Jazz Album Review: “Merci Miles! Live at Vienne” — Of Historic as well as Musical Value

By Allen Michie

Davis solos less on Merci Miles than I wish he had, but he plays with precision, taste, and expression.

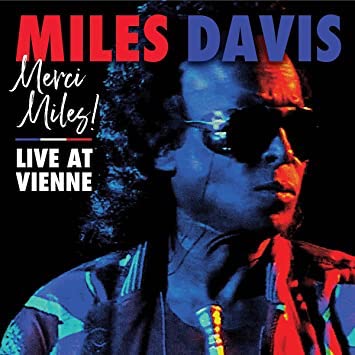

Miles Davis, Merci Miles! Live at Vienne (Warner/Rhino)

One of the great joys in a jazz lover’s life is to cut the shrink wrap and hear a record of new Miles Davis material for the first time. Adding to the pleasures so far this summer is Merci Miles! Live at Vienne, recorded live in France almost exactly 30 years ago on July 1, 1991.

One of the great joys in a jazz lover’s life is to cut the shrink wrap and hear a record of new Miles Davis material for the first time. Adding to the pleasures so far this summer is Merci Miles! Live at Vienne, recorded live in France almost exactly 30 years ago on July 1, 1991.

The two-CD or two-LP set has historic as well as musical value. The concert happened less than three months before Davis died on September 28, 1991. This was the last concert Davis played before the two surprising retrospective concerts in his final three months: the Montreux Jazz Festival concert with Quincy Jones on July 8, revisiting the music Davis recorded with Gil Evans, and the surprising all-star career retrospective hastily assembled in Paris just two days later on July 10. One day it would be great to have this entire short European tour — from June 28 in Hamburg to July 21 in Andernos, France — released as a compilation or box set. The Montreux concert with Jones conducting the Evans arrangements has been released as Miles and Quincy Live at Montreux (Warner), but the all-star concert has frustratingly never seen an official release (there is a poorly mastered bootleg CD out there named Black Devil). A nice touch in this future box set would be some speeches from the July 16 ceremony where Davis was awarded the highest honor in France, the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur.

No one seemed to think that Davis was close to death during these final three months. Davis kept his opinions to himself, but as many people do late in life, he was starting to pare things down. He was happiest with the simple pleasures of spending time and painting with his new partner, Jo Gelbard. His two career retrospective concerts in Montreux and Paris were motivated not by commercial interests, but by an apparently sincere wish to remind the world of his lasting contributions and to have reunions with the musical partners that meant the most to him over the years (including Evans, whom he claimed occasionally made ghostly visits).

Musically, Davis cut down his touring band from as many as 10 people to just five. Gone were the multiple keyboardists, guitarists, and percussionists. Merci Miles has a sextet — the same size as the band that recorded Kind of Blue. Gone were the racks of keyboard used by Robert Irving III and Adam Holzman in earlier ’80s bands. According to the new keyboardist Deron Johnson, “I didn’t have a big rig. I just had the basic materials needed. I tried to put more stuff into my playing than trying to just get every sound…. I had a sampler, which was cool, but basically it was one electric piano vibe, one synth, one organ. That was the great thing, though, because with that band there was just so much space.” The band members play less, and they play tighter. Even the stage-hungry guitar hero Foley was starting to chill: “We were at Venice airport one night and he told me to play half of what I normally played. It really fucked me up the whole day, and then I went on-stage and tried it, and I began to realize that’s what would make me phrase. That was the night I started to learn how to play.”

Davis solos less on Merci Miles than I wish he had, but he plays with precision, taste, and expression. Even if he is only stating the opening melody, he commands your full attention. With a little imagination, it’s not hard to aurally unplug the band on the opening choruses of “Amandla” or “Time After Time” and picture the early ’60s Miles Davis, in an Italian suit at a small NYC nightclub, playing his muted horn for a silenced audience. It’s striking to see the big picture of a dented and chipped Harmon mute on the front inside of the CD booklet or the LP sleeve — it’s a powerful reminder of the acoustic thread running from Miles’s earliest recordings to his very last, the low-tech tool that became so central to his distinctive voice on the trumpet. Perhaps Davis was thinking of his upcoming concert a week later when he would tackle selections from Porgy and Bess and Sketches of Spain. He may have been practicing on stage, as he insisted his band members always do, preparing to merge his contemporary sensibility with his old sound and phrasing.

There are newcomers here to freshen up the sound. Keyboardist Johnson, the last band member to be hired by Davis, has a jazzier sound than some of his more R&B-oriented predecessors. This is his first featured appearance on a Davis album, apart from a single track on the compilation Live Around the World. His solos often begin simply, then become increasingly harmonically abstract, sometimes skirting the edges of Herbie Hancock territory, as on “Hannibal” and “Amandla.” I suppose it’s easier to tour with a synthesizer than with a piano or a Hammond B3 organ, but when Johnson dials up those sounds, it’s difficult not to miss the real thing. Bassist Richard Patterson had been around since April 1990; he also appears on Live Around the World, but it’s good to hear more of his thick, popping, solid grooving on Merci Miles. He’s featured prominently in the mix, always to strong effect.

Those who’ve listened to many of these Davis concerts since 1987 may take Kenny Garrett for granted. There’s often a similar structure to his alto sax solos, a well-worn path he takes from his single-phrase beginnings — ones sometimes passed to him directly from Miles’s trumpet, his face close to the leader’s, and their instruments almost touching — to his percussive Maceo Parker-like middles and his dramatic late-Coltrane inspired finales. But he’s a fine player with his own sound and style: it’s impossible to think of these final Davis bands without him. He plays here as he always plays, with energy, passion, and individuality.

Foley, on a four-string “lead bass” tuned an octave higher, plays the rhythm guitar role high up on the fretboard. He’s all over “Wrinkle,” a draining workout for the rhythm section in dramatically shifting tempos. I have no idea why he doesn’t just pick up a guitar with strings — it would be much more forgiving given this funky style of rhythm playing. But hey, it’s his hands. Foley’s usual solo space is taken up on this night by Patterson (on real bass) and Johnson on keyboards.

Some writers have made much of the first appearance on record of two tracks written for Davis by Prince, the embarrassingly titled “Penetration” and “Jailbait.” I realize I’m an outlier here, and if Miles dug Prince then that’s cool with me, but neither of these sound like Prince put his back into it. “Penetration” strikes me as a non-jazz musician’s idea of what a jazz melody is supposed to sound like. It’s not much more than a riff, but it’s all the band needs to launch into the more rewarding solos as well as the red meat from Patterson’s funky bass. It’s a good foundation to set up a peak Garrett solo — he’s more abstract than you’d expect, and he starts with some phrases that wouldn’t sound out of place in a Wayne Shorter solo.

“Jailbait” is slinky and bluesy. The melody (such as it is, all three notes of it) hints at Henry Mancini’s “Peter Gunn Theme” but without the hook. It’s fundamentally a traditional 12-bar blues, and Johnson plays some Hammond B3 sounds on synth in that surging Gospel-influenced style. Garrett is an underrated blues player on alto (some smart Chicago guitarist should book him for a session). Still, “Jailbait” is a major lost opportunity — one of the great blues players in the history of the music was prowling around there on stage, and he didn’t take a solo. And this ended up being one of his last concerts.

“Amandla,” written for Davis by Marcus Miller, is a much better example of a song customized for the strengths of the player and his band. It’s an appealing and thoughtful melody with an interesting and complex set of harmonic changes. There are subtle syncopations in the rhythm that invite creative solos, and we get a fine one from Johnson (but again, alas, not from Davis). Davis has pared down “Amandla” to a ballad and transformed it into a fresh new song. It very gently swings in a few places, thanks to Ricky Wellman’s tasteful drumming, with its African feel intact.

Over the two CDs or LPs, Davis’s presence is more often felt than heard. But there are times when the Black Magus can still perform magic. The standout track on the album is Steve Porcaro and John Bettis’s “Human Nature,” famously recorded by Michael Jackson, which the Davis band had been playing at almost every gig since 1985. They ditch the overly familiar arrangement on this night and stretch it out to 18 minutes. It’s a marvel. “Human Nature” was traditionally the long Kenny Garrett feature on alto sax, and Garrett’s solo is still there, but Davis is the one who slays it. You can hear the classic Davis in how he states the melody — his playing is full of flexibility, style, and a fascinating sense of how elements of the melody can be disassembled and stacked up again in new combinations. There is some straight jazz playing, some extended notes to luxuriate in Davis’s muted sound, and beautiful cascading runs up and down and back up again. His famous silences separating his short phrases can bring the band (which is listening closely) down to a whisper. Davis stitches elements from the history of his styles into one long cohesive solo: there is a bit of the flamenco sound from Sketches of Spain and Siesta, some of the slightly spooky children’s melodies from “Jean Pierre,” and even a few bebop phrases. Sometimes it sounds like an aria, and sometimes like a human cry. He takes the mute out at the end of his solo for just two notes, and it gives chills.

Garrett plays to the rafters and screams it out for the crowd during his solo, abetted by the driving rhythm section. Between their two solos, Davis and Garrett don’t just play “Human Nature,” they portray it. Davis finds humanity subtle, melancholy, varied, and quizzical. Garrett agrees at first, then he argues for the darker, more stressed, nervous, and ferocious parts of us. The song ends cold after Garrett’s solo, because what could follow it? The crowd cheers, whistles, but Miles plays on behind it all, quietly and unaccompanied. He’s already begun setting up the next song, “Time After Time,” as if to say this is how human nature is, time after time.

Hearing this in Vienne on that July night in 1991, in a Roman amphitheater that has been in constant use since around 50 AD, must have been a powerful reminder of all that passes and all that endures.

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, TX. He has studied Miles Davis for years, is the moderator of the active Facebook group “Miles Davis Discussion,” and recently reviewed the Rubberband album for the Arts Fuse.

An excellent review, and I agree that the pared down band and sound are what add to the enjoyment of listening to this album. Good call on Deron Johnson — I thought he was a great addition to this band, and it’s a shame Miles didn’t live longer to explore the sonic possibilities of this line-up. Regarding Foley and his lead bass, I think he once said that six strings messed up his mind, hence the four-string approach!

The whole band was superb — Ricky Wellman was right in the pocket; Richard Patterson was fast, furious and funky, Foley played great rhythm as well as soloing, and Kenny Garrett was the perfect musical companion for Miles. I thought Miles played with great feeling on ‘Time After Time.”

I agree about the Prince tunes. They’re okay, but certainly no lost treasure. I love this album and your suggestion of a boxed set of gigs from this tour is a brilliant one!

Excellent review and foray through latter day Miles

Wonderful and thorough review, Allen. Makes me want to burrow into “Human Nature!”

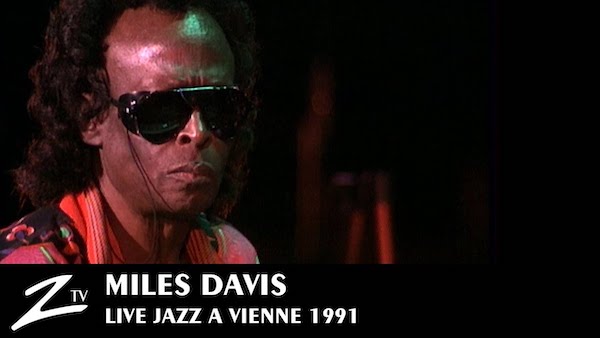

There’s a professional video of the “Human Nature” performance here:

https://youtu.be/VOpHgL52iUQ

Good review. Although he did a version of it, “Human Nature” is not a Michael Jackson song. It was written by Steve Porcaro and John Bettis.