Jazz Album Review: Barry Altschul’s 3Dom Factor — “Long Tall Sunshine”

By Michael Ullman

Long Tall Sunshine pulls off a delightful paradox: it combines in-your-face vigor with subtlety, probing free improvisations with appealing compositions.

Barry Altschul’s 3Dom Factor: Long Tall Sunshine (Not Two Records)

Although he had already appeared on valued recordings by Paul Bley and Chick Corea, I first heard the now 78-year-old drummer Barry Altschul live in the mid-’70s when he was with the then controversial Anthony Braxton quartet. The latter’s compositions, with their craggy outlines, abrupt stops and starts, and good-humored rhythmic quirkiness, posed distinctive challenges to the group’s musicians, but I would think particularly to the percussionist. Nonetheless, Altschul seemed to thrive in the Braxton quartet.

Braxton clearly appreciated Altschul’s talents as well: “Opus 23H” (Five Pieces, 1975, Arista) is an appealing piece which starts with a darting phrase that ends in a held note. That’s followed by a swirl upwards to yet another held note, then a lazy sounding phrase, which leads to a repeat of the original darting sound. The composed part of the piece continues in this quicksilver mode: part of Braxton’s strategy is to change the rhythmic feel, almost from measure to measure. The improvised part of the work is an Altschul solo. He plays a gong, and then seems to be making scraping noises on his cymbals. Soon he is playing all around his kit, jumping from tom-tom to snare and bass drum and cymbals and other instruments — yet in such a way that he seems to be shaping the silence. At this point, this listener can’t help but wonder why people found Braxton’s music so intimidating at the time. In the mid-’70s, Altschul was on a half dozen records that are now considered classics, including Dave Holland’s Conference of the Birds, Dave Liebman’s Drum Ode, Roswell Rudd’s Flexible Flyer, Sam Rivers’s Hues, and Julius Hemphill’s Coon Bid’ness. We can hear Altschul in the playful “Waltzing in the Sagebrush,” sung by Sheila Jordan on Flexible Flyer, and also on Chick Corea’s various versions of Wayne Shorter’s “Nefertiti.” The drummer was also part of Corea’s influential ’70s trio that recorded The Song of Singing and A.R.C. Everywhere, Altschul plays with rarely paralleled tact and delicacy.

The drummer proved he could also play with enormous force with the Sam Rivers trio, which is perhaps the closest among his recordings to the music produced by his 3Dom Trio. On Long Tall Sunshine he marries power to flexibility; the instrumental lineup features Joe Fonda on bass and Jon Irabagon on various reeds — tenor saxophone and alto clarinet on most of this disc. He also has a turn on the almost impossible to play soprillo saxophone, which is pitched an octave above the soprano. The sessions (some of the music was recorded live) are strikingly well recorded: closely miked and well balanced with enormous presence.

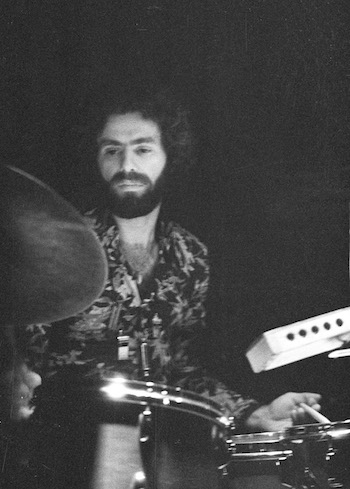

Drummer Barry Altschul in the mid-’70s. Photo: Michael Ullman

That presence fits the music. These are free or free-ish improvisations, all by Altschul, though they are sometimes based on a rather complicated (Braxton-like?) compositional approach. The title track begins with a repeated bass figure over drums. Then Irabagon states a pleasing melody; it’s singable, but it takes interesting turns and twists. For a brief moment, as the saxophonist begins to improvise, Fonda plays in 4/4, acknowledging the launch of a solo. Soon we realize that what we are really listening to is a group improvisation and a thrilling one: the rhythms, all vigorously stated, shift dramatically as Fonda and Irabagon embellish the pattern of Altschul’s composition. As I hear it, “The 3dom Factor” begins as a free improvisation: Altschul trusts his musicians in the same way that Braxton trusted him.

“Martin’s Stew” is the place where Altschul places his solo ideas. The track begins with a fascinating unaccompanied drum solo. Altschul uses all his kit, not as a dialogue among equals, as Max Roach would do, but to make a boldly unified statement. At one point he focuses on his hi-hat, moves to a quiet section on his cymbals, and then jumps to the tom-toms. The key to Altschul’s drumming seems to be its vision of inclusiveness, his brilliance at fashioning a coherent statement out of constantly shifting textures. Finally, Irabagon enters, stating the complicated melody. The saxophonist should also be praised for his agility; he is, like Fonda, confident and forthright and inventive, always ready to follow the rhythmic complexities being laid down by Fonda and Altschul.

On “Be Out S’Cool” Irabagon is amusing as well. The piece is made up of a kind of stop and start melody; at first, all three musicians play in a rough unison. Soon, though, Irabagon adds some quicksilver squeaks and squawks — it seems a kind of joke — before yielding to Fonda’s solo, his big-toned sound proffering some double stops. Irabagon returns on soprillo saxophone. He plays some lines in the high range that is natural to the instrument. You can’t imagine anything higher — the sonic antics include what sounds like the clucking of a cartoon chicken. Irabagon follows that with an occasional weird wail along with some more typical saxophone-like lines. Perhaps, for the sake of satiric contrast, Fonda at first decides to accompany the soprillo on bowed bass. He’s like a grumpy oldster complaining about a shrieky child.

On the other hand, “Irina” is a touching ballad whose theme statement is shared by Fonda and Irabagon on alto clarinet. The latter’s approach is unsentimental. At one point, he stages a fascinating conversation between the clarinet’s registers: he plays a keening statement high in the clarinet’s range and then answers that by hopping down to the instrument’s rich lower register. Things get wilder later on. Altschul remains a master drummer and bandleader. Long Tall Sunshine pulls off a delightful paradox: it combines in-your-face vigor with subtlety, probing free improvisations with appealing compositions.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: 3Dom Factor, Barry Altschul, Joe Fonda, Jon Irabagon, Long Tall Sunshine