tradition is infused into their fibers. This contrast with the motion of the technicolor projection on the entryway wall could not be missed. On the opposite wall, there is a quote:

“When people think of quilts, they think about warmth and security. So they can be kind of a soft landing — a way to tell the story of difficult topics.” — Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi

In light of Mazloomi’s words, the vibrant animation on the wall begins to make sense. Perhaps the quilts on display serve as a soft landing. But, once safely on the ground, viewers are invited to explore what they see in fresh ways. In the animation, the quilts’ designs and motifs merge into new combinations. Inside the galleries, the quilts are static, but the stories they tell are in constant motion. The story of the hands that made one textile takes on new significance when information about who owned the textile sits beside it. Narratives merge: the story of an enslaved individual who helped make one quilt is juxtaposed with the efforts of a contemporary artist who uses quilting to spread messages of social justice. The past and present are woven into the cloth, a fusion that reflects a complex and diverse American experience.

The galleries of Fabrics of a Nation are arranged thematically into seven sections, The textiles are ordered in a loosely chronological fashion. Still, the eye is immediately drawn to a contemporary piece: Bisa Butler’s To God and Truth (2019).

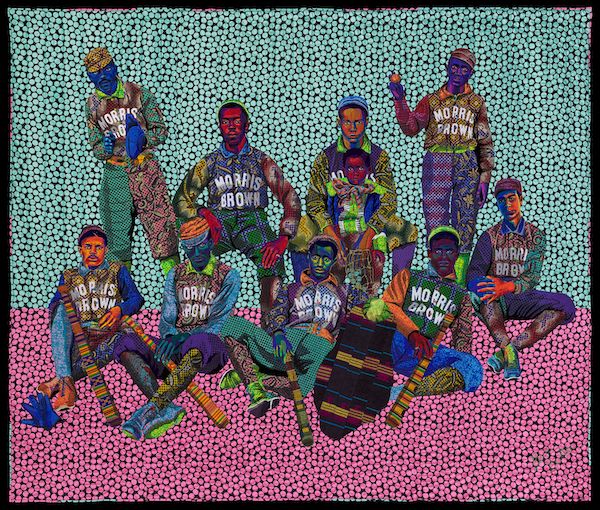

Contrasted against a bright pink and blue background, this quilt depicts 10 African American men who are wearing baseball uniforms and staring steadfastly ahead. The textile is based on an 1899 photograph of the baseball team of the Morris Brown College, among the first colleges in this country to be established by and for African Americans. The photograph is small, but the quilt transforms the men into distinctive individuals, slightly larger-than-life figures whose strength celebrates their humanity.

The title of this gallery poses a problematic question: WHO/WHAT IS AMERICA? The Butler textile provides at least one answer. The nation is the Morris Brown College baseball team. Hanging at the front of the exhibition, in front of numerous quilts some made by enslaved people, others depicting racist or bigoted images, this proud assertion takes on immense power.

The second gallery is titled UNSEEN HANDS. It is an acknowledgment of the stories that are hidden within the quilts. Ownership of 17th- and 18th-century quilts has been recorded, but the hands of the people who harvested the material for the fabric, the hands that wove the textiles, and the names of those who cared for the quilts remain unknown. One quilt in this gallery stands out because of the depth of its blue. It is titled, simply, Whole Cloth Quilt. The provenance of this 17th-century piece is mysterious, but the indigo color could only have been derived from harvesting the indigo plant, which relied on labor from enslaved people. In this show, the contributions of the silenced are highlighted. In the process, the quilt’s sublime beauty and its dark history are interwoven. How should we react? Should we feel guilt? Are we complicit?

Bisa Butler’s To God and Truth.

The exhibition’s next galleries take the visitor through American history.

The CRAFTING A NATION section displays quilts from the first half of the 17th century, largely focusing on the Revolutionary War. This gallery draws on what would make up a traditional American Quilt show but goes on to tell a more complete American origin story that includes the representation of indigenous people.

The CONFLICT WITHOUT RESOLUTION section probes the Civil War era, presenting images of division, conflict, and the Jim Crow South. A small contemporary quilt, Michael Thorpe’s Untitled, is embroidered with the words BLACK MAN, and serves as a reminder that racism and violence remain issues today.

The QUILT AS ART gallery represents the transition from textiles as a purely decorative form to textiles as art.

The MODERN MYTHS section displays works from the early 20th century. The traditions represented in these quilts reflect a diverse range of cultures and immigrants. The idea here is to falsify the myth that quilts are a fundamentally American art form.

The gallery titled MAKING A DIFFERENCE is the show’s most expansive. Here, the space opens and the walls are painted a crisp white — in direct contrast to the deep black walls of most the other galleries. The pieces here are about transition: they are about looking forward. There is irony here, asking that what has been seen as a conventionally “domestic” art form contribute to the future. And does it make sense to demand images of social change in an exhibition that displays work rooted in racism and violence? This disjunction seems to be the point. In order to move past the older quilts, their stories of racism, injustice, and historical erasure must be faced.

A colorful cloth globe, Virginia Jacobs’s Krakow Kabuki Waltz, stands in this gallery. In the artist’s words, the globe is a “changing view of a quilted form in space.” At its heart, Fabrics of a Nation examines the possibilities for transformation: changes in our ideas about the connections between tradition and art, in whose story is being told, and in what that story means. The quilts serve as landmarks whose significance is evolving with shifting times and demographics. Where have we come from, they ask. Where are we going? The answers are no longer what they were.

Chloe Pingeon is a rising senior at Boston College studying film and journalism. She has written regularly for the features and arts section of Boston College’s Independent Student Newspaper The Heights, and has also written for the culture section of Lithium Magazine. She is currently a creative development intern at Foundation Films.

Tagged: America Quilt Stories, Fabrics of a Nation, Fabrics of a Nation: American Quilt Stories