Music Interview: Rickie Lee Jones on her Memoir and Living in the Present Tense

By Blake Maddux

“Then, as now, my focus was on the songs. As long as you can keep your focus on the art that you’re doing, the larger thing it can serve – selling records or whatever – that’ll happen on its own.”

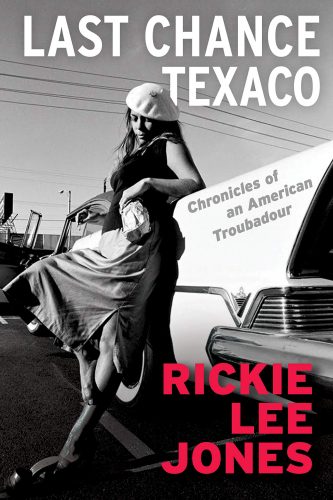

I usually use the space before a Q&A to introduce authors and give a short sketch of their most recent book. In this case, however, I need do nothing beyond linking to my Arts Fuse colleague Chelsea Spear’s eloquent review of Last Chance Texaco, the new memoir by singer, songwriter, musician, and self-described “American troubadour” Rickie Lee Jones.

Having appeared on The View and The New Yorker Radio Hour, the two-time Grammy winner and multi-time nominee will be the guest of Porter Square Books on Wednesday. Her interlocutor will be Doug Lockwood, a Boston Conservatory theater professor and author of Coolsville, a musical based on Rickie Lee Jones’s songs.

Amid all of this, Jones kindly found the time to speak to me by phone about her book.

Arts Fuse: How did it feel to recount so much of your life in such detail? Exhausting? Cathartic? Surreal?

Arts Fuse: How did it feel to recount so much of your life in such detail? Exhausting? Cathartic? Surreal?

Rickie Lee Jones: The question is a present tense question, because it’s still going on. It’s only been out for about a month. So it’s a process, and the process right now is seeing how people feel about it and then reacting to that. The first part was the writing of it and the next part was the releasing of it, and now it’s this part. I think that the writing of it was exhausting, sure, but I also was learning how to do something new. And I think whenever we learn a new thing, we become younger in a way. I was kind of Benjamin Button, going backwards. I’m very young now, and it’s weird. I feel all caught up to date and I don’t feel like I’m carrying the burden of those things. I feel like I honored my relatives. I feel like they are sitting there going, “Good job. We’re alright with what you did.”

I think the exhaustion came from being a disorganized person, so often trying to hand in a final manuscript became impossible, because it would somehow, like long hair, get tangled on its way to the post office. That was really frustrating. Or thinking that I wrote something better than it was the next day when I read it.

AF: Had you ever planned on one day telling your story in book form?

RLJ: I don’t know if telling my story was on the front of my mind if you’d asked me 20 years ago. So much of everybody’s story was so private. My mother wouldn’t have wanted me talking about my alcoholic father. Once they died, it began to seem possible, and once it’s possible, then the idea gets into your consciousness. So I don’t think that I always wanted to tell my story, but I always wanted to tell their story. (laughs)

AF: Did it start out as your idea or did someone suggest it to you?

RLJ: I did it all. They kinda thought they were just getting a rock memoir, I think. When I first had a meeting with them at their offices for them to help me edit it, they wanted to put in Saturday Night Live as the opening of the thing. And aside from how disrespectful that felt to the arc of the whole story, it somehow made all the stories negligible and incidental. The placement of everything is so crucial. So I said, “That’s not the book I’m writing”, and we didn’t talk much for a while. But now we’re best friends!

AF: What was more difficult: making it 350 pages long or limiting it to 350 pages?

RLJ: I had to edit it to that. It was definitely longer. It was hanging in at 380-410. I worked really hard to bring it down. What would keep happening is the epilogue (laughs) was sometimes 15 pages! Then it was one paragraph, and the editor said, “No, I really liked the other one.” I’m not good at endings in anything – lyrics, songs – and it took me the longest time to end the book. I looked at other memoirs to see what readers and editors tended to like. I really wanted to tell more, but I feel like psychologically that people don’t want to buy a book that is 420 pages. That was good for me, to have boundaries and constraints. It could have been War and Peace easily! A Tale of Two Cities or A Tale of Three Rickies! (laughs)

AF: Has anyone whom you mention in the book reached out to you to either contradict or embellish anything that you wrote?

RLJ: I did hear from [songwriting partner] Alfred Johnson, who at first was very worried that I said he had security clearance for his job. His head was spinning around. I’m gonna get him killed or something! After he read it, he saw that it was such a loving tribute and he was really happy. I really worked hard to bring Alfred into the book and tell you all about him. He finally called to say it was a very beautiful book and thanked me for what I said.

[After a few minutes of conversing about other things, Jones added] Oh, I did forget, Stephen Stills contacted me. His wife wrote a letter and said he’d like to thank me and loved the book. So I did hear from him. That’s pretty cool.

AF: You write about an incident in which a black friend’s assistant got pulled over while giving you a ride. In your retelling, he told you, “Please, put your hands on the dashboard where they can see them. They will shoot me if they wanna. Maybe you too.” Your reaction was, “I did not get my privilege, I got his exclusion … I felt the wave of racial hatred from the cops. It left a coating on my skin, but the Black man at my side had worn that skin all his life.”

RLJ: That’s right, and I got to feel exactly what that is. These are people who can and will kill you if you don’t act in a subservient way. It’s not just showing that you aren’t dangerous, but you better [say] “Yes sir, no sir.” I was in danger as well, just being in the car with the guy.

AF: That was in 1976. Your 1981 album Pirates included the song “Skeletons,”,which featured the lyrics, “And he goes for his wallet/And they thought he was going for a gun/And the cops blew Bird away.” What are your thoughts on the fact that innocent, unarmed black motorists are being killed on a regular basis in the same way that this man feared that he might have been 45 years earlier?

RLJ: I don’t know what to say. The good thing that’s happening is we’re talking about it. We’re still going through this initial phase of people wanting to know why their getting killed, or they were bad. “What was he doing before that?” To find a reason why it happened. There’s no reason for it. I’ll be glad when we exorcise this racist reaction, we white folks, of, “There must be a reason this policeman behaved badly.” So it’s exactly as it was except that we’re talking about it, and hopefully that will take us somewhere better. But it’s gonna take a lot of soul searching for all of us to find those pockets of racism that hide under, “Well, he was a criminal…” or whatever else people say.

AF: At a point in the book at which your album has been out for a while, you write, “A year ago…I only wanted to be a professional singer.” What did you envision that as being?

RLJ: I think what I was saying was that I wanted to be a professional musician, but maybe not a professional icon, and leader, and “the new voice of America.” But who imagines they’re going to be that? (laughs) Even if you wanted to, it’s not something we aim for as a vocation.

Luckily then, as now, my focus was on the songs. As long as you can keep your focus on the art that you’re doing, the larger thing it can serve – selling records or whatever – that’ll happen on its own. If you aim at that [selling records] instead of the song, then things go awry.

AF: The song “Last Chance Texaco” received a Grammy nomination for Best Female Rock Vocal Performance despite having not been released as a single. What did that feel like?

RLJ: At the time it just felt like I was really big, and I was the thing. So at the time, it just seemed like they are embracing me so much. And this song is so unusual in the family of people who vote that they just put it in there. It was extraordinary. “Chuck E.’s In Love” was a great song, but maybe by then they were already tired of it! [“Chuck E.’s In Love” was nominated for Song of the Year and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance]

AF: You occasionally mention praying to God, thanking God, and divine intervention. Are you religious, spiritual, both, or neither?

RLJ: I’m not a religious person at all, but I mention the invisible world a lot. I feel like we’re part of things that we can’t know, and part of things we can know but don’t yet. I have a feeling of being connected in ways that I understand emotionally or spiritually but will never get anybody else – nor should I – to understand how I interact with the invisible world, whatever you want to call that. I’m not a nihilist. I don’t really think religion serves a higher power. Religion helps human beings and helps them bond together and find comfort and community. But I don’t think the great invisible world can be written down. We can’t conceive of it, so we just gotta reckon that we’re part of each other and treat each other and ourselves with love.

AF: Let’s limit the answer to this last question to one word so as to not give too much away. Are you convinced that you rode with a real-life leprechaun on your way to see Van Morrison in Ireland?

Yes, yes, yes.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins–Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson–in Salem, Massachusetts.