Film Review: “Billie” — A Fascinating Spotlight on a Jazz Legend

By Allen Michie

Billie is a stunning new documentary about Billie Holiday, one of the greatest jazz vocalists of the 20th century.

Billie (Greenwich Entertainment. James Erskine, director and writer), streaming on Amazon.

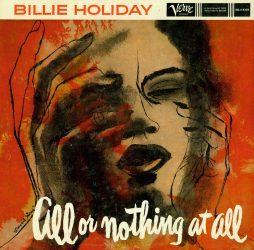

Billie Holiday in 1947. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Journalist Linda Kuehl, a white middle-class suburbanite, was deeply moved when she listened to a recording of jazz singer Billie Holiday in the early 1960s. Throughout the mid-’70s, she researched a new biography; her intention was to reverse the standard narrative that Holiday was a victim. Kuehl began interviewing dozens of people from across the full span of the vocalist’s life, building the story from primary sources. After Kuehl died unexpectedly in 1978, an apparent suicide, her tapes and notes were sold and used as the backbone for Julia Blackburn’s book With Billie. After that, the tapes remained obscure until documentary filmmaker James Erskine tracked them down. The result is the stunning new documentary Billie, available for streaming on Amazon (currently for only 99 cents).

Erskine’s hook is to make his documentary not just about the troubled life of Billie Holiday, which has been done many times before on the stage and screen. Billie is about both Holiday and Kuehl’s attempt to write a book about Holiday. Erskine has to walk a fine line: the stories of the two struggling women have to parallel, but it would be a huge miscalculation to suggest that the writer’s obstacles were at all comparable to Holiday’s. Erskine never claims a parity between the artistry or life struggles of the two women. Kuehl’s story is used instead as an example of how Holiday’s life inspires women to overcome sexism and to reach for career excellence. It’s also used to show how deeply Holiday’s music can get into people’s bloodstreams.

Erskine largely succeeds with the parallel stories, though Holiday’s striking history of sexual affairs (including Tallulah Bankhead) (Wait, what? Tallulah Bankhead!) tempts him into forcing the parallel, via a lurid and baseless rumor, about Kuehl and one of her famous interview subjects. At the film’s conclusion, Erskine speculates, irresponsibly, that there is a connection between this piece of gossip and Kuehl’s death. It’s an unfortunate end to what is otherwise a fascinating documentary, as well as a technological marvel.

One of the great contributions of Billie is the colorization of certain stills and film clips from the ’30s and ’40s. It’s an expensive and demanding process, so not everything here is colorized, but it’s a revelation to see what’s available. Other black-and-white clips, such as Holiday singing with Duke Ellington or Count Basie, are digitally restored with astonishing clarity and detail. You can’t take your eyes off Holiday.

The film begins quoting Kuehl’s statement that she didn’t want to portray Holiday as a victim. But any honest documentary can’t help but demonstrate otherwise, over and over again. Holiday fell victim to sociopathic abusers, drug addiction, and a relentlessly racist culture that made her enter through the kitchen while her white audiences came in through the front door. But Billie also poses an uncomfortable question. Several of the interview subjects repeatedly make the case that Holiday was a masochist — “she was only happy if she was unhappy,” as someone says. If so, then is it really fair to characterize her as a “victim”? Was her refusal to take control of the chaos in her personal life a matter of choice? When asked why jazz musicians so often die young (the interviewer was likely thinking of Charlie Parker, who died in 1955 at 35), Holiday responds, “The only way I can answer that question is we try to live one hundred days in one day.” Are those the words of a victim or a victor?

It is a predictable complaint in reviews of jazz films that too much attention is given to the Tragic Life Story cliché about musicians and not enough attention to what made their music great. Seeing as how this film has two life stories to tell in an hour and 38 minutes — and that Holiday’s story is genuinely tragic — it’s unrealistic to expect a musicological breakdown of her technique. Instead of listening to jazz critics and historians, we hear from Holiday’s friends and fellow musicians about how her music captivated them. The film is generous with footage of Holiday singing complete choruses and songs; in this way, her magnificent voice and expressive face speak for her artistry in ways that a scripted narrative never could. I defy anyone to need an explanation of “What’s the big deal about Billie Holiday?” after hearing her sing the entirety of “Strange Fruit” during her last filmed performance.

The film uses the familiar Ken Burns-style technique of slowly panning out from photographs during voice-overs. There is an artistic and effective use of typography over some frames, and there are staged set pieces (a glass of liquor on a table, a cigarette in an ashtray) to ground the film in our own time. Ironically, the beehive hairdos, polyester clothes, and house furnishings from the ’60s footage of Kuehl’s early life come off as more historically alien than the ball gowns and sharp suits from Holiday’s time in the ’40s and ’50s. The editing is masterful, and great attention is paid to transitions, both visual and narrative.

The film uses the familiar Ken Burns-style technique of slowly panning out from photographs during voice-overs. There is an artistic and effective use of typography over some frames, and there are staged set pieces (a glass of liquor on a table, a cigarette in an ashtray) to ground the film in our own time. Ironically, the beehive hairdos, polyester clothes, and house furnishings from the ’60s footage of Kuehl’s early life come off as more historically alien than the ball gowns and sharp suits from Holiday’s time in the ’40s and ’50s. The editing is masterful, and great attention is paid to transitions, both visual and narrative.

The interview tapes, often played with graphics of spinning tape recorders, are often jaw-dropping. This is no gauzy hagiography stuffed with celebrities paying tribute: the interviews were conducted in the early ’70s, when everyone remembered Holiday in life and feelings were still raw. There is an angry and bitterly resentful Jo Jones who demands to set the record straight about how Holiday was fired from the Basie band. Basie himself evades giving straight answers. Carmen McRae is testy and untrustful. No one can mention the name of Holiday’s last husband, Louis McKay, without saying they want to spit on the ground. There are interviews with the federal narcotics agents who tailed Holiday for her drug convictions. There are childhood friends, lawyers, and forgotten musicians who made those long bus rides with Holiday when she was the only Black member of the Artie Shaw band. We learn that Holiday’s own manager, Joe Glazer, tipped off the feds about Holiday’s drug use — he believed that a prison sentence was the only way to save her from herself.

Shortly before her death at 44 years old, consumed by her addictions, abuses, and disappointments, Holiday was a shadow of her former self. But when an interviewer asks her where she wants to be in the future, Holiday responds that she wants to be happily married, retire from singing, and start a home for orphaned children. I’ll let her go with that thought.

Allen Michie has graduate degrees in English Literature from Oxford University and Emory University. He works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas.