Book Review: “Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South” — the Brilliance of OutKast

By Alex Szeptycki

Chronicling Stankonia is an engaging read, one that adroitly balances rigorous academic research with a deeply personal narrative about Black life and art in the post-Civil Rights Era in the South.

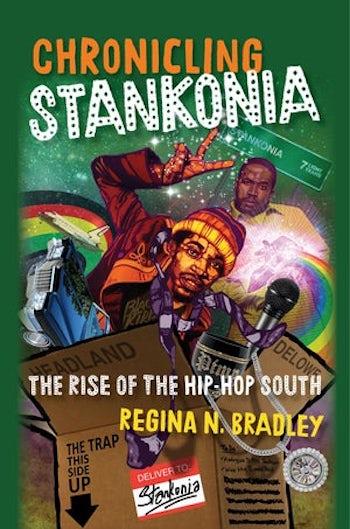

Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South by Regina N. Bradley. University of North Carolina Press, 136 pages, 19.95 (paperback).

“Ah, ha, hush that fuss/Everybody move to the back of the bus/Do you wanna bump and slump with us?/We the type of people make the club get crunk.” So say André Benjamin (aka André 3000) and Antoine Patton (aka Big Boi) of Atlanta rap duo OutKast on “Rosa Parks,” the lead single from their 1998 opus Aquemini. It’s simultaneously a call to action and a call to party, an invocation of an important civil rights leader set alongside some unapologetic youthful swag. The instrumental reflects the cultural/political mashup; OutKast had a habit of making music that could sound country-fried and cosmic at the same time, and “Rosa Parks” is no exception. The down home acoustic guitars mesh with kinetic, bouncy kicks and snare hits that echo throughout the mix.

“Ah, ha, hush that fuss/Everybody move to the back of the bus/Do you wanna bump and slump with us?/We the type of people make the club get crunk.” So say André Benjamin (aka André 3000) and Antoine Patton (aka Big Boi) of Atlanta rap duo OutKast on “Rosa Parks,” the lead single from their 1998 opus Aquemini. It’s simultaneously a call to action and a call to party, an invocation of an important civil rights leader set alongside some unapologetic youthful swag. The instrumental reflects the cultural/political mashup; OutKast had a habit of making music that could sound country-fried and cosmic at the same time, and “Rosa Parks” is no exception. The down home acoustic guitars mesh with kinetic, bouncy kicks and snare hits that echo throughout the mix.

Harmonious disjunction anchored OutKast’s mythology, and it is this tension that Regina N. Bradley explores in Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise of the Hip-Hop South. She examines the impact of OutKast’s pioneering of a new, Southern hip-hop that turned away from the New York versus Los Angeles dichotomy that had dominated the scene in the early ’90s. She then dissects the group’s work, showing its influence on other Southern Black narratives that she classifies under the banner of the “hip-hop South.” The result is a very engaging read, one that adroitly balances rigorous academic research with a deeply personal narrative about Black life and art in the post-Civil Rights Era in the South.

Bradley’s personal connection to the subject matter can be felt throughout the book. She lived in Albany, Georgia with her grandparents, who both participated tangentially in the Civil Rights Movement. Anecdotes told by her grandparents — as well as movement veterans who still lived in the area — fed the collective memory of her community.

Meanwhile, Southern hip-hop came to her by way of radio mixtapes, marching bands, and the subwoofers of passing cars. Artists like OutKast, Goodie Mob, Three Six Mafia, and Pastor Troy spoke to a young “Gina Mae” with a visceral power that remnants of the Civil Rights Movement couldn’t generate. In fact, these artists challenged the movement’s limitations because they addressed the visceral realities of Black life in Bradley’s contemporary South. As she puts it, “what Southern hip-hop realized and older generations wanted to tone down was that Dr. King’s mountaintop was not flat.” Hip-hop in the South was about pushing beyond complacency and memories — there was more to fight for.

OutKast was at the center of this volatile explosion of Southern hip-hop. At the 1995 Source Awards in Madison Square Garden, at a time the East Coast-West Coast feud that had been dominating hip-hop was at its height, OutKast won the Best New Artist award on the heels of their debut tape, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik. The New York crowd booed, but a young André 3000 fired back: “But it’s like this though, the South got somethin’ to say.” Bradley argues that this “is the genesis point for the hip-hop South…an incessant need to experiment with their Southern blackness and expand notions of the Black South.” OutKast’s took hip-hop in a new direction: the group was about portraying and interrogating Black life in the South.

The anecdotes that pepper the book nicely reinforce Bradley’s perspective. An examination of the construct of “the trap” in rap music is usefully supplemented by her memories of how listening to trap icon T.I.’s Urban Legend helped her mourn the death of her father. “[The music] didn’t need to be nice,” she writes. “The thump of the tracks, the adamant yet nihilistic affirmation of no fucks given that laced [T.I.’s] braggadocio and need to survive matched my own outlook on life at the time.” At another point, she probes the significance of the visual images OutKast created during its reunion tour. Bradley was at some of these concerts, and her firsthand experience gives her critical voice considerable vim and insight.

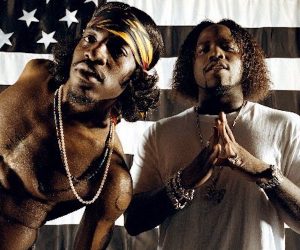

OutKast. Photo: @outkast

Chronicling Stankonia is split into four parts. The first section extensively breaks down the musical career of OutKast, starting with their debut record and incendiary Source Awards appearance and ending with their 2006 film and album Idlewild. In particular, her analysis of the duo’s sophomore album ATLiens captures a major aspect of OutKast’s magnetism: the space age futurism that they wove into their Southern roots. The album “moves far into the future to think through the implications of hip-hop and agency in the Post-Civil Rights South.” OutKast took its keen sense of a trauma-filled collective past and fused it with a future brimming with possibilities. This optimism grew to become a key element in their music as well as an influence on other Southern performers and artists.

Over the course of the final section of the book, Bradley connects OutKast’s music to other works of Black Southern art. She picks apart concepts like “the trap” and looks into how hip-hop has been used in modern day slave narratives, such as the film Django Unchained. Most compelling, however, is how she sizes up the similarities between Kiese Layman’s novel Long Division and Da Art of Storytellin’ (Part I and Part 2) from Aquemini. Bradley writes that the two narratives speak to the Black Southern experience in ways that balance temporal fluidity with questions of blackness, womanhood, and pain. She describes these artworks as providing “a messy benediction that disrupts the narrative of Southern Black stoicism as well as the act of healing as clean-cut and sterile.” They define the Southern Black experience for Bradley because they revel in the region’s tangled but beautiful complexity.

Evoking the majesty of OutKast’s artistry is a difficult task. The music of André and Big Boi was a world unto its own, so alien and strange that it is nearly impossible to describe its power and resonance. But Bradley evokes the spirit of their sound and its enduring vision, helped considerably by her life experiences as well as her meticulous research and attention to social context. Chronicling Stankonia not only establishes OutKast’s importance in the history of hip-hop, but the volume testifies to the enduring spell of its music.

Alex Szeptycki is a writer from Charlottesville, VA. He recently graduated from Stanford University, majoring in American Studies with a focus in contemporary art and pop culture. He’s currently working as a freelance writer at the Arts Fuse while navigating post-grad life in a pandemic.

Tagged: Alex Szeptycki, Chronicling Stankonia, Hip Hop