Book Review: “The Ocean House” — Infiltrating the Beachheads of Memory

By David Daniel

Mary-Beth Hughes’s penetrating glimpses into the depths of her characters’ lives make us more deeply aware of our own.

The Ocean House by Mary-Beth Hughes. Atlantic Monthly Press, 243 pages, $26.

Buy at Bookshop

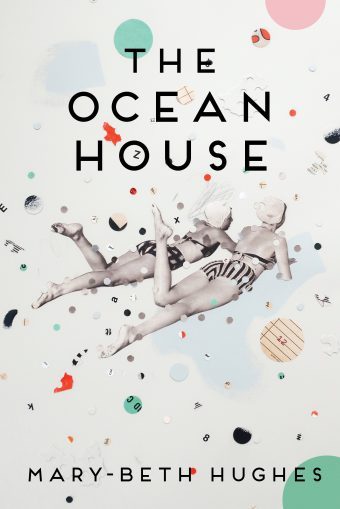

The cover art of Mary-Beth Hughes’s new collection of short fiction might give one to expect a breezy beach read full of nostalgia, sisterhood, and sangria, but The Ocean House is something quite powerfully different. Most of the 11 stories here do name-check their coastal setting — the city of Long Branch on the Jersey Shore — but that feels almost incidental because their true terrain is the interior of the strange and wounded individuals who congregate at the beach.

Hughes’s deep dive into its characters is reminiscent of Virginia Woolf’s close study of her Bloomsbury denizens, or J.D. Salinger’s psychological probings of the Glass family. Regarding her resources of art and craft, Hughes is just as masterful. She gives us recurring characters, like Faith, her aging mother Irene, Faith’s daughter Cece, an ex-husband, friends Sebastian and Chloe — perhaps a dozen people in all play a role in these linked tales.

In addition to the collection’s protagonists, whose story arcs continually intersect, there are other, more peripheral players — like Courtney Ruddy, who takes center stage in the first story, the title yarn. Thereafter Ruddy haunts the interstices of other lives in myriad ways: a former friend who was by turns kind, manipulative, and enigmatic. And there’s the blurry Hadley: brother, brother-in-law, uncle, scamp, dupe — depending on a particular character’s perspective.

Hughes doles out details deftly; nothing is incidental. A bus driver “shimmied a pink rolling duffel out of the stow space onto the sidewalk and slammed shut the hold.” An emotion hits a character with the abruptness of “a dropped utensil.” A mother has an epiphany when she looks carefully at her college freshman daughter: the girl “turned away now so Faith could fully view the unimaginative snake tattoo crawling in blurry green ink up her neck into the bristles of new growth on her shaved scalp…”

In medias res is Hughes’s go-to opening narrative gambit. A sampling of first lines: “Connor was still in his crib, an elaborate crib, something with slide bolts between the slats and a mattress made of material astronauts might sleep on” (“The Healing Zone”). “Of all the tasks her new sister-in-law, Ell, had assigned, the eggshells were the most difficult” (“The Elixir”). “In the middle was the horror of her sister’s death” (“How the Poets Learned to Love Her”). And, worthy of F. Scott Fitzgerald: “When Lee-Ann first arrived in Long Branch by bus, she hovered on the raised step looking all around her for a signal from someone, the driver, anyone, to go ahead and make her way over to the quaint green canopy the chamber of commerce erected in the summer months” (“Outcast”). The tales live up to these beckoning beginnings by slowly revealing who the characters are and why their lives should matter to the reader

Hughes is an honest but modulated storyteller who has no interest in Jersey Shore stereotypes. Along with the familial angst served up by contemporary fiction, there are moments of tenderness that resist sentimentality and cliché. All of the people here are hemmed in, throttled by class, family, and unrealistic expectations. Some of the best of the tales involve Cece, whom we first meet as a small child and later see as a college freshman. Eventually, we encounter a young woman struggling to negotiate her way through a world she neither understands nor is ever likely to be understood by. All of the characters come off as passive, acted upon rather than acting: Hughes’s females often seen tranquilized, her males tend to be feckless husbands and fathers.

Author Mary-Beth Hughes — she is interested in inner terrain, the landscape of memory and repressed emotions.

Hughes’s storytelling strategy can be angular and demanding; she often asks readers to make connections based on very oblique evidence. For those willing to play psychological detective, the rewards are bountiful. Most of the 11 stories are well worth the effort. “Here You Are” and “Summerspace” (both involving Cece), and “Dove” are masterful. The title story, the first, and longest, in the collection, requires and rewards close attention. Only a couple of the stories don’t measure up. “The Elixir” is a misfire; this is an overwrought yarn auditioning for an MFA thesis. “California,” the final story, is also somewhat fuzzy. The Ocean House‘s most unsettling story, “The Pitch” (it opens with “When we heard what happened to you, we thought, Wow, that’s it” and intensifies disturbingly from there), is a one-sided riff spoken to an unnamed “you,” whose identity isn’t made clear until several stories later. The offhand voice of the narrator heightens the story’s sense of menace.

And speaking of dialogue, Hughes’s sense of the “right thing to say” is dead on. Even though she presents speech without quotation marks (a technique that has become vogue, and often feels like affectation — even when Cormac McCarthy does it), she pulls it off.

To vary that old truism about politics, all stories are local. Hughes isn’t writing about the touristy seaside playground hyped in four-color brochures, a glamorous setting for summer reads. Long Branch (by literary happenstance, the real-life hometown of Dorothy Parker, Norman Mailer, and Robert Pinsky) was once upon a time a bustling beach resort, with gated swim clubs, leafy enclaves, and a relaxed social whirl. That past represents a kind of lost Eden for which Hughes’s adults feel a confused nostalgia. Their children only want to escape a dour reality.

Aside from an allusion to the city’s once-prominent beach clubs, a diner, and certain avenues, the locale could be almost anywhere. There is no whiff of salt air or squawk of seagulls wheeling overhead, no snap of driftwood bonfires. Hughes’s fictional world taps into the inner terrain of her characters, their landscapes of memory and repressed emotions. The Ocean House is a collection so varied in its telling, rich in its details, and character-divining that it demands to be reread — and not simply to keep its portraits of lost souls straight (though there is that). Her penetrating glimpses into the depths of these lives make us more deeply aware of our own.

David Daniel is the author of more than a dozen books, including four entries in the prize-winning Alex Rasmussen mystery series. His most recent book is Inflections & Innuendos, a collection of flash fiction. He blogs regularly @Richardhowe.com.

Now I’ll have to buy the book.

Thanks.

Enjoyable review. Good writing.

The stories would have to be good to be as pleasurable as the review.

[…] Source link […]