Country Music CD Review: “We Shall All Be Reunited: The Bristol Sessions, 1927 & 1928” — Revising Musical History

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

Producer Ted Olson is on a mission in We Shall Be Reunited to do justice to the past; he imagines a beautiful alternative to the current ballyhooed origin story of country music.

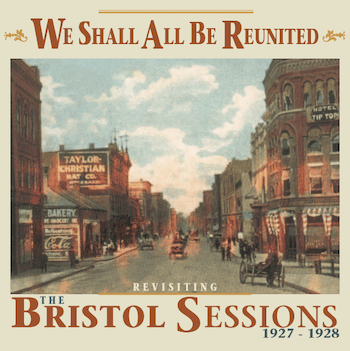

Historic view of Bristol’s State Street, with Virginia to the right and Tennessee to the left. Note the Taylor-Christian Hat Co. building (408 State Street), the site of the 1927 Bristol Sessions.

Between 1923 and 1931 Northern record companies made “remote” or “location” recordings of vernacular music in the US South, white and Black. They are sometimes referred to as “field recordings,” though folklorists would disagree. These were not haphazard, serendipitous, or casual sessions. And they were not made for the sake of documentation. It was all about profit.

Since the turn of the century, a number of record labels — Columbia, Edison, and Victor among them — had wanted to tap into the urban immigrant markets in the North via “foreign” records. Beginning with World War I, these so-called foreign records were increasingly sourced from within US immigrant communities. It was a modestly profitable move. One large group of potential customers, perceived to be closer to home (geographically and culturally), was in the South. Since the days of blackface minstrelsy, Northern record companies had gone about both misrepresenting and commercializing Southern art and culture. These recordings were labeled “hillbilly” records for white markets and “race” records for Black markets and exported around the world. (Of course, the longtime cross-pollination of styles among musicians of both races in the South was not acknowledged.)

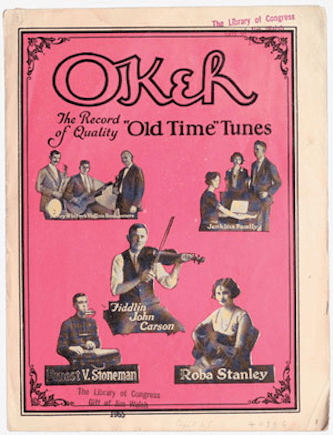

The companies hedged their bets in these endeavors in the hinterland, fearing they could not pull off a marriage between Southern vernacular music and “location recording.” In 1923, “remote” recordings were made for OKeh records, under the direction of Ralph Peer in Atlanta, St. Louis, Detroit, Chicago, and New Orleans. By 1927 OKeh would add Dallas, St. Petersburg, FL, Cleveland, Buffalo, Kansas City, Annapolis, Asheville, NC, and Cincinnati. Historian Tony Russell has written that “between the summer of 1923 and the summer of 1927, the five major record companies, Victor, Columbia, OKeh, Brunswick and Gennett, conducted forty-four recording trips, visiting thirteen cities in eleven states: from Atlanta, New Orleans, and Dallas to St. Louis, Salt Lake City, and Buffalo.” In these sessions the companies came into town with a healthy dose of skepticism: along with the high tech equipment there was usually at least one sure-fire hitmaker on the schedule to be recorded.

By the summer of 1927 the favorite sites for the big labels — somewhere between 40 and 50% of the total — were Southern cities that had established strong sales and distribution connections. When Columbia joined OKeh in the location recording game in 1925, they chose Atlanta and New Orleans; the label would return to both for the next two years. When Brunswick joined the trend in 1926, they picked St. Louis. The quality of the music was not particularly crucial: what was important was feeding the region’s existing markets. In fact, a local distributor would often find himself having to put on the hat of a talent scout with little warning.

Enter the fabled “Bristol Sessions,” glorified as the ground zero of the modern country music industry. In the summer of 1927, Ralph Peer, on the heels of his work pioneering location recordings with OKeh, went at the behest of Victor to Bristol, a town that straddled the Tennessee/Virginia line. Virginian Ernest V. Stoneman was expected to record in the session; he was a proven hitmaker who had already scored commercial success with a 1926 tune for OKeh in New York — “The Sinking of the Titanic.” Peer announced his session in a newspaper advertisement for a Clark-Jones-Sheeley Co. in this way: “The Victor Co. will have a recording machine in Bristol for 10 days beginning Monday to record records — Inquire at our store.” Historian Ed Ward has noted that the paper’s reporters also alerted locals to Stoneman’s success, pointing out he was earning three-and-a-half times an average annual salary for his recordings. Peer brought his state-of-the-art recording equipment into the second and third floors of the Taylor-Christian Hat Company building on the Tennessee side of Bristol’s State Street. There, from July 25 to August 5, 1927, Peer and his engineers produced 76 recordings. The sessions were so successful that Peer would return in 1928. They would result in a variety of “hillbilly” and “race” records for the label, ranging from fiddle tunes to sacred songs, from blues to string bands. Among those responding to the ad were the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, whose successful careers would fuel the myth of the Bristol sessions.

Enter the fabled “Bristol Sessions,” glorified as the ground zero of the modern country music industry. In the summer of 1927, Ralph Peer, on the heels of his work pioneering location recordings with OKeh, went at the behest of Victor to Bristol, a town that straddled the Tennessee/Virginia line. Virginian Ernest V. Stoneman was expected to record in the session; he was a proven hitmaker who had already scored commercial success with a 1926 tune for OKeh in New York — “The Sinking of the Titanic.” Peer announced his session in a newspaper advertisement for a Clark-Jones-Sheeley Co. in this way: “The Victor Co. will have a recording machine in Bristol for 10 days beginning Monday to record records — Inquire at our store.” Historian Ed Ward has noted that the paper’s reporters also alerted locals to Stoneman’s success, pointing out he was earning three-and-a-half times an average annual salary for his recordings. Peer brought his state-of-the-art recording equipment into the second and third floors of the Taylor-Christian Hat Company building on the Tennessee side of Bristol’s State Street. There, from July 25 to August 5, 1927, Peer and his engineers produced 76 recordings. The sessions were so successful that Peer would return in 1928. They would result in a variety of “hillbilly” and “race” records for the label, ranging from fiddle tunes to sacred songs, from blues to string bands. Among those responding to the ad were the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, whose successful careers would fuel the myth of the Bristol sessions.

Ted Olson has been fighting a reductionist fantasy of the Bristol Sessions and their significance for some time. A professor in Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University, he’s behind the recent Bear Family release We Shall All Be Reunited: The Bristol Sessions, 1927 & 1928. This isn’t the first time Olson and the Bear Family, an indie German record label, have collaborated. He was behind Bear Family’s 2011 box set The Bristol Sessions – The Big Bang of Country Music. Ironically, Olson has made it his mission to deny that the Bristol Sessions were the “Big Bang of Country Music.” The decision to brand them as “transcendent” took a powerful step forward in the early ’70s, reinforced by the 1971 unveiling of a granite monument in Bristol that honored Rodgers and the Carters to the exclusion of anyone else. (Overseeing the ceremony was Carter family son-in-law Johnny Cash, who had just wrapped up his TV show for Columbia Pictures, and Ralph Peer II, heir to Ralph Peer’s legacy and eventual CEO of Peermusic.) The monument proclaims country music’s birth date: “August 2, 1927.” Olson responds to this notion in his notes for We Shall All Be Reunited: “The identification of…a ‘birthdate’ for nationally relevant country music — if one accepts that the genre was born in Bristol at all — is puzzling, as the original Carter Family trio made four recordings in Bristol on August 1, 1927. On August 2 Sara and Maybelle made two recordings as a duo (A.P. left to fix a flat tire for the car they had driven to Bristol), while Rodgers first recorded on August 4.” It also ignores Peer’s second Bristol sessions in 1928.

If the monument erectors couldn’t get their dates right, they at least put a simplifying message across. Cash called the Bristol Sessions “the single most important event in the history of country music.” In 1986 a mural painted in Bristol depicted Peer, the Carters, Rodgers, and Ernest and Hattie Stoneman… a nod to a predecessor who had been overlooked. In 1987 the Country Music Foundation released a collection of recordings culled from the 1927 sessions. Olson argues that, while this effort “offered a detailed portrayal of what had happened in Bristol during 1927, the album had the effect of marginalizing the 1928 Bristol sessions, which remained in the shadows.” The urge to simplify continued to undercut a complex understanding of the Bristol Sessions. The Virginia General Assembly officially recognized Bristol as “the Birthplace of Country Music” in 1995, and the US Congress did likewise in 1998.

Olson is on a quest to evaluate the Bristol Sessions accurately: he wants a modulated, not overblown, appreciation of their significance. As late as 2019, Ken Burns’s Country Music series on PBS perpetuated the birth date fiction. “Viewed by many millions,” writes Olson, “Country Music, ignoring counter-narratives accounting for other early influences upon country music, uncritically co-opted the 1927 Bristol myth as the central event in the genre’s creation story.” Nine years later the fight continues. Olson has worked with the Bear Family to release a complete Bristol Sessions box set. So we can all make our own conclusions about what went on.

Olson has worked with Bear Family on albums featuring other smaller-town location recordings. He and the label have collaborated on box sets of the 1928-29 (2013) session in Johnson City and Knoxville in 1929-30 (2016). So what are Olson and Bear Family on about? They want to undercut a flawed country music narrative that elevates the Carter Family and Rodgers to the exclusion of others. There were other powerful musicians at that time in Bristol. We Shall All Be Reunited: The Bristol Sessions, 1927 & 1928 features 15 tracks from 1927, but also 11 from 1928. This gives us an opportunity to hear talents that had found earlier recognition, such as Ernest V. Stoneman and Henry Whitter. And we are exposed to Peer’s lesser “discoveries,” such as Blind Alfred Reed, the Black blues harpist El Watson, and Tarter & Gay, a Black duo from the same county as the Carters. There is also the strong (if faltering) voice of the minister and songwriter Alfred G. Karnes. The work of these artists is placed alongside tracks by Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family. Olson argues that, because famous tracks are put back in context, we are given a more accurate look at the sessions: “Peer and Victor likely did not anticipate the popularity of the Carter Family’s music, as that debut was the label’s twelfth release of recordings from Bristol.” Rodgers’s Bristol recordings did not catch on with the public, but they spurred an interest from Victor to record him in New Jersey.

What makes Olson’s curation valuable is that it sheds new light on the Bristol Sessions simply by beginning with Stoneman’s “Sweeping Through the Gates” and ending with Karnes’s “We Shall All Be Reunited.” This box set is not another tired exercise in celebrating musical legends that the recording companies found lucrative to market. It explores all the music and its players, so listeners can hear how sacred music could be turned to profit while continuing to encapsulate the lived experiences of the cultures who turned to it for sustenance. We Shall All Be Reunited is a bit of a paradox: it reunites the disparate musical traditions that were captured in Bristol — it is not a selection of “greatest hits.” This expanded view gives us an intimation of what went unrecorded, the communal voices that inspired the music.

In that sense, Olson is on a mission to do justice to the past. And he is pretty much on his own. “Who will mobilize a truth-telling demythologizing education effort?,” he asks in the album’s notes. “By all evidence, not politicians, tourism officials, or the mainstream media. When waxing nostalgic about the 1927 Bristol sessions, those folks have revealed an unwavering obeisance to a vernacular origin myth that is entrenched yet unsustainable in the face of recent scholarship.” What Olson imagines is a beautiful alternative to the current ballyhooed origin story. For him, Bristol, Johnson City, and Knoxville are all on the same continuum. And they are intimately connected to Atlanta, New Orleans, and St. Louis, along with Detroit and Buffalo. The musicians who created “country music” include Stoneman, Fiddlin’ John Carson (recorded in Atlanta in 1923) and Blind Willie Johnson (recorded in Dallas in 1927). These voices cry out to be reunited.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: 1927 & 1928, coutnry music, Ted Olson, the Bristol Session

Nice historical background to country music. My mother’s folks came from Bristol, VA before settling in southeast Oklahoma. Lots of good music from there too.