Opera Review: Paisiello’s “Le gare generose” — Italians, Quakers, and Slavery in 18th-century Boston

By Ralph P. Locke

The lively world-premiere recording of Giovanni Paisiello’s Le gare generose proves why the composer was in demand all across Europe.

Giovanni Paisiello, Le gare generose (3-act comic opera, 1786).

Marianna Mappa (Gelinda), Maria Luisa Casali (Miss Nab), Giulia Mattiello (Miss Meri), Manuel Amati (Don Berlicco), Stefano Marchisio (Mister Dull), Bruno Taddia (Bastiano).

Giovanni Paisiello Festival Orchestra, cond. Giovanni di Stefano.

Bongiovanni 2575/76 (2 CDs) 131 minutes.

Click to purchase.

Lots of operas involve major characters who would have been considered exotic at the time. Some even take place entirely in an exotic land. For a North American reader (or indeed a New Englander!), Paisiello’s Le gare generose (Naples, 1786) is unusually intriguing because the exotic location is late-18th-century Boston (with a reference at one point to Halifax), as seen by various Italians: three of the characters plus, of course, the composer and his librettist, Giuseppe Palomba. It was an enormous hit at the time, reportedly receiving 37 different stagings by the year 1800.

Lots of operas involve major characters who would have been considered exotic at the time. Some even take place entirely in an exotic land. For a North American reader (or indeed a New Englander!), Paisiello’s Le gare generose (Naples, 1786) is unusually intriguing because the exotic location is late-18th-century Boston (with a reference at one point to Halifax), as seen by various Italians: three of the characters plus, of course, the composer and his librettist, Giuseppe Palomba. It was an enormous hit at the time, reportedly receiving 37 different stagings by the year 1800.

The untranslatable title of Paisiello’s opera refers to characters who, at the end of the opera, try to outdo each other in generosity. Generosity and an indifference to fashion and social rank were characteristics that people on the European Continent in the late 18th century often attributed to Quakers. Notably to those who had settled in North America. Palomba based his libretto freely on an earlier one by Raniero Calzabigi in which the main male character and his niece were Quakers. The equivalent characters in Paisiello’s opera are not explicitly referred to as Quakers, but many of their personalities, views, and behaviors remain.

Mister Dull (baritone) is effectively the lord of the manor. His last name mocks his Quakerish insistence on avoiding egotism and displays of wealth. His 40-year-old unmarried niece, Miss Meri (spelled this way so that it will be pronounced “Mary”) insists on choosing a husband for herself. She attributes this strength of will to her Scottish ancestry, but Italians thought of it as a notable feature of Quaker women, whether in Britain or in North America. (Readers interested in now-little-known 18th-century operatic stereotypes of Americans will want to look at Pierpaolo Polzonetti’s wide-ranging book Italian Opera in the Age of the American Revolution.)

The less-principled values of Old Europe are represented here by Don Berlicco, an Italian businessman who is a seducer, untrustworthy in love. As the action evolves, he also shows himself to be nasty and punitive. Dull’s daughter Miss Nab is mean-spirited in her own way. She openly challenges her father’s egalitarian pronouncements; she revels in having been “born to command” the slaves in the household. These include an African whom we never see, but we learn that he is chained in the basement. Dull, perhaps revealing his own lack of prejudice (about his slaves!), recognizes that the man is “astute” and at one point thinks of asking him to report anything he overhears.

The other two major characters — Gelinda and Bastiano (their real names, but they are using pseudonyms in Boston) — are a youngish Italian couple, not yet married. They were captured at sea by pirates and then purchased by Mister Dull. This has made them house-slaves to the Dull (but hardly dull!) family, a situation that creates palpable tension with Mister Dull’s professed values.

Gelinda and Bastiano resemble the Susanna-Figaro pairing in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, which was first performed the same year (but in Vienna, far distant from Naples). Gelinda is as strategic as Susanna and sharper-tongued. Bastiano, rather like Figaro, is jealous when Mister Dull becomes obsessed with Gelinda (to the latter’s annoyance). Bastiano’s entire part is written in Neapolitan dialect (the work was first performed in Naples) and includes numerous comical images and asides, such as references to sausages, castanets, and a donkey.

I found Paisiello’s music cogent and always apt to situation and character. There are some 13 arias, each lasting a mere two to four minutes and divided into several short movements (for example, Berlicco’s Act 1 aria). There are also four duets, two trios, a quintet, and of course an extended finale to each of the two acts (respectively, 19 and 18 minutes). You can hear the beginning of each track here. The entire recording is available on various streaming services, uninterrupted, or, free, at YouTube (but broken into tracks separated by ads).

A passage at the end of the Act 1 quartet shows Paisiello’s musicodramatic skill: the four characters state a single melodic phrase one after the other, as if to show how intricately they are all entwined in a situation that cannot possibly be resolved to everybody’s satisfaction. (The four characters here are Dull, Miss Meri, and the Italian slave-couple; Meri has taken a shine to Bastiano, though her passion is as doomed as Dull’s infatuation with Gelinda.)

I particularly enjoyed several ensemble scenes and act-finales, which become a whirlwind of interactivity between and among the characters.

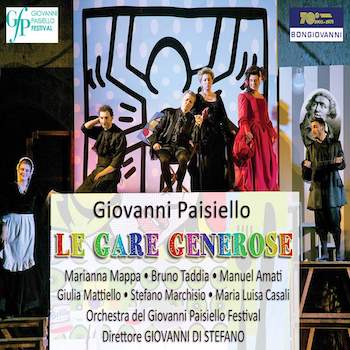

A scene from the stage production heard in the Bongiovanni recording of Le gare generose under review. Photo: Presto Music.

There is no indication whether cuts have been made, but the version used is certainly effective. The Festival claims that the production was the first modern revival of a version from Naples in 1800 (which perhaps included changes in Gelinda’s aria –the unclear essay seems to suggest this).

I find no evidence that the work has ever been recorded before, in any version. So it’s a relief to report that the singers are all adequate for the purpose, though the only two I’d make an effort to hear in other repertory are the bright soprano Marianna Mappa (the Gelinda) and the light tenor Manuel Amati (the borderline-evil Berlicco). The so-called bass who sings Bastiano has almost no voice in his lowest register. And the vibrato-deprived tones of the “contralto” (I’d say mezzo) who sings Miss Meri make it glaringly obvious at times that her pitch on certain notes is . . . approximate. The audience seems small but confirms my own preference by showing particular appreciation for the Gelinda.

All cast members understand what they’re singing to each other. The non-bass handles Bastiano’s regional accent and vocabulary well. But he is hardly as skillful and varied as the equivalent comic “Neapolitan” performers in operas I’ve reviewed by Bellini and Nicola De Giosa.

The small chamber orchestra plays scrappily but with spirit, and the harpsichordist keeps recitatives moving smartly along. The solo violin, oboe, and bassoon sympathize touchingly with Gelinda in her arietta within the Act 1 finale (not easily found because it is not given its own track number). Certain “joins” between tracks are clumsily edited.

Photos on the front panel suggest that the production was low-budget but roughly appropriate to the era. One “updated” element: a big backdrop showed a drawing — by modern-day graphic artist Keith Haring — of an archetypal human figure (outlined, with no face) trying to escape from a box. Some of the characters in this opera have indeed been, and continue to be, “boxed in” by some of the others. And having an American-style image in the background was probably thought appropriate, even though the century is wrong.

A scene from the stage production heard in the Bongiovanni recording of Le gare generose under review. Photo: Presto Music.

In short, Le gare generose provides a trenchant portrayal of the society of Paisiello’s day, though framed as an evening’s entertainment. The spoonful of sugar in no way dilutes the medicine. I hope some college opera studio or regional opera company will look into this and other Paisiello comic operas. Audiences would love such works, though they might, at times, wince, for the best of reasons.

The original libretto is available online (at the Library of Congress and other sites). But Bongiovanni’s booklet, which contains the libretto and a good English translation, seems only to be available to purchasers of the CD set. I don’t find it downloadable anywhere, even at the Naxos Music Library site, though the recording itself can be streamed there.

For anybody interested in what Paisiello offers in the operatic realm, I strongly recommend, first, La grotta di Trofonio (vividly performed in a 2017 release; here’s a video excerpt), which makes its own intriguing comments on humanity, power, and delusion. Then Le gare generose. And finally, less fun but featuring an amazing Rosa Bove as the military general Oraspe, the opera seria Zenobia in Palmira (likewise brought to us by the admirably risk-taking firm Bongiovanni). There’s an immense number of intriguing and gratifying operas out there that we never get to see and hear!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.