Film Review: “White Riot” — The Superb, Sadly Relevant, Story of Rock Against Racism

By Betsy Sherman

Director Rubika Shah ends her film on a high note, but no one watching could conclude that the struggle is over

White Riot, directed by Rubika Shah. Available through the Brattle Theatre’s Virtual Screening Room.

Fans at some show put on by Rock Against Racism — from White Riot.

“Our job was to peel back the Union Jack and reveal the swastika.”

The words are spoken by Red Saunders in the superb, and sadly relevant-to-our-time, White Riot, which documents the grassroots group he co-founded, Rock Against Racism (RAR). He’s speaking about a racist, anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, white-supremacist group that wrapped itself in the flag — Britain’s National Front party (NF) in the mid-’70s.

RAR pursued the goal of derailing the NF’s terror campaign against non-white communities by staging concerts in which Black reggae bands and white punk bands would play on the same bill to multiracial audiences. At that time, it was a radical notion that took a lot of faith, and physical courage, to pull off. With music as an entryway, the group was able to make crystal clear the agenda that the self-styled patriotic party was trying to carry out.

White Riot has music by bands including X-Ray Spex (fronted by the biracial Poly Styrene), 999, Steel Pulse, Gang of Four, Matumbi, Misty in Roots, Sham 69 and the Clash. The left-leaning Clash did the song that gives the documentary its name; while it has a reactionary-sounding title, when you actually listen to the lyrics you see they call for a white rebellion in league with a Black one. It’s an instance of going beyond the surface into the meat of the thing — exactly what RAR advocated, and did so well.

The movie provides some background about what led up to the bleak ’70s in the UK, when the nation needed help from the International Monetary Fund and unemployment was high. A certain element searched for a scapegoat, and found it in the immigrants from former colonies (in South Asia and the Caribbean) who had arrived in Britain after the war to meet industry’s need for cheap labor. Conservative Member of Parliament Enoch Powell fanned the flames of racism with a slogan “Keep Britain White,” and the fascist National Front became emboldened, marching through immigrant neighborhoods and telling people to go back where they came from (even the British-born children). They enlisted ready-to-rumble skinheads as their shock force.

To the RAR founders interviewed in the film, who were already protesting NF bigotry, a flashpoint was when Eric Clapton — whose music was based on that of Black blues artists — went on a keep-Britain-white rant at a concert, saying the immigrants should be sent back, except using much uglier terms than “immigrant.” Saunders (a photographer who had an agitprop theater group, Kartoon Klowns), typesetter Roger Huddle, and others wrote letters to the editors of the English music press denouncing Clapton and inviting people to help launch a group called Rock Against Racism. Other early organizers interviewed in the film are graphic artist Ruth Gregory, RAR office manager Kate Webb, and Barbados-born musician/record producer Dennis Bovell.

The film shows some of those original handwritten replies, many by teenagers. These young people would go on to found local chapters that presented multiracial shows. London’s RAR shared its wisdom, sending out guidelines on how to deal with venues and how to “defend” your p.a. system from attack.

And attacks there were, at the gigs and on the street during RAR marches. Supportive kids were cautioned to take off their RAR badges before they walked out of the venue, so they wouldn’t be targets. Pervez Bilgrami, of the majority-South Asian band Alien Kulture, recalls how dozens of hostile skins would be waiting to jump them outside the stage door.

The original RAR office was fire-bombed; at their new place, they’d have to pile sand underneath the mail slot, in case thugs used it to pour in gasoline. Law enforcers were clearly on the side of the white supremacists. “The police didn’t help us, they hindered us,” says Saunders.

In Huddle’s words, the RAR fanzine Temporary Hoarding was part of the group’s “hands-on guerilla activities.” Its cut-and-paste punk aesthetic spotlit the voices of little-known musicians while it asked tough questions of better-known ones. Articles delved into issues like the notorious “sus” laws (analogous to stop-and-frisk, in which police disproportionately hassled people of color) and the war in Northern Ireland. Lucy Toothpaste wrote about gay, lesbian, and feminist issues; she and other RAR women formed a sibling group, Rock Against Sexism.

The film has a wealth of archival footage, from racist politicians seeming to rattle otherwise unflappable interviewers by suggesting how they would racially cleanse the nation, to ethnic slurs used as punch lines in sitcoms of the time, to on-the-street interviews with kids, some of them gung-ho NF, but others intent on pushing back against the bigots, learning from leaflets produced by RAR and their allies, the Anti-Nazi League.

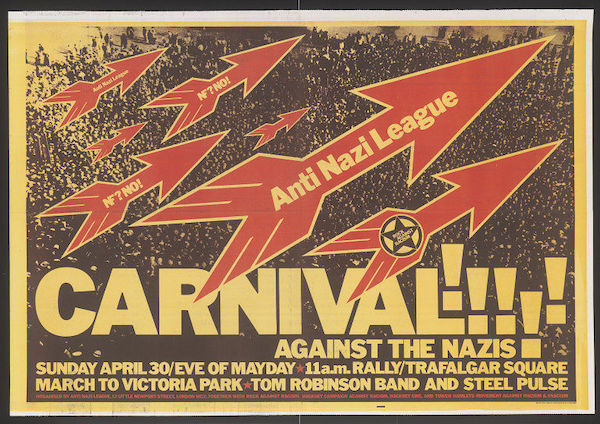

Of those early days in ’76 and ’77 Saunders says, “It was a scary moment, ’cause punk could’ve gone either way.” A figure who illustrates that crossroads — taking antiestablishment energy toward either inclusiveness or exclusion — is singer Jimmy Pursey. His hard-charging punk band, Sham 69, didn’t catch on in the US but had a big following in the UK, especially among disaffected working-class youth, a percentage of which were right-wing skinheads. Looking back, the RAR-ers give Sham 69 credit for taking the risk of doing a gig with a Black reggae band, but, as we see in concert footage, the show generates tremendous tension and fights break out. The concert in shambles, Pursey says backstage, “I preach peace.… I do me best.” He’ll make a stronger statement to his fan base in the gig that the movie builds up to, the April 30, 1978, Carnival Against the Nazis.

This outdoor show, envisioned as a musical march across a swath of London, from Trafalgar Square to a section of NF-supporting territory in East London, was a gamble. No one knew how many RAR supporters would show up, or if they would outnumber the inevitable NF counter-marchers. As it happened, 80,000 fans came from all over the nation, not only for the great lineup (including Steel Pulse, the Clash, and the Tom Robinson Band) but also, as archival interviews show, to affirm that the UK could be a place that welcomed many cultures. Whatever NF-ers had planned to disrupt the day retreated into the woodwork.

Director Rubika Shah ends her film on this high note, but no one watching could conclude that the struggle is over. She shoots the core group of interviewees with admiration: they’re pillars, but also human beings. The movie’s visuals are brisk, featuring animation that makes use of the dynamic Temporary Hoarding graphics. One minor drawback is the unidentified insertion of footage from the 1980 feature film Rude Boy, a look at the Clash through the eyes of a roadie. It’s a bit jarring when suddenly a clip of Clash members will be much better lit than surrounding archival footage (and have a choreographed feel). Identifying the clips would have helped.

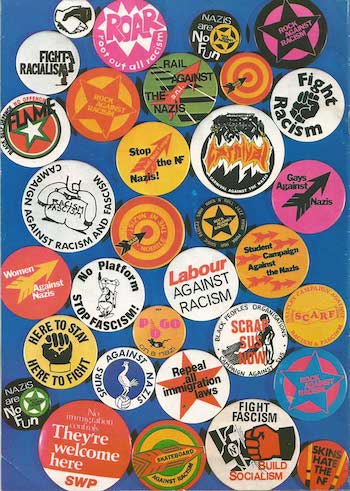

In the early ’80s I used to import punk badges from the UK and sell them in the Boston area. I ordered RAR merchandise from the London office. Now I get to see the people who were on the other side of that correspondence, which is very cool. I don’t remember whether I knew at the time that they used the one-syllable “rahr” rather than the three-syllable “r-a-r.” In context, it seems a sign of the urgency of the task at hand. It’s an urgency as important now as it was then.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

All the power in the hands of the people rich enough to buy it . Those lyrics are just as relevant today . If not more . Black,White unite and take these people on . We’ve got the numbers!!