Book Review: “Endpapers: A Family Story of Books, War, Escape, and Home”

By Kai Maristed

Endpapers is an invaluable gift to literature, mainly but not only for the quotations, details, and beguilingly written scenes of publisher Kurt Wolff’s life scattered throughout

Endpapers: A Family Story of Books, War, Escape and Home by Alexander Wolff. Grove Atlantic, 360 pp., $26.

Alexander Wolff, a self-described child of suburban Rochester, NY, and summers in Vermont, had spent 36 years as a staff journalist for Sports Illustrated and authored nine sports-related books before he was bitten by something more than a twinge of curiosity about the tormented country and history that shaped both his grandfather and his father. I find this delayed awakening fascinating, like one of those rare clinical cases of someone waking from a decades-long coma. Once bitten, though, Wolff was, at age 60, completely engaged and energized by the task. He quit his job, gathering together family papers to be translated, and moved to Berlin for a first-hand rendezvous with the remnants of his family’s intersection with German history.

Alexander Wolff, a self-described child of suburban Rochester, NY, and summers in Vermont, had spent 36 years as a staff journalist for Sports Illustrated and authored nine sports-related books before he was bitten by something more than a twinge of curiosity about the tormented country and history that shaped both his grandfather and his father. I find this delayed awakening fascinating, like one of those rare clinical cases of someone waking from a decades-long coma. Once bitten, though, Wolff was, at age 60, completely engaged and energized by the task. He quit his job, gathering together family papers to be translated, and moved to Berlin for a first-hand rendezvous with the remnants of his family’s intersection with German history.

There is no lack of novels and memoirs about people who either perished in or escaped the Holocaust. While as varied as individual destinies, all these stories have narrative givens in common: fear, trembling, and suspense. For decades after WWII, this anxiety created an ethical chasm for certain writers and readers. What is speakable, what is unspeakable, and what is exploitation? Back in the early ’50s, the philosopher Theodor Adorno famously judged, “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” In context, by “poetry” he meant literature in a wide sense. Again Adorno: “When even genocide becomes cultural property in committed literature, it becomes easier to continue complying with the culture that gave rise to the murder.”

In our day books, movies, etc., are well past that sensibility. Perhaps it’s a good thing. Wolff, who came late in life to Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung (the work of processing the past) and is now a serious admirer of Germany’s collective effort to remember, would probably say so. After all, the risk of awed silence is forgetting.

Almost a century later, with the shelves full of Holocaust escape memoirs, it might be a challenge to find a publisher for another entry. But Wolff isn’t just any lucky (his own word) American descendant of resourceful, brave, and lucky survivors. He is the grandson of Kurt Wolff and step-grandson of Helen Wolff, the legendary publishing couple whose trailblazing support of brilliant, controversial writers, first in Germany and then in New York, helped shape the literary landscape we take for granted today. It’s those Wolffs who immediately drew me to read and review Endpapers: A Family Story of Books, War, Escape, and Home. People I know who have already ordered the volume also did so in anticipation of learning more about the lives of these, their heroes.

But that is not, by far, the author’s only project. As its full title suggests, Endpapers zigzags through a lot of territory. Wolff’s journalistic skills and meticulous, stubborn research have opened up fascinating historical veins surrounding and preceding his progenitors.

He lays out an illuminating history of the Merck family and fortunes, from its origins in the early 1800s as manufacturers of clinical grade opium (a best-seller) to the firm’s role in supplying Hitler with the cocktail of uppers and downers that kept him frantically prosecuting a war all around him saw as doomed. More distant relatives are called up, like Moritz von Haber, whose rise and fall in the service of German rulers exemplifies the golden era of assimilation epitomized by Frederick II, and the betrayal of hope and trust that followed. Other players include an illegitimate cousin, a jilted aunt, an aristocratic grandmother who corresponded with Himmler, a scurrilous Merck scion brought low, and quite a few more. (One of those old-fashioned genealogy tables would have been welcome.) I thrilled to have unexpected encounters with people I once knew, if only slightly: the redoubtable Gitta Sereny, Günter Grass.

Author Alexander Wolff. Photo: Facebook.

At the core of Endpapers, bracketed by Kurt and Alexander, stands a relatively modest figure, the author’s father. Niko Wolff, son of Kurt’s first wife, Elizabeth, remained sheltered during Hitler’s rise by the headmaster of his posh private school as a Mischling, a mixed Jew (Niko’s mother belonged to the Merck pharmaceuticals clan). Like his classmates, Niko joined the Hitler Youth and after graduation served in the Wehrmacht on both fronts. The ultimate team player? As a young man he comes across as a sort of 20th-century Candide, indifferent to and ignorant of Nazi perversity, instead writing home from the field about delicious, plentiful meals, blind to the starving peasants outside the German tents. His older sister wrote, “He is protected by his nature.” Only as war matured him and the tide turned against the Third Reich did the no longer well-nourished Niko revolt. “I was duped,” he wrote later. His father Klaus, already established in the USA, managed to secure Niko’s Atlantic passage as well as a graduate scholarship in chemistry at Princeton. He married happily, got his PhD, worked first for DuPont, then RCA, and voted as a “moderate, internationalist Republican.”

Endpapers contains anecdotes aplenty about this man whose “life has been a miracle” (Alexander’s last words to his father). For example, that he learned English by listening to the American Occupation’s jazz station. It is understandable that a son who scarcely asked questions until launching the project of this book, shortly before his father’s death, would compile what comes across as bits and pieces from multiple sources. The character of Niko Wolff remains a sketch, a line drawing without shadow, a mystery. Another abiding mystery is Alexander’s almost life-long lack of curiosity about Niko’s German past, or Germany per se — was it a sort of complicity, or filial identification, or protective instinct? The third mystery, to me at least, is that of inheritance — how is it that the two younger Wolffs, solid family men, each with his back to the past and looking only to the future, neither taking any active interest in literature or the arts, are direct descendants of the charismatic, unfaithful, temperamental, idealistic, risk-embracing, often outraged Kurt?

Kurt Wolff, born in Bonn in 1887, was very much recognizable as the son of a musician father whose circle included Brahms and Robert and Clara Schumann, and a mother who loved poetry and the works of Theodor Fontane. In his grandson’s words, “The Wolffs fixed themselves among that class of Germans known as Bildungsburgertum, the haute bourgeoisie that devoted themselves to Bildung, the life-long learning and a cultural patrimony of art, music, and books.” Kurt went on to study literature at Heidelberg and later Leipzig, the center of German publishing, with an adventurous interlude abroad as an intern in the banking business in São Paulo. Drawing upon a tidy legacy, he became a canny collector. “I loved books, especially beautiful books. But I knew I had to find a profession. What was left? You become a publisher.”

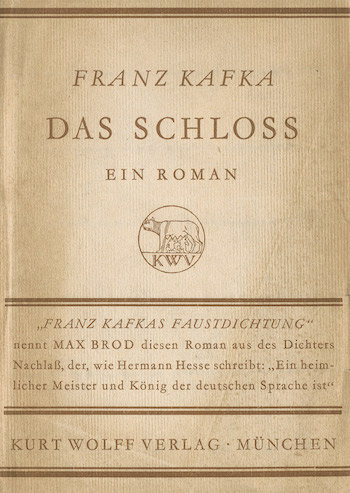

And what a publisher. He had something more than taste — an ability to sense the meaningful in the new, to separate the wheat from the chaff, even when the whole world was praising the chaff. At age 25 he hung out with Karl Kraus and Max Brod and published an awkward newcomer named Franz Kafka. Robert Musil. Heinrich Mann. Carl Sternheim. He paid well. It was hand to mouth for the firm until he published the little-known Rabindranath Tagore. The Nobel Prize for Tagore put the Wolff Verlag back in the black.

Not for long though. As WWI loomed his was the only major company to refuse to publish prowar literature. After he returned from the front, business never recovered completely. There was less public appetite for the avant-garde. Kurt himself fell into a long depression, selling off his collection bit by bit to keep staff paid. And then — Hitler. With his second wife and their child he escaped into France and, by the skin of his teeth and wits along with the help of selfless supporters, made it to the US. There, with Helen working at his side, the harried publishing phoenix rose from the ashes, to found Pantheon Press and introduce readers to a new wave of mostly European writers destined to form American minds and tastes for a long time to come.

Endpapers is an invaluable gift to literature, mainly but not only for the quotations, details, and beguilingly written scenes of Kurt Wolff’s life scattered throughout, between and betwixt accounts of other family members and ancestors. Less satisfying are Wolff’s takes on the history and character of a country about which he had almost no curiosity until, like Saul transforming into Paul, he moved to Berlin to write this book. Not at home in the language or the literature, he relies on the summaries of selected historians, notably Sebastian Haffner, whom he approvingly quotes as saying, “In animals it is called ‘breeding’…. something noble and steely, a reserve of pride, principle and dignity to be drawn on in the hour of trial. It is missing in the Germans. As a nation they are soft, unreliable, and without backbone.” One’s jaw drops, both at the nod to eugenics, and the silly blanket characterization.

Endpapers is an invaluable gift to literature, mainly but not only for the quotations, details, and beguilingly written scenes of Kurt Wolff’s life scattered throughout, between and betwixt accounts of other family members and ancestors. Less satisfying are Wolff’s takes on the history and character of a country about which he had almost no curiosity until, like Saul transforming into Paul, he moved to Berlin to write this book. Not at home in the language or the literature, he relies on the summaries of selected historians, notably Sebastian Haffner, whom he approvingly quotes as saying, “In animals it is called ‘breeding’…. something noble and steely, a reserve of pride, principle and dignity to be drawn on in the hour of trial. It is missing in the Germans. As a nation they are soft, unreliable, and without backbone.” One’s jaw drops, both at the nod to eugenics, and the silly blanket characterization.

Striking, too, is Wolff’s mocking animosity toward Bildungsburgertum. To blame a tradition that reveres the arts and humanities for blinding people to the magnitude of home-grown Fascism seems bizarrely misplaced. Hannah Arendt, among others, has pointed out that it was just this culture of Bildung, including the respect of non-Jews for Jewish music and art and letters, that for a time opened wide the doors to assimilation at the highest levels of society, wider than in any other European country. Would he rather everyone had played soccer?

History and family secrets, childhood resentments and emotions inevitably tend to become tangled up together. For all of Wolff’s acknowledgment of and pride in his grandfather’s stature, warmth is missing. Kurt emerges often as a roué, perhaps a narcissist, irresponsible toward kit and caboodle in his devotion to Art with capital A. Evelyn Waugh, in Brideshead Revisited, famously popularized the terms “Hearties” and “Aesthetes” to describe the antagonism between sports-loving, “well-adjusted” young men and those who lived on the fumes of poetry, etc. For all their achievements and loyalty, one senses such a mutual misregard among the Wolffs. Alexander Wolff set out in retirement eager to capture all the information he could about his family, and in the process to finally understand Germany. Shaping an enormous amount of source material into a fluently written and footnoted 360-page volume, he’s reached one goal, and generously shared with readers the journey toward another.

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other papers. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, set in Berlin. Recent fiction includes Evangeline, or Theories of Childhood Development, in The Iowa Review, and The Age of Migration, in Ploughshares Magazine. Read Kai’s Paris-centric take on politics and the arts here.

[…] Writing in the online cultural journal The Arts Fuse, critic and novelist Kai Maristed calls Endpapers “an invaluable gift to literature” that “[opens] up fascinating historical veins.” Read the review here. […]