Film Reviews: Documentaries at the Toronto International Film Festival — Cops and Kenny G

By David D’Arcy

Docs at the Toronto International Film Festival ranged from the topical to the historical to the cultural. Here are a few that you should try to see.

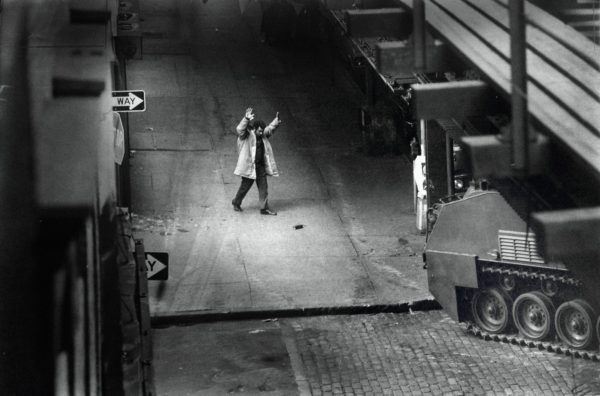

A scene from Hold Your Fire.

One of the docs that held my attention at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival revisited an attempted robbery in Brooklyn that led to a hostage-taking in 1973. One life was lost, but the standoff could have been much bloodier. It wasn’t, and that’s the point of the documentary Hold Your Fire, directed by Stefan Forbes.

Police held their fire, at least more than they were accustomed to. By NYPD standards, this pointed to a new way of reducing conflict.

On a Friday afternoon, four African-American men walked into an ordinary sporting goods store in Brooklyn. They wanted guns. When a policeman showed up, they shut the store and held 11 people there. Forty-seven hours later, they surrendered.

Please note that this was not the event that inspired the film Dog Day Afternoon (1975), a New York legend. That was a 14-hour siege after three men botched a bank robbery, also in Brooklyn, and held employees inside on a steamy August day in 1972, as a huge crowd watched it all.

In the same vein, Stanley Nelson’s doc, Attica, also at TIFF, about the 1971 prison uprising and its brutal suppression under orders from New York State Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, showed us how not to deal with hostage-takers. A total of 43 people died.

Hold Your Fire takes the 1973 siege apart, interviewing police, hostages, and the young Muslim hostage-takers, who served long prison terms. The film also introduces most of us to Harvey Schlossberg, a soft-spoken cop with a wry wit and advanced psychology degrees. Schlossberg, who died in May, was largely responsible for keeping the botched robbery from becoming a bloodbath.

This documentary operates on many levels. It’s a vivid crime scene story, with dark video footage of military-style police deployments enhanced by thoughtful reflections from five decades later on all sides. It’s a portrait of police, with insight into their strengths and weaknesses. It’s a chilling look at grim, dingy, wintry pre-gentrification Brooklyn – it could be the b-roll for The French Connection — brimming with character in its voices and faces, then and now. The massive elevated subway lines that frame the crime scene look like they were modeled after a dungeon by Piranesi. The film teaches a lesson in what can be gained when police are ordered not to react with violence, i.e., everything, Schlossberg says.

As always, the closer you look, the more facts emerge. The four young men who demanded guns at gunpoint made a stupid, irrevocable mistake. We hear as much from two of them in interviews. They could not even lift the heavy bag of guns that they wanted to steal. They were blamed for the death of a policeman, but it’s not known who shot the officer. Nor were the men members of the Black Liberation Army, as the press reported then.

By 1973, police had already learned enough about hostage-taking to keep the worst from happening. Yet the metaphor that tells you more about police relations with communities of color in New York, as one officer puts it in the film, is not a hostage negotiation, but an occupying army.

That army was held back in 1973 by commanders who knew, as Harvey Schlossberg says, that holding your fire is what negotiation is all about. Stefan Forbes’s probing documentary reminds us that, fifty years later, we’re still waiting for Schlossberg’s advice to filter down.

A scene from Listening to Kenny G.

The TIFF doc that surprised me the most was Listening to Kenny G, directed by Penny Lane. I have never liked Kenny Gs’ music — not in an elevator, not when I’m put on hold during a phone call, not even in Walmart. But this film forced me to appreciate Kenneth Bruce Gorelick for his honesty.

The world of film festivals is full of tribute films to artists. The TIFF program had just such a film about Dionne Warwick, a salute to the life of an important singer who helped expand the vocabulary of pop music. But like all in the genre, fully and dutifully reverent. Sundance is also full of such glorifying films. Listening to Kenny G is something different.

Director Lane, whose last movie, Hail Satan? (Arts Fuse review) suggested she might be doing something irreverent, is based on the premise that most respected and respectable critics don’t like the music of Kenny G, and with the assumption that those critics know what they’re talking about. I think they do.

That critical scorn is at the core of her film, just as Kenny’s commercial success is. Yet Kenny isn’t hiding behind a publicist. He’s game for addressing his detractors.

How often does a living artist agree to do that? How often does the catalogue for a museum exhibition of work by a living artist — or any artist — include a chapter or chapters by critics who criticize rather than celebrate that artist’s work? What popular or commercially successful artist would agree to that? Jeff Koons? Mel Gibson? Barbra Streisand? Madonna?

We watch as critics scratch their heads trying to find something positive to say, and fail to. Kenny’s fans (of all races) tell of their love for his music. Yes, his tunes are played at weddings. An African-American high school music teacher reminisces approvingly about a young man with a work ethic who’s accused of performing jazz-lite. Kenny himself talks about the disdain of his detractors. His explanation is that this is who he is. That still doesn’t make his music any more likeable for me. It does make him more likeable.

Kenny G, also a scratch golfer and a savvy investor, is critic-proof. We all knew this. So, by the way, are most hit movies and many best-selling authors. Disapproval doesn’t seem to bother Kenny or his fans. Eat your heart out.

A scene from The Devil’s Drivers.

The Devil’s Drivers, another doc at TIFF, is an action movie. The documentary is also a Sisyphean parable about the Israeli occupation of the West Bank of Palestine.

The filmmakers, Daniel Carsenty and Mohammed Abugeth, introduce us to young men in the Occupied Territories who drive passengers through gaps in the wall surrounding that area so they can work off the books in Israel. It’s very hard for unmarried Palestinian men to work legally in Israel, but it is a risk worth taking because the pay is many times higher than what they earn in the West Bank. They pay drivers to breach the wall and drive them to construction sites where Israelis hire them.

What we see is a mix of racing and bushwhacking as the Palestinian cars evade Israeli police and military vehicles. It works for the drivers and for the workers, until it doesn’t. We meet drivers who went to prison and who are now stuck in the failing Palestinian economy, banned from working in Israel, living on nickels and dimes.

The Devil’s Drivers can be exciting, like an overland roadless race. There’s real skill and courage in the way these men fly through the landscape, and there are the ultimate “fuck you” moments. (You can just imagine the “making of… doc.) These scenes might be a novelty for young viewers who never saw Smokey and the Bandit. But it’s hopeless. The Israelis, equipped with night vision and drones and faster vehicles, find and punish the drivers. They are shooting fish in a barrel, and when the men are caught the punishment is severe.

The filmmaking here will also remind you of high-speed chases in the COPS series, except that the dashcams are in the “criminals’” cars. You sense moments when the men feel free. But the economics are crushing: the drivers are shuttling workers to illegal jobs building houses for Israelis who will live at a higher standard than what all but a few Palestinians could hope for. One more thing. When the drivers are caught, as they all are, Israeli crews are sent to bulldoze their families’ houses. Sisyphus 2.0 ends up as a Demolition Derby.

The doc at TIFF that was farthest from conventional filmmaking is a repetition of three minutes of a home movie shot by a Polish-born Jew visiting his birthplace in Poland a year before the Nazis invaded.

A scene from Three Minutes – a Lengthening.

Three Minutes – a Lengthening, directed by Bianca Stigter and co-produced by the artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen, shows us film footage taken in 1938 by David Kurtz. It was found decades later in decay in Florida by his grandson, Glenn Kurtz. The film that we see, some of it in color, was shot in streets swarming with people, all Jews, who scramble to get in front of the camera.

Narrated by Helena Bonham Carter, the commentary heard over the repeating film clip describes the years of research by Glenn Kurtz to find out who the people in the frame are. A few of the 300 whom we see were alive after the war. Most were exterminated. In the town of 3000 Jews, only 100 survived. Kurtz provides a withering account of what he learned in the 2014 book, Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film.

There are no talking heads. Stigter keeps the focus on the people of Nasielsk, exuberant as they push and pull each other to get into the frame. As the tape repeats, we learn more and more about them. And we learn what was lost.

By replaying these images, Three Minutes – a Lengthening gives viewers no choice but to acknowledge all the vibrant lives that were lost. It’s a monument to those whom David Kurtz filmed in 1938 — and a reminder of the vast number of others whom we don’t see.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.