Opera Album Review: Before “Carmen,” There Was Massenet’s Spanish-Tinged “Don César de Bazan”

By Ralph P Locke

World premiere recording of an utterly delicious 1872 comic opera, recorded without spoken dialogue, so you can just revel in the music and the singing.

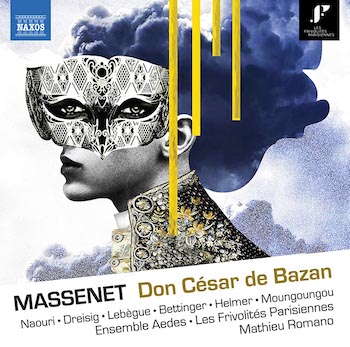

MASSENET: Don César de Bazan, second version (1888)

Elsa Dreisig (Maritana), Marion Lebègue (Lazarille), Thomas Bettinger (King Charles II of Spain), Laurent Naouri (Don César de Bazan), Christian Helmer (king’s minister), Christian Moungoungou (captain of the guard).

Ensemble Aedes, Orchestre des Frivolités Parisiennes, cond. Mathieu Romano.

Naxos 8.660464-65 [2 CDs] 112 minutes. Click here to purchase or to listen to the beginning of each track.

Over the past fifty years, opera lovers have been rediscovering the works of Jules Massenet. Manon never completely vanished from the repertory, and Thaïs held on a bit. But it took the devotion of many conductors and opera-house administrators to unearth and reinstate such forgotten works as Cendrillon (recently revived at the Met for mezzo Joyce DiDonato) and Don Quichotte (which Sarah Caldwell’s Opera Company of Boston brought back in 1974, in a boldly imaginative production featuring mezzo Mignon Dunn as Dulcinée).

Over the past fifty years, opera lovers have been rediscovering the works of Jules Massenet. Manon never completely vanished from the repertory, and Thaïs held on a bit. But it took the devotion of many conductors and opera-house administrators to unearth and reinstate such forgotten works as Cendrillon (recently revived at the Met for mezzo Joyce DiDonato) and Don Quichotte (which Sarah Caldwell’s Opera Company of Boston brought back in 1974, in a boldly imaginative production featuring mezzo Mignon Dunn as Dulcinée).

All of those are pieces with largely or completely continuous music, though Manon does have spoken dialogue, often occurring over orchestral music.

A bigger challenge comes with the present work, Don César de Bazan (1872). Like other French comic operas of the era (by Auber, Adam, Offenbach, and so on), the work often include lengthy stretches of spoken dialogue, without a peep from the orchestra, that are crucial for understanding the story and for motivating—setting up in a meaningful way—each subsequent musical number.

This is not so strange in the theater: we are, after all, accustomed to a similar basic set-up from Gilbert and Sullivan and from Broadway musicals. Still, such works present a challenge: do you try to train a group of international singers to deliver rapid banter rapid banter in French? And how can they make it fully heard in today’s mammoth opera houses?

As for record collectors—and, even more, people who stream their classical music—most of them (I suspect) want to hear music, not entire minutes of unbroken spoken exchanges. For such folks, I now have a recommendation: this world-premiere recording of an earlyish and utterly delicious Massenet opéra-comique, Don César de Bazan (1872, rev. 1888), with all the musical numbers but only the tiniest fragments of the original and extensive spoken dialogue.

The libretto derives from a French stage comedy that incorporated some characters from Victor Hugo’s drama Ruy Blas (1838) and that quickly became the basis for an important English-language opera, Vincent Wallace’s Maritana (1845). (If the name Ruy Blas is familiar, it’s because Mendelssohn, in 1839, wrote an overture inspired by the Hugo play.)

Briefly: the Spanish king, Charles II, becomes infatuated with the street-singer Maritana, who, being a Gypsy (today we might say a Romany or member of the Rom people), is considered too low-born to become his mistress.

The manipulative royal minister Don José de Santarém, wishing to please the king any way he can, arranges for Maritana to marry Don César shortly before the latter is executed. This would make her a countess and, an hour later, a widow.

(Here, as often in the opéra-comique genre, grim matters are pushed into the ridiculous. Furthermore, Don César’s crime is that he fought a duel during . . . Holy Week! Presumably this detail expresses a typically French critique of Spanish Catholicism for being legalistic and hypocritical. Writers associated with the French Enlightenment had urged, more consistently and without invoking the sanctity of the church calendar, that dueling be outlawed outright.)

The minister persuades César to go through with the plan, but there is a pleasant surprise: the apprentice-soldier Lazarille removes the bullets from the muskets before they are fired at César. (Sidelight: I suspect that Lazarille was named after the “anti-hero” of Lazarillo de Tormes, a renowned early Spanish novel from 1554.)

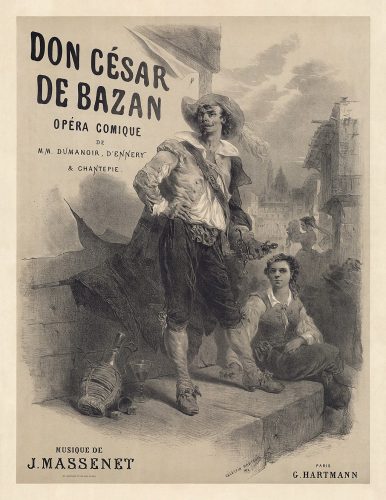

The title page of the score for Don César de Bazan.

Back to the plot: The king tries to woo Maritana, but is astounded to see the supposedly dead César enter. This is perhaps the most comical and theatrically effective moment in the whole work. After some further revelations (César kills the duplicitous José offstage), the king recognizes, with that magnanimity common to many stage monarchs, that he has no right to insist on Maritana’s love. He blesses the union of the two lovers and names César governor of Granada. The orphan boy Lazarille agrees to go off with the happy couple who have been so kind to him. All hail the happy outcome and the generosity of the king.

On the spectrum of French comic opera, Massenet’s Don César falls somewhat toward the bouffe side, represented most famously by dozens of Offenbach works. It contains numerous short strophic songs (in French: couplets): that is, numbers that give out a single tune several times in a row, to different words (often with a refrain line or lines).

The sense of fleetness carries over into the longer numbers, such as the three act-finales, which move quickly from one kind of music to the next. The ninth “number” of Act 2 consists of a series of sub-numbers: a drinking song, a march-like song about the delights of pillaging an enemy town, a passage in which the town judge reads Don César’s arrest warrant, a gorgeous orchestral passage beneath some spoken dialogue, and a reflective “madrigal” for Don César about his imminent death. The public reading of the warrant takes place between the second and third strophes of the “pillaging” song, helping to put the dreary news in an ironic context, as if suggesting (rightly) that things will work out for our baritone (anti-)hero somehow.

As is typical of comic opera almost everywhere, the music is frequently animated by dance rhythms. Not surprisingly for a composer who had already completed the first two of his seven colorful orchestral suites for orchestra (including the “Hungarian,” no. 2), the orchestral writing is an exquisite tissue of colors. Lazarille’s sad song in Act 1, for example, features lovely contributions from the English horn.

The work is studded with Spanish rhythms and excerpts from actual Spanish tunes, such as the famous “Jota aragonesa” (in Don César’s first aria). These remind us that Bizet’s Carmen (1875: three years later) was not the only French opera of its era to include a good deal of Spanish “local color.” A third roughly contemporary work to do the same thing is Offenbach’s Maître Péronilla (1878; see my review of its world-premiere recording).

In 1888, Massenet orchestrated the work afresh, because the score and parts had been destroyed in a theater fire. He took the opportunity to make substantial revisions. The recording presents the opera in a version as complete as possible, giving us the 1888 version plus several short numbers from the 1872 original version that were orchestrated specifically for this recording. (We are not told who took care of this, but the job seems well done.)

The performances are delightful. The singers—who have mostly young, firm voices—toss off the elegant and tuneful vocal lines with a casual ease that reflects their familiarity with the medium and manner of French comic opera. Particularly amusing is the duet for two baritones, Don José and Don César in Act 2, played by, respectively, the veteran Laurent Naouri (much loved at the Met) and the young Christian Helmer, the latter at one point amusingly imitating the voice of an elder “duenna.” Naouri, at age 55, has developed a mild wobble, but his voice is otherwise still beautiful and his experience on stage helps him gain our sympathy and hold it.

The soprano Elsa Dreisig, as the Gypsy street-singer Maritana, is a real find. I would love to hear her sing other roles, serious as well as comic. Marion Lebègue is utterly reliable, and touchingly sad, as the teenage boy Lazarille. (Oh, the French, with their love of trouser roles!)

The singers largely pronounce their Rs in the colloquial French way, at the back of the throat, rather than with an Italianate trill at the tip of the tongue. This helps make the work feel conversational and persuasive—or as persuasive as it tries to be, which is not very. There are so many artifices in the plot—as in many stage works of, again, Offenbach—that one is hard put to take the characters seriously. But there are many pleasurable moments along the way. And, the work is economical: 21 numbers (or more if one counts the separate internal sections) in three acts, and all in less than two hours.

Soprano Elsa Dreisig — a real find.

The recorded sound is excellent, with superb balance between voices and small orchestra. (This was done under studio conditions, not during a performance.) Everything is clearly audible, except for some slightly underbalanced soft chords in the strings, a problem I’ve noticed in many opera recordings.

I will henceforth be on the lookout for other recordings by this orchestra, choral group, and conductor, all previously unknown to me.

The work contains occasional passages of mélodrame (spoken dialogue over orchestral music); here some of these are rendered as orchestral music alone, without the spoken dialogue. For practical reasons, presumably, a passage specified for organ is given out, instead, by a mini-choir of solo string instruments.

The excellent booklet essay and synopsis/analysis by Robert Ignatius Letellier are marred only by some unidiomatic word choices that may confuse: in English, one doesn’t say that couplets (strophic songs—see above) are a “sub-genre” of opéra-comique but a frequent “component” or “standard option” within it. And there is no “Captain of Arquebusiers” in the plot (as if Arquebusiers were the name of a town). He is the captain of the arquebusiers (the musketeers).

My only other complaint is more fundamental, and one that I have with many current opera releases: the libretto is only available online and, worse, with no translation. It does, though, include all the spoken dialogue that has been omitted from the recording. So, if your French is good, you can create a full performance in your head, hitting the pause button as needed.

In short, this recording is a constant delight. It will be especially welcomed by people who love French light opera yet don’t want to have to sit through lengthy spoken interchanges or keep hitting “skip forward” on the remote control. Grab it now, as who knows how long it will last in the catalogue. There is unlikely to be a second recording anytime soon.

And, if you have any influence on your local opera company or college opera studio, by all means encourage them to try this amazing work. If somebody penned a lively English translation, the resulting show—to use Broadway language—could be a real “wow” and “have legs.”

UPDATE: Speaking of forgotten nineteenth-century operas, two CDs that I reviewed recently are among the winners of the 2021 International Classical Music Awards. The jury every year consists of critics from major music magazines on the European Continent (including lands as far east as Russia and Turkey; yes, the portion of Turkey that lies west of the Bosporus has long been considered part of Europe). The two recordings that I so loved were Anima Rara, a collection of Italian (verismo) and French arias sung by Ermonela Jaho, and the first recording of a nearly forgotten opera by Saint-Saëns: Le timbre d’argent. (I’ll post my review of the latter here soon.)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Don César de Bazan, Elsa Dreisig, Jules Massenet, MASSENET, Marion Lebègue