Book Review: A Brilliant “Homeland Elegies” — Indispensable Witness

By Roberta Silman

What Ayad Akhtar reveals, with stunning detail and a passion and an urgency rarely seen in American fiction, is that his is a story marked by a loneliness similar to that found in Melville, Dreiser, and T.S. Eliot, among others, and that puts him squarely in their company.

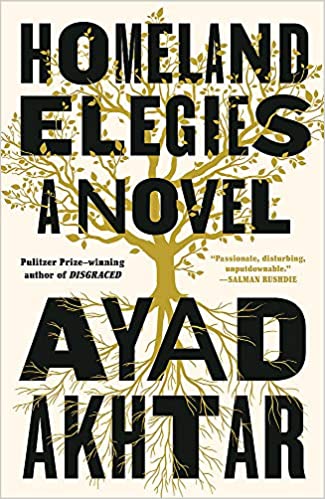

Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar. Little Brown, 345 pages, $28.

Buy at Bookshop

That loneliness is part of the human condition is accepted by most people, but Samantha Rose Hill, in an interesting piece in The Browser, confirms that its hold on us has grown with the rise of extremism and autocracy. For example, Hill writes,

The ideological apparatus of Trump’s machinery is succeeding in part because even we who wish to oppose him are losing sight of our ability to tell the difference between what is real and what is imagination run amok. That is, we are losing the ability to discern our own thoughts, to engage in a critical conversation with ourselves. And this is the real marker of totalitarianism. We become isolated from one another, and in our aloneness we allow our imagination to create tales of fear that turn us further away from one another, from our ability to discern what is a real threat and what is being conjured. What is a figment of the imagination and what is reflective of reality? We forget in some ways that our culture is marked by alienation, competitiveness, and loneliness. And if we allow ourselves to succumb to the darker side of our imagination, then we are playing into the hands of those who wish to quell our ability to resist.

In addition to Trump and his despicable cronies, we also have COVID-19 and the belated acknowledgment of the systemic racism that has tainted our democracy from its very beginnings. So now we are not only confronting our own guilt and shame, but we are also better able to understand what people of color have been experiencing for a long time. And we can, hopefully, comprehend — from our isolation during the pandemic and our anxieties about the state of our democracy — the profound loneliness that has been part of their lives for far too long. A loneliness that is more concomitant with the ideas of Hannah Arendt, whose work Hill has studied closely:

as a kind of wilderness where a person feels deserted by all worldliness and human companionship, even when surrounded by others. The word she used in her mother tongue for loneliness was Verlassenheit – a state of being abandoned, or abandon-ness. Loneliness, she argued, is ‘among the most radical and desperate experiences of man,’ because in loneliness we are unable to realise our full capacity for action as human beings. When we experience loneliness, we lose the ability to experience anything else; and, in loneliness, we are unable to make new beginnings.

When I read that last paragraph I wished that my husband Robert Silman was still alive and we could continue our long conversation about Arendt, who was a writer he and his students read with unflagging interest in his signature course, The Philosophy of Technology. And I found Arendt’s words resonating in a new way for me because I had also just begun reading the superb new novel Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar.

It is a remarkable book, billed as a novel because what the narrator, also named Ayad Akhtar, relates may or may not be true. My suspicion is that there is a kernel of truth in most of the stories (the volume is a series of interconnected stories, essays, memoirs). Indeed, the epigraph from the book is from the graphic writer Alison Bechdel: “I can only make things up about things that have already happened . . .” It doesn’t really matter if every word is true. What matters is that this Ayad is determined to make us understand what it means to be a first generation Muslim-American in a country that many of us have idealized, to our peril. What Ayad reveals, with stunning detail and a passion and an urgency rarely seen in American fiction, is that his is a story marked by a loneliness similar to that found in Melville, Dreiser, and T.S. Eliot, among others, and that puts him squarely in their company.

Akhtar was born in Staten Island in 1972 to Pakistani physician parents and brought up in Wisconsin. You might know his name because he is the author of Disgraced, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2012, and was recently the subject of a long profile in The New Yorker. He is now President of PEN, the writers’ organization to which I have belonged for more than 40 years. But more important than his ambition and subsequent fame at such a young age is his willingness to lay himself bare. Although his work could fall into the category called auto-fiction which I usually find unbelievably boring (think Knausgaard and Ben Lerner and Martin Amis at his worst), this is prose that sweeps you along, whether you want to go or not, and embraces the reader in a story that’s so compelling you feel you are a participant. His subject is, like his idol Whitman, America itself. And how our ideas of who we are shape who we are, often in ways both subtle and destructive. Yet how those very ideas and ideals keep us going in a world that is increasingly complicated and often bleak.

The book begins and ends with a professor he calls Mary Moroni, who taught him how to think critically and encouraged him to honor his dreams and his talent. Who, despite her own struggles — she is gay and smarter than most of her peers in academia — is a source of real support for Ayad from the time he meets her as a freshman in college until he comes as a distinguished guest to talk to her class. She is an anchor for him, as only a beloved teacher can be, as he searches not only for truth but how best to tell it. Although not a writer herself, she seems to have a seventh sense about what he needs; one of the most touching moments in this book is when she writes him a long letter after the disaster of 9/11.

The other anchor in the book, far more present and far more troublesome, is his father Sikander, a famous heart doctor who has treated Donald Trump, who votes for him in 2016, who drinks too much, has a gambling addiction, fathered an illegitimate daughter — Ayad’s half sister — with a woman who was one of Trump’s favorite prostitutes, and whose chase for the American dream ends with him so bankrupt emotionally and financially that he spends his last years back in Pakistan, the country he fled in the 1960s. But it is in the scenes with his father, those beautifully wrought exchanges in which all the love and conflict are exposed between this father and his beta — that term of affection so much richer than just the English word son — that the book soars. It is as if Ayad has absorbed all of Roth and Bellow, two of his favorite writers, and taken them to another level.

In addition to Mary and Sikander who, literally, bookend this novel, there’s a large cast of characters — relatives, friends, strangers, acquaintances, theater folk, lovers, a sleazy financial “wizard” who brings Ayad the economic security he so badly needs, and even Muhammad, who is as crucial to the Muslim worldview as Jesus and Moses and Buddha are to the belief systems of others. So we get, along the way, an understanding of the Muslim customs and values that are crucial to so many of the people in this novel, and how some of them who came to America with high hopes could never adjust to life here.

One of those is Ayad’s mother Fatima, whose presence in the novel is crucial. (It was only on the second reading that I connected so poignantly with her.) This is a woman who married the wrong man, who suffered unspeakable childhood traumas associated with the Partition of the Subcontinent, who lost her first son Imtiaz, who was convinced she brought illness upon herself, and whose honesty and loneliness are among what drives Ayad to bear witness. Here he is at her bedside when she is dying:

For all the literary speculation about her secret summations brought me to see how little I really knew her and confronted me with the deepest resentment of my life—that despite the daily demonstrations of love, the doting, the sacrifices, the unceasing maternal care, I never truly felt loved by her. I’d never felt loved because I’d never known who was loving me and never felt certain she knew whom or what she was loving. . . . I never felt she saw me; or, rather, never felt certain the person looking out at me was really and truly her and was really and truly looking out at me. I saw now that the source of my life’s work—reading, literature, theater—was in part the pursuit of something as simple as my mother’s gaze, a gaze she gave happily to books.

What Ayad wants is familiar to all of us. But what children don’t understand is that their parents had lives before they were born, and that their parents’ youth and early adulthood formed the basis of their inner lives. In plain language, there are barriers to knowledge that prevail in every generation — it is one of the abiding mysteries of life — and it is exactly because of those unknowable parts of our lives that great plays and novels and stories are written.

It is noteworthy that in one of their last exchanges, when Ayad assures his mom that he is happy here because he can be a writer, she confesses,

“I never really liked it here.”

“I know, Mom.”

“You do?” She seemed both surprised and pleased to hear it.

I nodded. Then her expression changed again abruptly, narrow with a troubled thought.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Don’t be mad.”

“About what?”

“You’re one of them now. Write about them. Don’t write about us.”

“But I don’t choose my subjects, Mom. They choose me.”

“You can change that.”

But here Fatima is wrong. And Ayad’s stubborn reply is proof of Akhtar’s value in our present literary landscape. He has no choice but to examine all the aspects of his life as a Muslim American, a project he started with his first novel American Dervish, continued with Disgraced and Junk, and which I suspect he will work at as long as he lives. He loves those he writes about too much to consign them to oblivion. Although Fatima might have protested in her usual modest way that she and Sikander were just ordinary folk, there is no such thing as “ordinary folk” to a writer like Ayad Akhtar. And there is nothing ordinary about what happened to those who left after Partition or were displaced from the Middle East in the last half of the 20th century and the first two decades of the 21st. Or what has happened to America since 9/11, and how that event has affected every Muslim person living here.

Author Ayad Akhtar

So Homeland Elegies is exactly what its title suggests: a brilliant look at America right now, and far more than a history lesson or a picaresque journey. Thus, it minces no words about how our capitalist system has corrupted all of us — perhaps beyond any hope of redemption — and how money often ruins lives; how sex and power have too much leverage; how we are now, finally, beginning to face the music. It takes great courage to write a novel of such breadth, a novel which, in its meticulous accounting of so many aspects of American life, gives us a picture of our country as moving and as devastating as Roth’s American Pastoral. Even its form signals something new and exciting. Although it may strike some readers as a baggy monster because of its ability to move the narrative into so many places, it is anything but. The precision and the beauty of the prose are exemplary, every word counts and every path explored gives this novel not only a clear trajectory, but also an intimacy that only first-class fiction possesses. This is a novel that takes real risks, risks that just add to its power to connect to its readers.

How I wish that Fatima had lived to read this book. For here is a gritty, penetrating look at our country from a badly needed perspective. A look at our flawed, money-grubbing country, whose inequities have gone ignored for too long. A book that delves deep because its narrator cannot sit by and watch the place he considers home go to the dogs. A book that refuses to fall for the clichés of smugness and celebration that cloud our vision. A book that can ease the loneliness we have all been living with and that can encourage us to the “new beginnings” we have been so unable to foresee for far too long.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

A magnetic assessment.

I agree with the reviewer that this book shares insights, both terrible and true, into America. The author’s Muslim heritage gives him a particular lens, but what he sees is the country where all of us live. His insights will ring true for just about everyone.