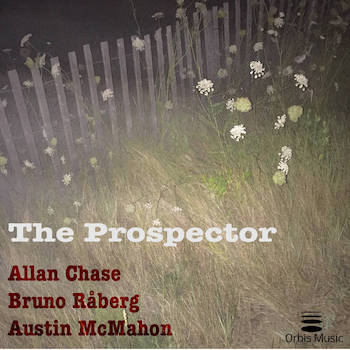

Jazz Album Review: “The Prospector” — A Saxophone-Bass-Drums Combination to Treasure

By Steve Elman

Nothing detracts from the essentials here – three fine players in creative conversation.

The Prospector, by Bruno Råberg (Orbis Music, 2020; also hearable via bandcamp.com)

A new jazz recording invites the ear of the listener into a world of its own, a world not even the musicians who created it can share. Everything about a first listen is sonically fresh, existing as a whole entity rather than in the various elements the musicians selected to put it together. So that first encounter ought not to be a casual one; art music deserves your full informed attention.

This is one reason I wanted to stuff my ears with music made by other saxophone-bass-drums combinations before sitting down to dig into The Prospector, bassist Bruno Råberg’s new CD (Orbis Music, 2020). I wanted to familiarize myself with the other sound-worlds from this galaxy before touching down on Råberg’s.

If you’d like to do the same — or if this post makes you curious about the history of the saxophone trio — I’ve prepared a companion post to this one that will show you just how much variety there is.

What I learned from this experience (and now from multiple listens to The Prospector) is that Råberg has chosen his elements wisely — a saxophonist (Allan Chase) with whom he has long experience and easy rapport, a drummer (Austin McMahon) with a firm hand and good ears, varied repertoire that shows off each player to advantage, balance in the spotlight so that no one actor dominates the stage, and sonic decorations that change the acoustic so your ear is often surprised and pleased.

You may think that the sax-bass-drums combination isn’t common. You would be wrong. It took me many hours of listening even to make a judicious selection of the available recordings, and I’m convinced there are many more I didn’t even consider. Many of the masters have tried their hands at it — Sonny Rollins, Lee Konitz, John Coltrane, Joe Henderson, Ornette Coleman, Sam Rivers, Steve Lacy — and their trio recordings are almost always among the ones that critics consider their best.

Most of the other dates I can point to are led by the saxophonist (natch), and as a result, many of them are very sax-heavy. There are even outings like David Murray’s 3D Family and Jon Irabagon’s Foxy that test the listener’s endurance with the saxophone’s dominance.

On the other end of the continuum, there are sax-bass-drums trios that by their very names and natures are intended to be leaderless and mutually cooperative. The best ones — Air, The Fringe, Open Sky, Fly — live up to that promise in very distinctive ways.

In between, there are other leaders — again, mostly saxophonists — who treat their partners as honored guests and make sure that the “supporting players” are real contributors — Jason Stein’s recordings with his group Locksmith Isidore, Branford Marsalis’s Trio Jeepy and Joe Lovano’s Sounds of Joy are great examples.

Råberg’s The Prospector is one of these latter, and my research around it surprised me with a minor revelation. Based on what I’ve found to date, I believe that it is only the second full-length jazz recording led by a bassist whose partners are just one saxophonist and just one drummer. The only other bassist who has offered something in the same format is Henry Grimes, and his Us Free: Fish Stories, from 2014, is a different kettle of . . . no, I won’t say it.

Råberg is a bass virtuoso, a sophisticated composer, a seasoned veteran of jazz and other musics, and a respected teacher who has chosen to make his home in our town. He has an enormous sound, and as both leader and engineer for this recording, he has made sure that sound is reproduced with impeccable fidelity — almost as if your ear is inside his instrument.

l to r: Allan Chase, Austin McMahon, and Bruno Råberg. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

My regard for his partners is great. I consider saxophonist Allan Chase a friend, and I have been honored to hear him many times and in many contexts. He simply never disappoints; when you go to hear him play, you can be confident that he will be unfailingly creative and amazingly consistent — as he is here. His solos, like those of Lee Konitz, make good use of space and show that he is really thinking as he plays. On the other hand, he can play streams of arpeggios whip-fast when they are appropriate. Austin McMahon, the youngest of the three artists on The Prospector, rises to the challenge of working with two people who are greatly admired by their peers, and he never sounds awed by their presence.

Råberg has decided that the simple combination of saxophone, bass, and drums is a bit too austere for a full CD, and he has decorated the proceedings in a number of ways, usually by giving Chase more to do by overdubbing. The most elaborately transformed track is “Dissipating Clouds,” where Chase doubles Råberg’s bass line on baritone saxophone throughout and plays three saxophone parts (two on soprano and one on alto) in the theme statements. Chase also solos on both soprano and alto here, and provides backup figures on two of his axes behind both solos. On other tunes, there are some judicious uses of studio effects — some echoey extensions in the theme of “Isometric Rotation” and the impression of Chase playing soprano sax off in the distance behind his alto and soprano on “Demos & Phobos.”

However, nothing detracts from the essentials here — three fine players in creative conversation. The material, all original, is strong, ranging from formal compositions, mostly by Råberg, to completely free improv. The title tune and lead track comes from Chase, and, once a rocky rhythm is set up, his alto and soprano saxes present an Ornettish line in three sections. The first and second lines of this theme are the same long phrase, played in unison, except for harmony on the last note. The third line is another long phrase with a contrasting tonal center, where the saxes play in harmony. The band takes an open approach on this, at first in tempo, then slipping farther and farther away until they are playing semi-free. At exactly the right moment, Råberg brings the bass line down to earth, and the head returns, with a snappy last note.

Råberg wrote most of the tunes here, and I found “Isometric Rotation” particularly attractive. It has qualities in common with Monk’s tunes — it seems abstract at first, becomes clearer as it goes along, and returns at the end like an old friend. It also has a lovely solo by Chase on baritone sax, who shows off a great throaty sound that evokes Harry Carney and Hamiet Bluiett at the same time.

Råberg’s “Rockside Haiku” is cleverly structured, moving in two directions at once in the improv. It’s “undecorated” — just the three players as they might be heard in a live situation. McMahon sets things up with mallets (I confess that I love this sound, which creates an immediate sense of tension). Then there is a theme statement with Chase’s soprano saxophone and Råberg’s arco bass, which has a nice way of etching that theme into the listener’s ear. Both show off some glissandi at the midpoint of the theme, with Chase using embouchure tricks to mimic what comes naturally to the bass. Chase then solos over a sort of rubato foundation, unpacking his beautiful singing tone. The support slips into tempo, with McMahon using his brushes, but the bassist and the saxophonist begin to ease away from the root notes as their conversation develops.

McMahon’s “Lockleigh,” with a folky Scottish-highlands feel, is a standout. Chase’s alto is doing the singing here, and his slow vibrato, judiciously used, adds to the vocal quality. My only cavil with this fine performance is the drummer’s over-reliance on his snare. It seems to me that a little more “color percussion” would have suited the melody better than a steady slow beat, which really isn’t needed, since Råberg handles that role rock-solidly throughout.

McMahon is heard to better effect on Råberg’s “Triloka,” where his solo, with the bassist providing an ostinato foundation, defines space nicely. A relatively tight acoustic predominates when he concentrates on his traps, with tambourine for a little extra decoration, and then the sky seems to open up when he moves to his cymbals.

“Duo Rotation II” is at the other end of the continuum. There is no prearrangement, but the performance has a gratifying arc. Chase begins on alto, with quick lines over just the drums. Soon the bass joins in, establishing a fast-free tempo. Chase quickly drops out, leaving Råberg and McMahon to converse for a while. Chase comes back in, and McMahon drops out. Råberg switches over to his bow, and his lovely long tones begin to predominate, with Chase following him into a more meditative space. Both reach into their highest registers, but very softly. McMahon responds by providing delicately bowed cymbals and tiny splashes. Chase comes back to his middle register with some long notes that are almost like bowed bass. Some taps from the drummer punctuate the final seconds, and all subside to a quiet finish.

Each of the performances here shows an equal measure of careful preparation and spontaneous inspiration — plenty to enjoy on the first listening, and plenty more to savor when you return for rehearings, as I’m sure you will.

More:

Råberg plays in another intimate context in an online stream October 30 with the venerable saxophonist Stan Strickland, as part of the Boiler House Jazz Series at the Charles River Museum. To see it, follow this link.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

[…] A new jazz recording invites the ear of the listener into a world of its own, a world not even the musicians who created it can share. Everything about a first listen is sonically fresh, existing as a whole entity rather than in the various elements the musicians selected to put it together. So that first… Jazz Album Review: “The Prospector” – A Saxophone-Bass-Drums Combination to Treasure – The … […]

[…] A new jazz recording invites the ear of the listener into a world of its own, a world not even the musicians who created it can share. Everything about a first listen is sonically fresh, existing as a whole entity rather than in the various elements the musicians selected to put it together. So that first… Jazz Album Review: “The Prospector” – A Saxophone-Bass-Drums Combination to Treasure – The … […]

[…] A new jazz recording invites the ear of the listener into a world of its own, a world not even the musicians who created it can share. Everything about a first listen is sonically fresh, existing as a whole entity rather than in the various elements the musicians selected to put it together. So that first… Jazz Album Review: “The Prospector” – A Saxophone-Bass-Drums Combination to Treasure – The … […]

[…] A new jazz recording invites the ear of the listener into a world of its own, a world not even the musicians who created it can share. Everything about a first listen is sonically fresh, existing as a whole entity rather than in the various elements the musicians selected to put it together. So that first… Jazz Album Review: “The Prospector” – A Saxophone-Bass-Drums Combination to Treasure – The … […]