Opera Album Review: A Baroque Opera — Ripped from 18th Century Headlines

By Ralph P. Locke

Telemann’s music here is a delight, often resembling, in style, appeal, and high craftmanship, what we find in Handel’s operas and oratorios.

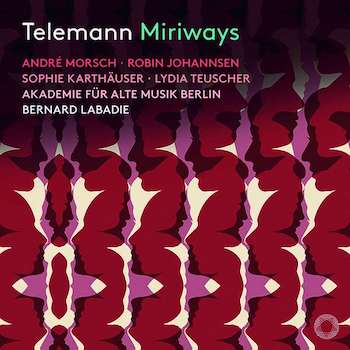

Georg Philipp Telemann, Miriways (opera)

Sophie Karthäuser (Bemira), Robin Johannsen (Prince Sophi), Lydia Teuscher (Nisibis), Marie-Claude Chappuis (Samischa), Michael Nagy (Murzah), André Morsch (Miriways).

Academie für Alte Musik Berlin, conducted by Bernard Labadie.

Pentatone 5186842 [2 CDs] 155 minutes.

Click here to purchase.

Are old operas relevant to the concerns of the modern age? The question has been agitating musicians, stage directors, audiences, and critics for decades. One response has been to create updated and creatively “interventionist” productions of works from the standard repertory — presentations that often try to “shake the dust” off of a work, to reveal the beating heart that speaks to us today.

Are old operas relevant to the concerns of the modern age? The question has been agitating musicians, stage directors, audiences, and critics for decades. One response has been to create updated and creatively “interventionist” productions of works from the standard repertory — presentations that often try to “shake the dust” off of a work, to reveal the beating heart that speaks to us today.

An equally important response has been a spate of new operas that use stories ripped from newspaper headlines: John Adams’s Nixon in China, with its reenactment of Richard and Pat Nixon and Henry Kissinger getting off the plane and meeting Mao Tse-tung and Chou En-lai, or Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking, based on the famous movie about Sister Helen Prejean and a convicted murderer awaiting execution. Other recent examples include Mason Bates’s The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs and Jeanine Tesori’s Blue, which castigates police brutality against African American males.

The phenomenon is not entirely new. In earlier centuries, operas often addressed significant current events and trends, though often they threw a veil over the specifics by setting the plot in another land or an earlier century. Comic operas were allowed more leeway. Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro attacks (if not as bitterly as does the Beaumarchais play upon which it was based) the power that aristocratic males exercised over the women in their households. By contrast, a serious opera most often placed its action centuries earlier than the current day — indeed, frequently in ancient Greece or Rome.

What a surprise, then, to discover that one of the most accomplished Baroque composers, Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767), wrote a very fine opera based on events that took place a mere six years earlier — though safely in a far-distant land (Persia).

The opera is Miriways (1728), a work that was finally published almost 300 years after it was composed and first performed. It has now received a superb new recording.

If you didn’t know that Telemann wrote operas, you’re not alone. I hardly did either. But it turns out that Telemann ran the Hamburg opera house during the 1720s-30s, where he kept many Handel operas in the repertory. He wrote 35 or so operas himself for Hamburg and other cities, most of them now lost. Of the eight surviving ones, the best-known is the light-hearted Pimpinone, which has been recorded several times, even way back in the LP era.

Since 1967, the ongoing critical edition of Telemann’s complete works has published all eight operas, including the one under discussion here, Miriways. The previous recording of this fascinating work, made during stage performances in 2012, was hailed by critics. The present recording, equally fine yet also quite different, preserves a single 2017 unstaged performance given in Hamburg’s renowned 2000-seat Laeiszhalle (built in 1908).

Telemann and his librettist Johann Samuel Müller built their opera around events that had taken place in 1722 in what are now Afghanistan and Persia. The main figure is Miriways, a highly fictionalized version of the Afghani emir known to history as Mahmud Hotak. The librettist, misled by an unreliable German-language biography of Mahmud, gave him the name of Mahmud’s father, Mirwais Hotak.

An 18th-century illustration of Mahmud Hotak, the Afghani usurper of the Persian throne (1722), who is called Miriwais (German spelling Miriways) in the opera.

The confusion is understandable, because Mirwais (the father) had in 1709 led a successful revolution of Afghanis against the Persian forces that controlled Kandahar. In 1722 Afghan troops repeated the process on a grander scale, putting Mahmud (the son) on the throne of Persia in Isfahan. There Mahmud remained until toppled three years later. The German biography of the son (Mahmud) dubbed him “the Persian Cromwell,” creating a somewhat forced parallel with the renowned general whose forces, in the English Civil War, overthrew a repressive aristocratic regime (the Stuarts, under Charles I) and founded the Protestant-led Commonwealth. The opera’s complex plot does not allude to (relatively) recent events in English history as concretely as does the biography of the Afghani usurper of the Persian throne. But it does turn the latter (misnamed Miriwais, as I said—but now spelled with a y) into a benevolent Enlightenment-style ruler, who always seems to do what is best, such as forgiving his former foes.

The plot involves elements typical of Italian libretti of the day, such as two couples, in each of which the woman and man are kept apart by complex circumstances; plus an evil schemer (Zemir, a Persian prince), who wants the woman from one of the couples for himself. Though the work is labeled a Singspiel, it uses secco recitative. (In most works called “Singspiel” in the 18th and 19th centuries, spoken dialogue was the norm: Mozart’s The Magic Flute, for example.)

The usual string of arias is relieved by one duet, a few short choruses, a march labeled “in Persian style,” and several other orchestral movements. There were originally also some dances and a divertissement-style “entry” for a group of drunken people, but the music for all of these is lost.

The booklet contains the libretto in German and English. The translation is sometimes more idiomatic than the one in the aforementioned 2012 recording (conducted by Michi Gaigg). But it is full of typos. For example, “borw” turns out to be “brow.” Worse, the booklet lacks a synopsis. An essay summarizes the historical and literary background of the work and explains what the costumes and sets may have been like, but barely discusses the music.

So I’ll tell you: Telemann’s music here is a delight, often resembling, in style, appeal, and high craftmanship, what we find in Handel’s operas and oratorios. At first, because the recitatives are in German, I kept being reminded of Bach’s two (by necessity) rather grim Passion settings. But I eventually got into the spirit and enjoyed the exchanges between and among the various characters and their quite diverse emotions and reactions.

Telemann authority Steven Zohn, in an informative review of the published score (in the music-library journal Notes), has observed that the scoring is less colorful than in some of Telemann’s earlier Hamburg operas (fewer arias with a wind obbligato; only one accompanied recitative). Still, he notes, a chorus of Persians opens with a delightful horn duet, and a sleep aria for Nisibis is accompanied by “muted first violins and oboes d’amore with pizzicato strings.” Zohn helpfully points to several numbers that “suggest the exotic locale through repetitions of melodic and rhythmic figures, drone basses, and dissonant harmonies” — features that Telemann picked up during multiple trips to Eastern Europe and that recur in many of his purely instrumental works or movements (which are sometimes expressly labeled “Polish”).

I found the performance, by a renowned Berlin early-music orchestra under Bernard Labadie, vivid and enchanting. (Canadian-born Labadie is the founding conductor of the renowned ensemble Les Violons du Roy. He has become a much-loved conductor at Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society.) Labadie makes a point of introducing distinct contrasts of pace at unexpected places, such as in the middle of the A section of an aria. We are far here from the bad old tradition of doing Baroque music metronomically. Labadie adds some fun percussion (e.g., wooden sticks quickly hitting each other), as in Miriways’s first aria. And he takes the above-mentioned chorus (likewise here outfitted with unwritten percussion parts) so quickly that the horn players have to scamper. This is not “playing it safe”; I would instead describe it as “playing a work back to life.”

Some of the vocal soloists are heavenly, including four sopranos: Robin Johannsen as the oddly named Prince Sophi (the rightful claimant to the Persian throne, traveling in disguise); Sophie Karthäuser as Bemira (whom Sophi loves and who longs for him as well); Lydia Teuscher as the young widow Nisibis (in love with Prince Murzah, who is from the land of the Tatars); and Anett Fritsch as the self-serving Prince Zemir (who competes with Murzah for the love of Nisibis).

I flipped for Johannsen’s Marzelline in the René Jacobs recording of Beethoven’s Leonore. She lives up to my expectations, not least in the marvelously embellished da capo of Prince Sophi’s aria “Viel lieber zu erblassen.” I am equally taken with Fritsch, especially for her ability to negotiate the tricky syncopations of Prince Zemir’s Act 2 aria, “Die Dankbarkeit wird sich verplichten.”

Soprano Robin Johannsen. Photo: Pentatone

Some of the others in the cast are merely very capable and controlled, which already puts this recording far above the wobble-impaired level one hears in many standard-repertory opera performances and recordings nowadays. Several of the singers are, like the horn players, pressed by Labadie’s lively tempos (especially in coloratura passages), but the effect is generally more exciting than annoying. And, marvel of marvels, there is no applause except at the ends of acts.

I do wish that André Morsch and Michael Nagy (as Murzah) had fuller low notes. Conrad L. Osborne, in his book Opera as Opera: The State of the Art (which I reviewed for the Boston Musical Intelligencer) rightly decries “the disappearing low end” in operatic singing (and not just in low-male voices, his book emphasizes). I should add that it’s not just a question of vocal technique: nowadays singers often choose roles that lie a trifle low for them, perhaps so they won’t come to grief on the role’s highest notes. And this can leave them sounding thin and unsupported on the lowest ones.

I have sampled the previous recording and see why Barker liked it so much. It is smartly and rather straightforwardly conducted by Michi Gaigg. (I shall look for other projects involving her!) As so often in recordings of complete operas, especially when made during a performance rather than under studio conditions, some moments are stronger in one recording than the other and vice versa. The Gaigg is more complete and contains a more comprehensive booklet-essay. Each prints the libretto and a good English translation. Either recording will satisfy the most demanding fan of Baroque music and will engage the opera lover looking for something different.

Both recordings can be streamed on Spotify and other sites. (The entire Labadie recording is on YouTube for free, broken up into dozens of tracks.) If you subscribe to Naxos Music Library, you can download the libretto of the Gaigg recording, which will largely work with the Labadie as well. YouTube also has a recording, not currently available in CD form, conducted by Reinhard Göbel.

And, if you like what you hear, there are those seven other Telemann operas, most of which have now been recorded at least once, including Orpheus (conducted by René Jacobs), Der neumodische Liebhaber Damon, Don Quixotte, and the lighthearted Pimpinone. In their own way, each of them comments on human desire, frustration, fantasy, playfulness, courtship — topics that are evergreen (as fresh as today’s headlines), topics that music is so well suited to express.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts

Tagged: Academie für Alte Musik Berlin, Bernard Labadie, Georg Philipp Telemann, Miriways