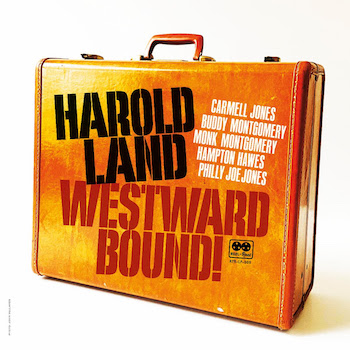

Jazz Album Review: “Harold Land: Westward Bound!”

By Steve Provizer

Saxophonist Harold Land has been a major contributor to the rich tapestry of jazz. Check him out.

Harold Land: Westward Bound! Available on CD and digitally as well as 33-1/3 RPM two-LP set on 180-gram vinyl. Deluxe package features new interviews with tenor giants Sonny Rollins and Joe Lovano and essays by Michael Cuscuna and pianist Eric Reed. (Reel to Real Recordings).

Jazz history is a dense and elaborately woven tapestry. Many listeners are familiar with the stars that glitter on the surface, but taking a deeper look into the fiber will disclose additional rewards. The truth is that, without the contributions of a cadre of lesser-known musicians, the cloth would look pretty threadbare.

Jazz history is a dense and elaborately woven tapestry. Many listeners are familiar with the stars that glitter on the surface, but taking a deeper look into the fiber will disclose additional rewards. The truth is that, without the contributions of a cadre of lesser-known musicians, the cloth would look pretty threadbare.

In terms of tenor saxophonists for example, most will know Coleman Hawkins, Sonny Rollins, and John Coltrane. But what about tenor players like Benny Golson, James Moody, Hank Mobley, Frank Foster, Lockjaw Davis, Teddy Edwards, or George Coleman? All these players established long, successful careers, both as sidemen and as leaders. They may not have spawned a large group of acolytes, but they were widely respected, made scores of recordings, and each developed a unique sound — the sine qua non of jazz.

Harold Land, leader of the three groups featured in Harold Land: Westward Bound!, is a player in this category. Although he is not particularly well known outside the infra jazz world, Land is as esteemed as any of his saxophone cohorts. If you don’t know his playing, it is my pleasure to introduce you to it.

And, as a bonus on this set, several songs feature Carmell Jones, a formidable trumpet player who also falls in the category of which I speak. The status of Jones among trumpeters was analogous to that of Land in the tenor sax world. Most will know the names Clifford Brown, Lee Morgan, and Freddy Hubbard. But the work of Blue Mitchell, Kenny Dorham, Idrees Sulieman, Bill Hardman, and Carmell Jones was equally respected. Jones’s highest profile gig may have been his stint with Horace Silver in 1964-65, including his performance on Silver’s album Song for My Father.

Land began to make a reputation in the late ’40s, and at that point he was very much under the sway of Lester Young. Through the early ’50s, he continued to develop his voice and in 1954 the great trumpeter Clifford Brown invited Land to join his quintet. This group became one of the most important of the era — it remains a jazz landmark. In 1955, in order to attend to family matters, Land decided to leave the group and go back to L.A. He was replaced by Sonny Rollins.

Land remained on the West Coast and continued in a stylistically similar vein throughout the rest of the ’50s. However, he was listening closely to John Coltrane and others who were stretching the music in fresh ways. He began to evolve in a new direction. Starting in the late ’60s, in collaborations with vibes player Bobby Hutcherson, drummer Billy Higgins, and pianist Stanley Cowell, among others, his playing demonstrated that he understood the newer sounds. He thoroughly integrated the modal approach into his earlier aesthetic, along with other musical elements. Land didn’t leap willy-nilly into the avant-garde. He expanded his musical horizons, while retaining his own voice.

It’s particularly interesting to hear Land’s playing during one stage of the process, between 1962 and 1965, when these recordings were made, live at the Penthouse in Seattle. I’ll go into more about the specifics of his transition as I look at each tune on Westward Bound!

The opening tune, “Vendetta,” is an up-tempo, intricate bop-type head written by Land. It’s based on rhythm changes but there’s some small Ornette-ish touches in the melody. Harmony rules here, and Land’s solo is consistent with his playing in the ’50s — it’s typically fluent and deeply knowledgeable of the changes. Carmell is also fluid and agile. His articulation is sharp and he hints at some chord substitutions. In some of the solo bridges, the rhythm section moves into a pedal tone for a few bars in order to vary things. Jimmy Lovelace, on drums, keeps everything together. This romp is in everyone’s wheelhouse.

The medium-up tune “Beep Durple,” based on “Deep Purple,” was written by Jones. It’s the kind of melody that Land and Clifford Brown might have played together. It’s hard not to hear the influence of Clifford in Carmell’s solo, especially in the vibrato. Jones shows that he is a player of the highest caliber, and Land’s solo is not far in quality from those he played with Brown. Land shows here that he’s taken in some of the 32nd-note scalar approaches pioneered by Coltrane. Buddy Montgomery on piano takes a few nice choruses and then drummer Jimmy Lovelace deftly trades 8’s with the horns and with bassist Monk Montgomery.

“Happily Dancing / Deep Harmonies Falling” is a Land composition — a waltz with an unusually insistent quality in the A section that transitions to a mellower feeling in the bridge. Although Land, Jones, and Montgomery on piano negotiate the changes, no one’s solo ventures all that deep. Perhaps this was a newish tune for the group.

The Rodgers and Hart standard “My Romance” follows. Pianist on this track is Hampton Hawes, another West Coast stalwart. Hawes and Montgomery on bass fashion an intro that slides easily into a statement of the melody. The latter is restated — in fairly straightforward fashion — in a medium-up tempo by Land, who then moves into his solo. I think there is some subtle Wayne Shorter influence here. Shorter was a distiller and retranslator of Coltrane and, at this point, to a lesser degree, so is Land. Nice Hawes piano and Montgomery bass solos. Land trades 8’s with drummer Mel Lee, who cranks up the energy until Land takes it out.

“Triplin’ the Groove,” written by Land, is a medium-up blues. Piano, sax, and drums all play the riff, sequentially, which probably explains the title. Heretofore, Land’s tone had nestled in the neighborhood of Hank Mobley and Teddy Edwards. But on this track we notice him adopting the harder tone that reflects the pervasive influence of Coltrane. It’s not as hard as it eventually becomes, but it’s on its way. Land’s treatment of the melody is recognizable, but he takes a different approach to phrase repetition. What emerges is a snapshot of a tenor player in transition. It’s an organic process; nothing tacked on for effect. Hawes on piano is given the opportunity to stretch and he displays a full range of techniques.

Harold Land at Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society, Half Moon Bay, CA, 1982. Photo: Brian McMillen

“Autumn Leaves” uses an opening bass/piano lick that sounds like it was adapted from the one on Cannonball Adderley’s 1958 record Somethin’ Else. Other rhythm section turns add some nice variations before Land solos. The tempo is perfect for Land, who doubles and triples the time several times during his solo. John Houston is in the piano chair and is more apt than Hawes to take off on right hand flights of fantasy. Philly Joe Jones is on drums and plays some blistering 8’s and then 4’s with the others before the out-chorus.

The Bricusse/Newley tune “Who Can I Turn To?” is the only ballad on the set. Houston on piano has the intro and Land states the melody with a breathy subtone, adding variations as he proceeds. He hands off to Houston, who turns in some effective phrases. Land finishes the chorus and closes the tune with an abbreviated solo tag ending — not a new idea in jazz, but Coltrane had made it a more widely adopted practice.

“Beau-ty” is a Carmell Jones composition. Philly Joe Jones starts off with a drum solo, leading the group into a repeated riff that has “Night in Tunisia” overtones. That moves into a Latin line in a minor mode. The bridge swings before the tune goes back to Latin and the soloists are backed by the rhythm section. Philly Joe uses a lot of low tom-tom, which gives the tune an Afro-Latin tinge. The track becomes a feature for drummer Jones and then there’s a return to the head and a frenetic finish.

Drums set up the Gillespie tune “Blue ‘N Boogie,” and the band goes full bore into an original intro before it puts a clever spin on a melody made famous by Diz and Bird. It’s surprising that the last tune in the set has no tenor solo.

Land’s work on this album stands by itself. However, if you want to have the added pleasure of being able to put these sessions into perspective, I suggest you listen to Land’s earliest, Lester Young influenced work. Then take in his terrific performances in the group with Clifford Brown. Finally, listen to the saxophonist’s late work on an album like Mapenzi or Xocia’s Dance. Land has been a major contributor to the rich tapestry of jazz. Check him out.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.