Film Review: “Sound of Metal” — A Test of Character

By Tim Jackson

To Sound of Metal’s credit, the narrative remains open-ended, refusing to descend into a predictable “Hollywood” story of triumph over adversity.

Sound of Metal, directed by Darius Marder. Screening at the Kendall Square Cinema. Streaming on Amazon Prime on December 4.

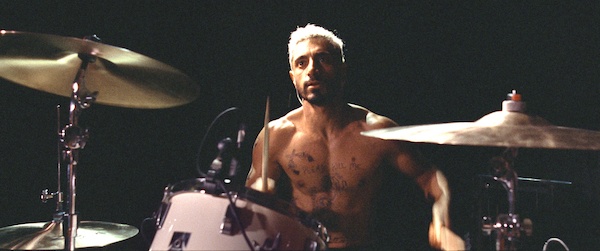

Riz Ahmed in a scene from Sound of Metal. Photo: Amazon Studios.

Darius Marder’s Sound of Metal begins with an industrial metal duo in performance (shot live at the Middle East Club in Cambridge). The guitarist, Lou (Olivia Cooke), emits distorted guitar sounds matched by a vocal that is more primal scream than singing. The scars on her arm suggest that she has had a past of self-harm. Ruben (Riz Ahmed), a reformed heroin addict, is lean, bare-chested, and covered in tattoos. He fidgets restlessly at the drums. His chest reads “Please Kill Me,” which is the title of a classic book on punk rock history. On cue, he launches into an assault on the kit, arms flailing, double bass drum pedals thundering out 16th notes at warp speed

The film then abruptly cuts to silence. It is the following morning. The couple are in their Airstream trailer home where Ruben blends green smoothies, makes breakfast and coffee, exercises, and cleans their portable recording console. Without warning, sounds around him become muffled, voices are indistinct. He realizes that he is losing his hearing.

As a drummer myself, the fear of hearing loss is real. It can result from the persistent volume of electric instruments, along with the high-end pitch of metal cymbals and the compression of thousands of hits on a snare drum so close to the ears night after night, particularly when they are unprotected. Ruben’s diagnosis, however, is Sudden Deafness Syndrome, which is not exclusively the result of “performance” trauma. Causes for the condition can include drug use, infection, diabetes, even genetics. This broadside, coming in the middle of a tour, is life changing. Ruben initially responds by undergoing stages of grief: anger followed by denial. An audiologist (local actor, Tom Kemp) tells him that the only way to recover his hearing would be through cochlear implants. Hope of surgery keeps his dreams of a music career alive. Understandably depressed, he agrees to rehabilitation and temporary residency at a rural deaf community. There he finds a group of similarly recovering addicts along with a school for deaf children. The resulting journey of loss and acceptance will test his resolve. One could call it a story of sound and mettle: a test of character.

Marder’s screenplay (c0-written with Derek Cianfrance) never turns into clichéd feel-good conflict. The second act takes place at the residency. Ruben sits with the community’s leader (Paul Rici), who is as calm as a Zen master. Rici, an experienced actor, is a CODA, or Child of Deaf Adults. Grounded in authenticity, his straightforward performance is powerfully effective. Displaying how to lip read, use ASL, and communicate through a computer monitor, the leader sets out the responsibilities and challenges ahead. Beneath this discussion lies the need for his charges to make a crucial acknowledgement — that they are nonhearing. “Stillness,” he explains, “that’s the kingdom of God. We’re looking for a solution to this” pointing to his head and, pointing to his ears, “Not this.” With the same commitment that he made to his music career, Ruben applies himself to learning American Sign Language and becoming a mentor to the students.

The film’s carefully constructed audio design alternates between silence and the minutiae of what’s audible. Sometimes the audio is distorted or removed completely. This agile dramatization of hearing is worth experiencing in a theater or on headphones. The shock of Ruben’s trauma is eased somewhat when he sees that people who are deaf are a motley bunch, a community of unique and scrappy individuals. Life without sound may be as much a gift as a handicap. Their teacher (the marvelous deaf actress Lauren Ridloff) is beautiful and patient and brings Ruben a greater appreciation of the deaf world. Still, he can never quite give up the uncertain hope that, if he can raise the funds for cochlear surgery, he will triumph over this misfortune and revive his career.

To Sound of Metal‘s credit, the narrative remains open-ended, refusing to descend into a predictable “Hollywood” story of triumph over adversity. No spoilers from me about how Ruben’s and Lou’s past histories deepen our understanding of them both. Both Ahmad and Cooke give strong performances: in real life she is an accomplished singer and he, after less than a year of coaching (with help of carefully edited footage), is a serviceable drummer and a powerfully committed actor. The elemental core of this story is about the strength it takes to take command of the present, recognizing, appreciating, and normalizing difference — it is a celebration of the journey, not the destination.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.