Jazz Album Review: Saxophonist Ivo Perelman and Pianist Matthew Shipp — Creating Potent, Laser-like Thoughts

By Michael Ullman

Ivo Perelman and Matthew Shipp’s duets will draw in and fascinate listeners who are open to intelligent, virtuosic, and intimate improvisations, simultaneously logical and free.

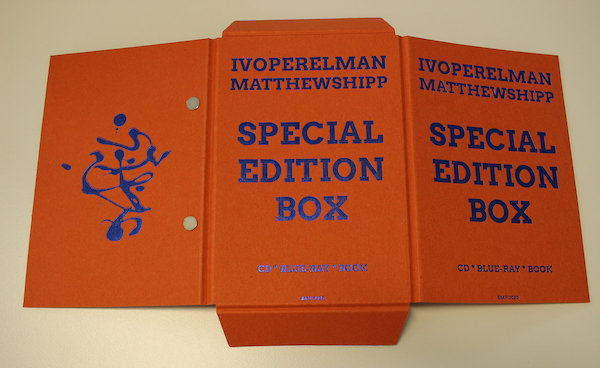

Ivo Perelman and Matthew Shipp: Embrace of the Souls and Live in São Paulo at SESC (Special Edition Box), SMP Records.

I am holding the small box, the size of a DVD case, presenting and celebrating the duets of pianist Matthew Shipp and Brazilian saxophonist Ivo Perelman. The package comes in three parts: a compact disc of 12 free improvisations the players call Procedural Language, which was recorded in January 2019; a Blue-ray disc called Live in São Paulo at SESC, which was filmed on July 11, 2019; and a 47-page booklet by Jean-Michel Van Schouwburg (translation by Andrew Castillo) that consists mainly of the author’s reviews of previous collaborations between Perelman and Shipp as well as sessions between those principals and others. (I’ve counted at least 17 Perelman-Shipp recordings.)

To my ears, jazz duets are particularly appealing. An interview I did with Keith Jarrett in 1992 makes my point. He was praising his one-time leader Miles Davis in an unexpected way. “He was,” Jarrett opined, “a listener. Essentially one of the best listeners I’ve ever worked with, whether he was a leader or not. His thing is hearing the music. His thing is not necessarily playing it. Hearing, I think that’s the essence of jazz.” If hearing is the essence of jazz, then the duet is a special gateway into that elemental value. In duets one can observe the players hear as well as play. Ideally, each player is simultaneously asserting him or herself and deferring to the other’s statements and retorts. It’s a kind of delicate dance, transparent and potentially illuminating.

The recorded collaborations between Shipp and Perelman go back to 1996 and the saxophonist’s Bendito of Santa Cruz. In the liner notes, Perelman explains their musical relationship: “When we play there is no ‘dominant character’ at play. The music dictates where we will go; it takes over and we manage always to leave our non-musical egos out of the equation.… Our ‘dominant character’ is nothing but a by-product of our ability to distill the many possible musical choices available at every turn of the way during the musical discourse into a potent, laser-like thought.”

I’ve heard free duets in which one musician makes a short statement, which is followed by a pause until the other responds. Perelman and Shipp don’t collaborate that way. Rather, it’s as if they simultaneously jump into the same stream: the music seems already in media res when they join in.

Pianist Matthew Shipp (l) and saxophonist Ivo Perelman (r). Photo: SMG Records

The Blu-ray disc gives us the two musicians spotlit on a darkened stage. The first piece begins with Perelman repeating, at different pitches, a downward-moving two-note phrase. Shipp enters immediately, with chords that I assume were not preplanned. What follows are interwoven series exercises in mutual self-expression and complicating adjustments. At one point, Shipp intensifies a series of thumping chords; Perelman counters with a high-pitched series of squeals. A movement up a scale (or something like a scale) by Perelman is typically a signal to Shipp to increase the tension. A squeal from Perelman, who is famous for his ability to play the highest ranges (and beyond) of his tenor, might elicit dark rumbling passages from Shipp, But then the pianist also has the option of letting the bottom fall out, suddenly playing pianissimo. They can counter each other or decide to team up and churn out rapidly darting lines. To viewers, it’s like listening to an excited conversation between people who can barely wait to agree…. or who just as cheerfully offer different viewpoints. Each musician also claims solo passages. In one of Perelman’s monologues, he hits on a little phrase that he then repeats, develops in a transparent way, and suddenly drops. A rhythmic phrase by Shipp, maybe a scurrying group of triplets, will suddenly resonate and seem to dominate the next few minutes of improvisation, though neither is playing that phrase exactly. For variety, well into a long improvisation, Shipp will pluck the strings of the piano or Perelman will temporarily blow squeaking sounds on his detached mouthpiece. Interestingly, the two rarely look at each other. Their conversation is purely auditory.

The Blu-ray disc captures one long, uninterrupted piece. The Perelman-Shipp CD is another matter. Its 12 numbered sections, all named “Procedural Language,” range from a little over two minutes to a little over seven. “Procedural Language 11” is the shortest: it’s performed rapidly by both instruments. After about 50 seconds, Shipp plays a rumbling passage that temporarily sounds like boogie-woogie, The piece seems to stop in mid-sentence. Numbers 8 and 12 share the same or similar theme, this time played by Perelman.

The clunkily written booklet appears to be largely cribbed from other Van Schouwburg projects. It is filled with puzzling non sequiturs. For example, “I was finishing up writing and translating a book on the music of Ivo Perelman and Matthew Shipp as a duo and their many albums.” There is no follow up to this sentence. Elsewhere, the author states mysteriously: “Our pianist’s approach, like Nina Simone, is syncretic, merging several practices.” We are told that Simone’s “approach” is similar to Shipp’s, but that’s all the analysis we get about the singer, except that the pianist heard her on TV. Van Schouwburg does one useful service: he supplies a list of the duo’s recordings. But no matter: the music is the thing that will draw in and fascinate listeners who are open to intelligent, virtuosic, and intimate improvisations, simultaneously logical and free.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Embrace of the Souls and Live in Sao Paulo at SESC, Ivo Perelman, Michael Shipp, Michael Ullman