Film Review: “Algren” – (First-rate writer from the Second City)

By Ed Symkus

Once celebrated, but now largely forgotten, novelist and short story writer Nelson Algren deserves the attention given to him in a wide-ranging documentary.

Algren is available digitally through a number of cinemas. For a complete guide, go here.

Writer Nelson Algren. Wiki Common

Anyone familiar with the writings of Chicago native Nelson Algren (1909-1981) will want to see this illuminating documentary, which has been shelved since limited festival play in 2014. It isn’t a be-all, end-all biographical take on him. It’s more of a fan letter on film, along with a look at some of his personal history and a great deal of insight into his work.

If you’re unaware of what he could do with words on a page, treat yourself, for starters, to a reading of his 1956 novel A Walk on the Wild Side or his 1947 short story “Kingdom City to Cairo” (from the collection The Neon Wilderness). Either one will whet your appetite for what’s in store in Algren.

Filmmaker Michael Caplan packs a lot of information and opining into 86 minutes. A parade of talking heads, including novelists Russell Banks and Barry Gifford, film directors William Friedkin and John Sayles, and musicians Billy Corgan and Wayne Kramer, chatter in glowing terms of Algren the writer but, along with sharing an obvious fondness for him, aren’t afraid to dip into a few warts-and-all musings on Algren the man. Along with them are reminiscences of renowned photographer Art Shay, who was a close friend of Algren, and managed to chronicle much of his life and dealings with people of the streets with his still camera. Many of those haunting shots are peppered throughout the film.

But Caplan’s shining moments as a documentarian are the inclusion of sound bites of Algren reading from and discussing his prose, and footage of him in his later years being interviewed by an ambitious but green journalist who is unable to get straight answers to some personal questions.

So, who was Algren? He comes from a middle-class Chicago family. He studied journalism but couldn’t land a job, so started bumming around the country. His first short story, “So Help Me,” published in 1933, won an O. Henry Award in 1935. In the late ’30s, as a staff member of the left-leaning experimental New Anvil magazine, he hung out in bars in some of Chicago’s more sordid areas, where he interviewed patrons and prostitutes and — in his words — “My work there revealed a new way of writing for me.” He did a stint in the army as a private near the end of WWII and, returning to Chicago, he regularly went to taverns and listened to people there in order to get their voices down.

Those people and their voices led him toward writing about the downtrodden, the denizens who made up the less fortunate of Chicago. Russell Banks, in the film, says, “He didn’t look at them through a microscope; he embraced them, put his arms around them.” Billy Corgan, a Chicagoan and Smashing Pumpkins frontman, talking about Algren’s drunks and drug addicts and wife beaters and crazy people who “grew up in an industrial class that gave them no hope,” says of him, “He captures the beauty in that class, without judgment.”

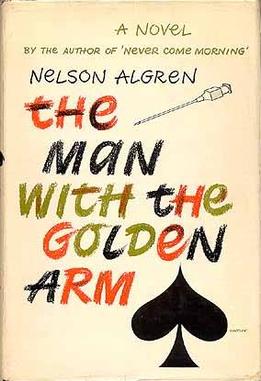

Wayne Kramer, guitarist for the MC5 — and composer of the jazzy-bluesy Algren soundtrack — talks about how his own drug addiction led him to Algren’s writing, specifically to his celebrated 1949 novel The Man with the Golden Arm. It won the first National Book Award and was adapted into Otto Preminger’s 1955 film, starring Frank Sinatra as junkie card dealer Frankie Machine.

Wayne Kramer, guitarist for the MC5 — and composer of the jazzy-bluesy Algren soundtrack — talks about how his own drug addiction led him to Algren’s writing, specifically to his celebrated 1949 novel The Man with the Golden Arm. It won the first National Book Award and was adapted into Otto Preminger’s 1955 film, starring Frank Sinatra as junkie card dealer Frankie Machine.

Though Sinatra was Oscar-nominated, Algren was not a fan of the film. In a sound clip, he says, “The book was written out of respect for these [broken] people. Preminger had contempt for these people.” John Sayles explains, “What Hollywood does to stories like that is shave all the edges off, and the stories don’t work without edges.”

Algren works well as a portrait of the writer, but some segments go on a bit too long. There’s much more than enough on his predilection for fashioning collages out of photos, letters, and newspaper clippings, and hanging them all over his cramped, messy, hoarder-like apartment; and the constant references to his longtime affair with French writer-philosopher Simone de Beauvoir — while she was still living with her lover Jean-Paul Sartre — are initially fascinating, but wear out their welcome.

An unexpected mention of Algren’s “funny side” addresses his habit of visiting Chicago’s improvisational nightclub The Second City, where he would sometimes get up onstage during a sketch and start sweeping the floor. But the film’s attempt at whimsy with its revelation of Algren’s “3 Rules of Life” — one of them, in an Algren sound clip is, “It’s never wise to eat at any place called Mom’s” — falls flat.

Algren became a literary celebrity, but he tried his best to remain what he thought of as the common man. He got great reviews and lots of people read him. Then they stopped. He eventually turned from fiction to travel pieces, political essays, and book reviews. After health issues began to get the best of him, his spirits were revived by news that he was to be admitted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Alas, the health issues won out.

So, again, who was Nelson Algren? He was an intellectual, a ladies’ man, a gifted natural writer, and someone who spoke up concerning social issues and stuck up for the underdog. He wrote stories of life’s losers, but he humanized them. The film touches on all of that. But if you want to get a more exacting picture, you should read his work.

Ed Symkus has been reviewing films and writing about the arts since 1975. A Boston native and Emerson College graduate, he co-wrote the book Wrestle Radio, USA: Grapplers Speak, went to Woodstock, collects novels by Harry Crews, Sax Rohmer, and John Wyndham, and has visited the Outer Hebrides, the Lofoten Islands, Anglesey, Mykonos, the Azores, Catalina, Kangaroo Island, and the Isle of Capri with his wife Lisa.

His favorite movie is And Now My Love. His least favorite is Liquid Sky, which he is convinced gave him the flu. He can be seen for five seconds in The Witches of Eastwick, staring right at the camera, just like the assistant director told him not to do.

I happened to be reading a highly entertaining collection of essays and reviews by the underrated critic Leslie Fiedler, The Devil Gets His Due: The Uncollected Essays, and came across his take down of Algren in a 1956 review of A Walk on the Wild Side. Here is a section about an author Fiedler calls “almost a museum piece –the Last of the Proletarian Writers.”

“Algren is finally a political writer and a moralist, though his politics is largely sentiment and his morality pure corn. Behind his present account of New Orleans pimps and whores there is a point, a gin-soaked pill of bitter wisdom…. the climax of the novel is a little sermon in pseudo-popular prose that surely must represent Algren’s own point of view, since it is completely improbable in the mind of the character who presumably thinks it: ‘All I found was two kinds of people. Them that would rather live on the loser’s side of the street with the other losers than to win off by themselves; and them who want to be one of the winners even though the only way left for them to win was over them who was whipped.’

These are not, of course, ideas but sentimental indulgences — a refusal to see the very characters the author imagines or remembers except through a haze of forgiving tears.”

Hi Bill,

Perhaps Fiedler is underrated when it comes to other literary criticism, but when it comes to Algren, he and Norman Podhoretz did a particularly vicious job of attacking his politics in the Cold War Red Scare era. I’m not sure what that does to his rating – maybe gets him closer to the literary critic Mendoza Line? If you’d like to view a film that covers this issue among other reasons why Algren’s writing and career were squelched you can check out our film here:

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/nelsonalgren/153380948

If you’re in the Chicago area, the film will be aired on WTTW, our local PBS affiliate, on Friday October 8, at 9:30pm.

Best Regards,

Mark Blottner

Co-director/producer

Nelson Algren: The End Is Nothing, The Road Is All