March Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Music

Jacqui Naylor’s voice merits your attention amid a crowded field of vocalists.

Many albums by female singers that arrive over the transom for review are pleasant but not distinctive. A recent exception: vocalist Jacqui Naylor’s The Long Game (Ruby Star). She has an attention-arresting, singular voice, pitched more or less in the range of Amy Winehouse. Naylor’s timbre contains a rich, almost buttery quality; she can dip smoothly into a low contralto range, drawing on the bluesy inflections and conversational style of Carmen McCrae.

Many albums by female singers that arrive over the transom for review are pleasant but not distinctive. A recent exception: vocalist Jacqui Naylor’s The Long Game (Ruby Star). She has an attention-arresting, singular voice, pitched more or less in the range of Amy Winehouse. Naylor’s timbre contains a rich, almost buttery quality; she can dip smoothly into a low contralto range, drawing on the bluesy inflections and conversational style of Carmen McCrae.

The album offers a few standards. The songs drawn from the rock repertoire are transformed into light rock, R&B, or country. The non-jazz tunes are not my thing, but Naylor is at home with all the material.

In Coldplay’s “Fix You,” Naylor does what she calls “acoustic smashing.” The tune isn’t all that compelling, but the rhythm section plays “It Never Entered My Mind” for accompaniment and that adds interest. Peter Gabriel’s “Don’t Give Up,” originally in 6/8 time, is mutated from a not-quite power ballad to a country-ish tune in 5/4 time. I’m not sure that Naylor’s breezy approach is right for David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” a tune that might call for a little more gravitas.

Naylor’s adroit treatment of the jazz tunes is where she stood out for me. She takes “Speak Low” in a sprightly clave that one seldom hears. Charlie Chaplin’s “Smile” is a song I’ve heard too many times but, to her credit, Naylor introduces the melody with just bass accompaniment and takes it in a snappy 6/8. This irons out some of the song’s soppy, cloyingness. Those who know “The Thrill Is Gone” from Chet Baker’s version may not recognize Naylor’s version. Rather than Baker’s lugubrious tempo, Naylor’s approach is up-tempo, which makes her take on the lyrics more appropriately distanced and less bathetic.

One wouldn’t purchase this CD on the basis of its instrumentals, but Art Khu on keyboards and guitar provides excellent accompaniment and solos decently. Jon Evans handles the bass chores well and Josh Jones plays whatever percussion style the tune calls for. In the end, with her controlled-but-conversational, blues-inflected contralto, adaptable to many genres, it’s Jacqui Naylor’s voice that merits your attention amid a crowded field of vocalists.

— Steve Provizer

Adam Sherman may not write and sing the happiest songs, but he’s not giving up the muse or the music, and that is something to celebrate.

A few weeks ago on SNL, they did a skit in the form of a talk show where the topic was: What in America still works? The punch line was that nothing still works in America (not the government, not the stock market, not the vaccine rollout) except for Tom Brady (played by John Krasinski).

A few weeks ago on SNL, they did a skit in the form of a talk show where the topic was: What in America still works? The punch line was that nothing still works in America (not the government, not the stock market, not the vaccine rollout) except for Tom Brady (played by John Krasinski).

Add Adam Sherman to the list of what still works. The Cambridge-based singer-songwriter-survivor has steadily refused to lie low during the lockdown. He released new singles almost monthly last year and did numerous virtual shows with Back Porch Carousel, a come-as-you-are collective comprising several other local artists who band together to raise money for area charities. Sherman’s new album, Triangle Sky, which was released on February 4, 2021, collects five of 2020’s singles (“Loveless Days” from February, “Downpour” from April, “Love Forgives” from May, “Justice Lies” from June, and “Self-Destructive Heart” from July), along with Back Porch Carousel’s “Currents,” written by him and released a week before “Love Forgives.”

To those six are added five other Sherman originals, all featuring his flannel voice and moving but melancholy songwriting. Two with particularly beautiful melodies are “Blank Slate” (“Give me a blank slate/Wipe away the pain/Let me feel the air I breathe”) and “Suffer Softly” (“I can’t embrace this solitude/I can’t erase the distance from you”). Those who heard “Justice Lies” when it was released last June will notice that on Triangle Sky it’s been given a more rocking backing track, with louder drums and and a wailing guitar solo.

The Back Porch Carousel tune, while featuring Sherman’s typically plaintive lyrics (“I know these thoughts are drowning me/Pain will pass like currents in the stream”), has a more rousing feel than most of the others thanks to extra vocalists and the collective talents of Sarah Levecque, Linda Viens, Randy Black, Peter Zarkadas, Matt Gruenberg, Larry Dersch, and Dana Colley. Joining Sherman on the rest of the tracks are his longtime collaborators Lauren Parks on cello, Chris Michaels on drums, and David Lieb on keyboards, as well as David Minehan on bass, Mike Levesque on drums, and Peter Zakardas on guitar. Dave Brophy (drums) and Joe McMahon (bass and piano) accompany Sherman on “Love Forgives.”

You can’t ask much more from an artist than to try to stay engaged in this lingering virus environment. Adam Sherman may not write and sing the happiest songs, but he’s not giving up the muse or the music, and that is something to celebrate. You can order Triangle Sky at the Adam Sherman Bandcamp site.

— Jason M Rubin

Richard Baratta has been executive producer on eight films, but he is also a musician with serious jazz chops.

There are way more entries for Richard Baratta in IMDb than on Allmusic. Baratta has been executive producer on eight films (including Joker and The Wolf of Wall Street) and production manager on 23 others (including five Spiderman movies). But like many other people with day jobs, from Hollywood producers to grocery baggers, Baratta is also a musician with serious jazz chops. He plays drums on Music in Film: The Reel Deal (Savant), a salute to some film music favorites worked up with straight-ahead acoustic jazz arrangements by pianist Bill O’Connell.

There are way more entries for Richard Baratta in IMDb than on Allmusic. Baratta has been executive producer on eight films (including Joker and The Wolf of Wall Street) and production manager on 23 others (including five Spiderman movies). But like many other people with day jobs, from Hollywood producers to grocery baggers, Baratta is also a musician with serious jazz chops. He plays drums on Music in Film: The Reel Deal (Savant), a salute to some film music favorites worked up with straight-ahead acoustic jazz arrangements by pianist Bill O’Connell.

The album features the great alto saxophonist Vincent Herring, who can sound so much like Cannonball Adderley that Nat Adderley had him in his band for nine years. This was a journeyman gig for Herring, but he brings energy and a vibrant creativity to this collection of 12 standards, could-be standards, and let’s-hope-not standards.

The album opens with “Everybody’s Talkin’,” a song used in Midnight Cowboy. The loping rhythm of Harry Nilsson’s original is exchanged for up-tempo swing, asserting Baratta’s jazz drummer credentials in the Art Blakey lineage. Another hard swinger is “Peter Gunn,” which lacks the twangy menace of Henry Mancini’s original — it sounds more like a Herbie Hancock session on Blue Note.

There are some fun discoveries, thanks to O’Connell’s creative arrangements. Nino Rota’s “Theme from The Godfather” is played as a waltz, and the minor turns in the melody and unusual chord changes provoke an imaginative solo from Herring. It’s certainly not very Godfathery, but it’s a jazz offer you can’t refuse.

Other tracks could have stayed on the cutting room floor. “Chopsticks” is here, I suppose, because of a memorable scene in the Tom Hanks movie Big. It’s an up-tempo samba here, and while O’Connell provides bright piano work, it’s a multicultural misfire. It’s even more disingenuous to include the Beatles’ “Come Together,” which isn’t a film song at all. O’Conner gives it a fast Latin arrangement, and the band finds a salsa groove hiding in there, lyrics be damned. Herring takes it like a pro, but there isn’t much to work with here outside of the rhythm. The same goes for “Let the River Run” from Working Girl. There’s not much to the melody, and all O’Connell is left with for his solo is some scales, patterns, and vamps. “The Sound of Music” stubbornly refuses to be jazz, because of its indelible pastoral associations as well as its lack of interesting changes. But students should check out how well Herring and O’Connell improvise strong melodic lines regardless of the source material.

Here’s hoping Baratta gets out of California and hits the live circuit after the final credits roll on this weird David Lynch movie we’re living in right now.

— Allen Michie lives in Austin, Texas, a city with few hills but nevertheless alive with the sound of music.

Vocalist Bruce Brown’s Death of Expertise breaks no new musical ground, but it understands the soil from which it has sprung.

Can what was hip in 1956 still qualify as hip? In this case, I say yes — even if the source of the hipness emanates from Wellington, New Zealand, home of singer Bruce Brown, who moved there from L.A. 20 years ago.

Can what was hip in 1956 still qualify as hip? In this case, I say yes — even if the source of the hipness emanates from Wellington, New Zealand, home of singer Bruce Brown, who moved there from L.A. 20 years ago.

On his new release Death of Expertise, Brown comes squarely out of the Chet Baker-Bob Dorough-Dave Frishberg school of vocalizing and songwriting (although Baker did not compose). He sings and does a bit of scatting in a pleasant tenor and the Bop, Latin, jazz waltz, and ballads he writes cover the gamut explored by his progenitors.

It is seldom that a song’s lyrics are interesting enough to earn my close attention. Brown’s lyrics can be sincere, à la Dorough, but they avoid the arch quality of Frishberg, which is a relief. Boasting some bons mots and inventive bits of word play, Brown’s lines are damn clever and work well with the music, which, on its own, is solid.

“I pulled my own teeth out, I replaced my own hip, just me and Dr. Google dishin’ out some safety tips — here’s to the Death of Expertise: I turned myself into my own best surgeon“

“Doreen, don’t mix tequila with chlorine — It’s time to give that tambourine a rest. Doreen, it’s time to take your thorazine.”

The message of “They’re Everywhere” is, perhaps, somewhat derrière garde — mixed, at the least. The sentiment is: women are everywhere and although men might be tempted to cross the line, they should not. Fair enough, but to say “ignore how they dress” is, well…

Two songs veer from Brown’s usual stance of slightly distanced observer. “Giving Up Is Not an Option” is a straightforward tune that delivers the title message. I half expected to have the rug pulled out from under me, but it didn’t happen. The other is “The Music Plays Again,” a tune with no ifs, ands, or buts to qualify its sweet romantic message.

Brown can play piano, but he has left the keyboard chores here to John Harkins. The other support includes Brendan Clarke, bass; Andrew Dickes, drums; Steve Brien, guitar; Steve Crum, trumpet and fluegelhorn; and Glen Berge, saxes and alto flutes. All are quality musicians who deliver efficient background and good solos.

Death of Expertise breaks no new musical ground, but it understands the soil from which it has sprung. Its lyrics bloom, releasing a heady whiff of originality.

— Steve Provizer

Books

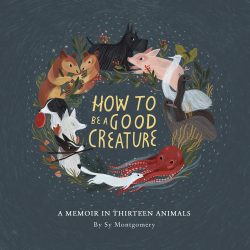

How to be a Good Creature explores what is becoming a new and evolving attitude toward animals — patronization is giving way to admiration

How to Be A Good Creature: A Memoir in Thirteen Animals by Sy Montgomery. 200 pages with illustrations. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $20.

Have we been looking at animals the wrong way? Author Sy Montgomery thinks so.

Have we been looking at animals the wrong way? Author Sy Montgomery thinks so.

For much of our history, animals have been thought of as sources of food or game or as pests. In recent years, science has “discovered” that many animals are sentient and even intelligent. This revelation has led to a reconsideration of the value of animals based on how close they are to being human. Koko the gorilla, for example, learned to use sign language and could teach other gorillas to sign. But, as we learn more about the complex society of bees, or the regenerative talents of octopi, a revolutionary shift in perception is taking place. How to Be a Good Creature explores what is becoming a new and evolving attitude toward animals — patronization is giving way to admiration

From this new perspective, animals are not valuable because they taste good or because they are almost as smart as us. They make invaluable contributions to existence. In this homage, Sy Montgomery delves into her experiences with 13 animals, including her four dogs, three emus, a pig, an octopus, and a few exotic creatures from Guyana. She finds that she is able to communicate with all of them. In fact, if she shows that she cares about them, they respond in kind. The emus show her where they secretly sleep and allow her to camp with them. An octopus grasps her hand with seeming affection. Her dogs bring her daily joy on walks and games of frisbee. Montgomery suggests that, when we try being “a good creature” to the animals, their and our worlds expand.

— Ed Meek

That dedication to conveying “this is it” — without any decoration, theoretical or otherwise — has made Ai Weiwei one of the most valuable visual artists of our time.

Conversations: Ai Weiwei, Columbia University Press, $19.95.

Conversations is made up of six public talks featuring the renowned artist and political dissident Ai Weiwei. They were held after the premiere of his massive 2017 New York City public arts project Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, which was presented in 300-plus sites across the metropolis. Ai’s epic, globe-trotting documentary about the mass immigration, Human Flow, had just been released. His latest documentary, 2020’s Cockroach (Arts Fuse review) is made up of you-are-there glimpses of the violent student protests against China’s ongoing police action in Hong Kong; the film’s images of brutal repression take on added prescient alarm given that, according to the February 28 New York Times, “Hong Kong authorities recently charged dozens of pro-democracy figures with violating the Chinese territory’s harsh new national security law, the latest blow to the dwindling hopes for democracy in the former British colony.”

Conversations is made up of six public talks featuring the renowned artist and political dissident Ai Weiwei. They were held after the premiere of his massive 2017 New York City public arts project Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, which was presented in 300-plus sites across the metropolis. Ai’s epic, globe-trotting documentary about the mass immigration, Human Flow, had just been released. His latest documentary, 2020’s Cockroach (Arts Fuse review) is made up of you-are-there glimpses of the violent student protests against China’s ongoing police action in Hong Kong; the film’s images of brutal repression take on added prescient alarm given that, according to the February 28 New York Times, “Hong Kong authorities recently charged dozens of pro-democracy figures with violating the Chinese territory’s harsh new national security law, the latest blow to the dwindling hopes for democracy in the former British colony.”

Despite the attempts of Ai’s interlocutors to draw large statements out of the artist about the future of China, the meaning of his work, and whether art can make change, he handily defeats their attempts via a sort of erratic (or is that cagey?) insouciance. Perhaps, after he was imprisoned in China for daring to speak freely, he is wary of circumscription, elitist or otherwise. He claims his public art is driven by an egalitarian impulse; he makes big statements via oversized works designed to generate a maximum amount of attention. He and his team pragmatically, efficiently, and economically create pieces that are calculated to engage people across class and ethnic lines. Ai is not interested in high-flown abstractions, is extremely wary of high-priced art schools (“Quit school and do some traveling. Go to areas you never imagined or dreamed of”), and is forthrightly anti-institutional. Here he is on MoMA: “You know MoMA is such a shitty place … they have too much money and have built fantastic buildings but shit is shown there. Sorry, I cannot control myself when I talk about those art institutions.”

We learn some about his relationship with his father, a celebrated poet forced to clean restrooms during the Cultural Revolution, his years as a bohemian in New York during the ’80s. But, for me, Ai is at his most compelling when he undercuts the unspoken assumption that — given his escape from China’s authoritarianism — he should celebrate the freedom he has in the West. To his credit, Ai points out that repression, and the well-heeled bureaucratic indifference to humanity that powers it, cuts across the globe. He can be amusing in making the contrast:

I come from a society where everything’s restricted. Everything. Suddenly, you come to a place where even if you were found dead in your apartment, nobody would care. You can call it freedom, but you can call it something else.

What Ai calls it, I think, is a tragic abdication of moral and political responsibility. At one point he condemns the United States, Britain, and France for selling hundreds of millions of dollars of arms to Saudi Arabia. This is a problem — stoking the machinery of death — that they could fix if they wished. And we all know it, but deny that we do.

Everybody knows weapons are made for killing, and everybody knows those weapons should not be sold to those kinds of societies. I think it’s an insult to our public and our intellect to think we don’t understand this, or are we just pretending not to know this. We just pretend that the consequences have nothing to do with us.

They [the countries] have been selfish, narrow-minded, and so corrupt. The whole society is corrupted. They just pretend we are not part of it. Come on. I don’t think we even need to talk about it. We’re all in deep shame.

That notion of “deep shame” is shocking — and refreshing. Ai doesn’t draw on the current panoply of “engaged art” vocabulary: empathy, empowerment, inspiration, knowing your own worth, etc. He sees his role to be a witness — art is about cutting through our self-destructive denial of reality. Ai makes his approach clear when he talks about one of his works, images of life preservers saved from Lesbos after Syrian refugees arrived:

If I can call something ugly, I would say those life jackets are very ugly. I usually don’t use that word , but you know, because so many people drowned in this ocean, because many of the jackets were fake and didn’t float. How can you illustrate those feelings? It’s very hard. You’re not decorating life, but you are instead saying, “Hey, this is it.”

That dedication to conveying “this is it” — without any decoration, theoretical or otherwise — has made Ai Weiwei one of the most valuable visual artists of our time.

(Note: In the course of making Human Flow, his documentary on the global refugee crisis, Ai Weiwei and his team interviewed more than 600 refugees, aid workers, politicians, activists, doctors, and local authorities in 23 countries around the world. Only a handful of these conversations made the film; the volume Human Flow (Princeton University Press, $29.95) features 100 of these interviews in their entirety. These diverse voices are forceful testaments to the catastrophic fallout of war and persecution. Another way that Ai conveys “this is it.”)

— Bill Marx

Film

A powerful cinematic vision of the crime of rape.

A scene from Test Pattern.

Test Pattern, screening at the Coolidge Corner Virtual Theater

Test Pattern is the debut feature of Shatara Michelle Ford, who, “frustrated with the ways in which we speak about assault,” wrote, produced, and directed a film about the aftermath of a rape. The casting of Brittany S. Hall and Will Brill as Renesha and Evan, an interracial couple, is surprising, and not only because of the racial dynamic. The characters are a study in contrast, physically mismatched. Renesha is beautiful, stylish, accomplished, and confident. Evan is awkward and rail-thin, a tattoo artist who dresses in a ripped white T-shirt. He approaches her outside of a club one night and asks for her phone number. Why does she agree? Before we know it, they appear to be living together. The starkly equivocal nature of the relationship is designed to keep viewers off-center. What do these two have in common? A liberal attitude, enhanced by an enthusiasm for sex, may be the easy answer, a fact that complicates the issue.

An unexpected assault avoids any element of exploitation and titillation. The legal and personal aftermath shapes most of the narrative. Because a rape victim has been coerced into a sexual situation, they need to control the consequences if they are to regain self-respect and autonomy. Instead, Renesha is confronted with bureaucratic coldness and indifference. She is faced with an apathetic health system and a misogynistic legal system that raises hostile questions about her personal responsibility.

Renesha also has to deal with the challenges of psychological trauma. Her disorientation and uncertainty shape what is at times a disjointed narrative. Sudden flashbacks alternate with extended moments of simmering frustration and anger. Ford dispenses with needless exposition and dialogue. Scenes are often composed off-center; we see figures at the edges of the frame. At times the score runs counter to dramatic content. Particularly troubling is the alienating use of Tchaikovsky’s “Waltz of the Flowers” from The Nutcracker Suite. The piece accompanies slow-motion scenes of Renesha and Evan as they attempt to procure a rape kit. Is this what’s going on in the woman’s mind? Directorial choices like these generate a subliminal tension, leading to an unsettling emotional ambiguity.

A test pattern is defined as “a transmitter which is active while no program is being broadcast.” It is an apt title for this film’s powerful vision of the crime of rape. It is an assault that demands attention, but often deliberately puts the victim on spirit-killing hold.

— Tim Jackson

Demonic possession meets influencer culture

A scene from The Cleansing Hour.

Like so many new horror films crowding the market these days, The Cleansing Hour (directed by Damien LeVeck) combines a provocative premise with tight production design. In addition, add this film to the growing list of intriguing new originals from streaming network Shudder. The network’s bread-and-butter is contemporary indie and low-budget horror, with some vintage classics, a few art-house gems, and plenty of low-brow schlock tossed in to sweeten the pot. Shudder hosts a livestream too, including weekly showings of The Last Drive In, which stars comedian and film critic Joe Bob Briggs (last week’s Valentine’s feature was The Love Witch). It’s a great network for horror buffs, given that its selections range over a number of subgenres including slashers, zombie flicks, folk horror, and movies about the occult.

The Cleansing Hour borrows conceits and elements from a number of different sources (including The Last Exorcism and the FOX series The Exorcist). But, at its heart, this is a fairly original story. Films about demonic possession are on the rise (a sign of our fearful times?). And they are increasingly crossing over with newer stylistic horror sub genres, such as found footage and fake documentaries (thanks to The Blair Witch Project). Possession can be portrayed in one of two ways: via extreme images of body horror that depict the ravages of the inhabiting demon or via psychological transformation, with the possessed host speaking, moving, and behaving in ways that suggest a demon is present. William Friedkin’s 1973 film The Exorcist dramatized the horrific changes in 12-year-old Regan’s body and voice (not to mention her behavior and vocabulary). 1990’s The Exorcist 3: Legion (directed by author William Peter Blatty) gave us Brad Dourif as a priest possessed by a possessed (yes, a double possession!) serial killer.

The Cleansing Hour is a valiant attempt to bring this genre to the TikTok generation. Max (Ryan Guzman) is a charismatic influencer who has crafted an elaborate scam. He claims to be a priest who is also a certified exorcist. His live video broadcast shows him exorcizing demons from people, with assistance from his tech wizard friend Drew (Kyle Gallner), who creates brilliant sound and visual effects to make the faux seem real. When Drew’s girlfriend Lane (Alix Angelis), an aspiring actress, volunteers to fill in on the show, things get weird after an actual demon takes over her body. Max and Drew are forced to improvise.

There was plenty of potential here to serve up an incisive commentary on the, well, rather evil nature of influencer culture, but the screenplay (co-written by the director with Aaron Horwitz) fails to pluck the low-hanging fruit of social satire. Still, The Cleansing Hour boasts masterful special effects — it is genuinely scary at times. The actors do a superb job, too. LeVeck might be a director worth keeping on eye on — if he decides to acknowledge that viewers might desire a bit more depth along with his clever plot devices.

— Peg Aloi

Television

The series provides a clue to what being governed by olfaction is like.

The Sniffer, a subtitled Russian television production (Netflix).

A still from The Sniffer.

The title character (Kirill Käro) has a prodigious sense of smell; bloodhounds would envy him. But unlike even the smartest dogs, he can ascertain and discuss the provenance of anything he smells — from a rare and expensive Japanese tea, brewed only out of topmost tea leaves, to the material used in a famous painting, which he authoritatively declares to be acrylic rather than oil and therefore nothing but a high-priced fraud. The Sniffer can smell dopamine, so he has inklings about your mood; he can also smell insulin, which tells him about your health. And if you drink too much the Sniffer will know by the shmek of your liver.

I’ve often wondered what it’s like to be an animal whose determining sense is not vision, as it is in our species, but olfaction, as is true of ants, for example. If you drop a massive beetle into an ant colony and douse it with the appropriate chemicals, the ants will not treat it as an alien invader even as it devours their larvae. Similarly, if you dose a healthy ant with the odors emitted by dead ants, that ant will be returned to the dead pile no matter how hard it strives to resume its usual duties. For more about ants and olfaction, see the work of E.O. Wilson, who has attended to it.

The Sniffer provides a clue to what being governed by olfaction is like. He can’t eat many if not most things, though people around him chew and dunk and slurp on obliviously. He loves spinach, for example, but only a particular rarified type. His gift affords him a good life as a private investigator, sometimes lending his service to police. But the toll is significant; it interferes with his connection to women who eventually can’t abide him turning up his nose at so many things they want and savor, including so much of what they might have ordered for dinner.

The woman who detests him most fiercely is played with implacable hostility by Mariya Anikanova. Remember the android in Alien who so admired the uncompromising hostility the alien species directed toward humans? That android would find much to admire in Yulia, whose splendid portrayal of diamond-hard anger is one reason to watch the series.

In effect the Sniffer sees through his nose; the aromas it brings to him are translated into smoky visual images. His is a case of synesthesia run amok.

We’ve all watched some, maybe too much, of English television. Lately Israeli TV attracts due attention. The Sniffer is one reason among others to scout out the pleasures of Russian TV.

— Harvey Blume

Thanks for the mixed bag of reviews; enjoyed them all. If one phrase might suffice to sum up the zeitgeist, I’m going with Allen Michie’s “this weird David Lynch movie we’re living in right now.”