Opera Album Review: Donizetti’s Teacher Takes Center Stage — Mayr’s “I Cherusci”

By Ralph P Locke

This splendid world-premiere recording proves that, as a composer of opera, Johann Simon Mayr had “the whole package.”

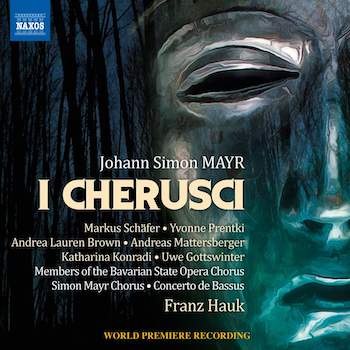

MAYR: I Cherusci

Yvonne Prentki (Tusnelda), Andrea Lauren Brown (Tamaro), Katharina Konradi (Ercilda), Markus Schäfer (Treuta), Uwe Gottswinter (Carilo), Andreas Mattersberger (Zarasto).

Concerto de Bassus, Simon Mayr Chorus and Bavarian State Opera Chorus Members/ Franz Hauk

Naxos 8.660399-400 [2 CDs] 153 minutes

Click here to purchase or to hear the beginning of each track.

Johann Simon (Giovanni Simone) Mayr (1763-1845) was arguably the most important composer of opera and sacred music in Italy during the 1790s-1820s. He is thus a kind of missing link between the Cimarosa/Mozart/Salieri era and the triumphant reign (in Italy and also abroad) of Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, and early Verdi. Mayr was born and received his early training in (German-speaking) Bavaria before moving to Italy for further training. He eventually made Bergamo his primary center of activity, but also composed for theaters up and down the peninsula. Donizetti became his pupil, and learned much from this skillful master.

Johann Simon (Giovanni Simone) Mayr (1763-1845) was arguably the most important composer of opera and sacred music in Italy during the 1790s-1820s. He is thus a kind of missing link between the Cimarosa/Mozart/Salieri era and the triumphant reign (in Italy and also abroad) of Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, and early Verdi. Mayr was born and received his early training in (German-speaking) Bavaria before moving to Italy for further training. He eventually made Bergamo his primary center of activity, but also composed for theaters up and down the peninsula. Donizetti became his pupil, and learned much from this skillful master.

Dozens of Mayr’s works have been revived on CD in recent years, thanks largely to scholar-conductor Franz Hauk. His recordings have been generally praised by music critics (including myself). Hauk prefers to keep his orchestral forces small, and uses period instruments, sometimes reducing the string orchestra to a chamber group in accompanied recitatives or even in some passages within an aria. He also keeps the tempo moving, without much broadening toward a cadence. The results therefore often sound gentle and cozy, rather than grand and rhetorical. By contrast, a 2015 recording of Mayr’s most-recorded opera, Medea in Corinto, from the Valle d’Itria Festival, uses a full modern-instrument orchestra and singers with big, sometimes edgy voices, under the renowned maestro Fabio Luisi, who does not hesitate to push ahead or pull back. (See my review. Medea, when first performed, featured three of the most renowned singers of the age: Isabella Colbran and two tenors: Andrea Nozzari and Manuel García. Modern recordings have been graced by singers as mellifluous as Bruce Ford, Raúl Vargas, and Alek Shrader and as magnetic as Marisa Galvany and Nadja Michael.)

That opera, Medea, is marvelous but atypical. Though it was first performed in 1813, Mayr repeatedly reworked it thereafter. The final version that we tend to hear today thus bears many similarities to what Rossini and Donizetti were doing during the latter part of Mayr’s career. To get a sense of “Classic-era” Mayr, one can listen (with pleasure!) to Hauk’s fine recording of the 1797 opera Telemaco nell’isola di Calipso, starring two singers who are also on the present recording: Andrea Lauren Brown as the enchantress Calypso and Markus Schäfer as Telemachus (son of the famous Odysseus). (I reviewed that as well.)

The present recording is the world premiere of I Cherusci (The Cheruscans, 1808). It allows us to hear a Mayr opera that, stylistically, sits about halfway between the poised, gracious Telemaco and the marvelously propulsive Medea. The text, by the prolific Gaetano Rossi (future librettist of Rossini’s Semiramide), tells of struggles between tribes in ancient Germania around the time of Christ. The characters include Treuta, king of the Marcomanni (a tribe located in or near what would later be called Bohemia), various Cheruscans (whom, in the opera, the Marcomanni have recently defeated), and the Cheruscan princess Tusnelda (who has been taken captive by the victorious Marcomanni).

Composer Johann Simon Mayr. Photo: Wiki Commons.

The booklet essay argues that the plot is a commentary on political events of the day (Napoleon’s conquering of the German-speaking lands) but also stresses that the opera focuses primarily on “the father-daughter constellation” in ways that anticipate major Verdi operas.

The plot hinges on Tamaro, a Cheruscan warrior (pants role), who tries to free Tusnelda. His actions stir the wrath of Treuta, who has developed a secret affection for the captive maiden. Local/period color is provided by the unpleasant figure Zarasto, a druid priest who is trying to bring back the practice of human sacrifice. Will Tusnelda and Tamaro be his chosen victims? No, because a secret treasure chest contains a necklace proving that…(etc.).

OK, so there are unlikely moments in the plot. But no more than in, say, Il trovatore. More to the point is that the arias and ensembles are neatly constructed, and the melodic lines are shapely and often peppy. The energy is softened a bit by the “early music” style of singing and by the limited size (and gut strings) of the period-instrument orchestra, but there is also an advantage: the listener never feels pummeled.

As always with Mayr, the music is nicely varied in tempo and manner, and the individual numbers, including several two-tempo arias, never outstay their welcome. Expansion is welcome when it comes: a nine-minute number integrates effectively a minor-mode choral march (indicating the setting-up of the intended sacrifice) with, in accompanied recitative, shifting reactions for the seemingly doomed Tusnelda. Some numbers are graced with notable passages for solo instruments, for example, violin, double-bass, flute, clarinet, horn or — years before Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor — harp. The stopped notes of the unnamed hornist in Ercilda’s Act 1 aria are clearly audible yet well integrated into the musical line. A plus for the listener: no secco recitative! Mayr “musicalizes” everything, as Rossini would eventually do in his later serious operas.

I particularly admired tenor Markus Schäfer in the role of the deeply torn King Treuta; now in his late 50s, the tenor preserves much of his long-admired histrionic skill, vocal beauty, and (in coloratura) flexibility. Soprano Andrea Lauren Brown (from Delaware) sounds fuller than I recall from some earlier recordings. She conveys Tamaro’s principled heroism well, and her florid passages are fleet if somewhat undemonstrative (quite unlike the attention-getting rat-a-tat precision to which Joan Sutherland and Marilyn Horne once accustomed us). The other standout in the cast is the light soprano Katharina Konradi (Kirghiz-born, now living in Germany). I could listen to her all day. Yvonne Prentki is bright-toned and very skillful in coloratura but a little edgy at times.

This painting by Friedrich Gunkel (1862–1864) of a battle between the Cheruscans (under Arminius) against the Romans (under Varus), in the latter years of the ninth century A.D. (The painting was destroyed in World War II.).

What an astounding era the early 19th century was for Italian opera! And how marvelous that we now have ready access to works such as this, in sympathetic and secure performances! If you, like more and more opera lovers these days, hold Mozart’s Idomeneo and Clemenza in warm affection, you will be delighted to get to know Mayr’s Cherusci.

But I must end with a gripe: there is no libretto! And the synopsis is too brief and lacks track numbers. Naxos usually handles such things more helpfully. It doesn’t help that characters sometimes refer to another character, or even to themselves, in the third person, so you can easily get confused who is singing about whom. (I never could get a clear sense of which of the three tenors in secondary roles was which, whereas the three sopranos have helpfully different-sounding voices).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.