Book Review: “Jack” — The Romance of Revelation

By Landry Harlan

A taboo interracial romance may not be groundbreaking material for fiction, but Marilynne Robinson’s spare conflicts are only the means to generate intimations of the profound in the everyday.

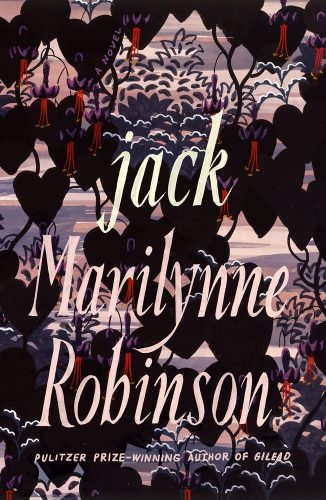

Jack by Marilynne Robinson. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 320 pages, $27.

Go here to buy at Bookshop.

Jack believes he is at his best “unseen.” He wears a black suit. He refers to himself as the “Prince of Darkness.” When we first meet him in Jack, he’s wandering around a graveyard in the middle of the night. He is suffering from the self-imposed exile of the Prodigal Son, previously referred to in Gilead, the Pulitzer-prize -winning first entry in Marilynne Robinson’s now four-part Gilead cycle. Told through a single letter from an old minister (John Ames Boughton) to his young son, that book revolves around the tense homecoming of the troubled Jack Boughton—named after John Ames—who has returned to Gilead with the hopes of soon bringing his Black wife and son there from St. Louis, where interracial marriage is illegal. As a young man, he left town after impregnating a woman, a sin that John Ames struggles to forgive throughout the novel. If only John could have read Jack, a radiant love story set during his years of exile that begins with an accidental overnight first date in that graveyard with the woman who could be his salvation: Della Miles.

Before we move on to the plot, it’s important to note that one does not need to have read the three prior books in the Gilead series to be swept up in this one. The novels don’t follow any sort of set linear timeline, but swoop in and out of each other; each illuminates parts of the others. Jack has always been Robinson’s most complex character, a welcome note of dissonance among the faithful. In Jack, his perspective and “incessable strangeness” finally get their due.

At first, Jack—a thief, drunk, and all-around “ne’er-do-well”—can’t believe Della recognizes him. They’ve met before—we learn how later—but the cemetery is poorly lit. The two must keep their distance because “he was disreputable and she was black.” He takes “little comfort from the fact that she could not see him well,” and constantly stumbles over his words, apologizing profusely. Yet, the English schoolteacher draws him out over the long, windy course of their conversation as they connect over a mutual love of poetry and Shakespeare. As time goes on, the two no longer keep their distance. The “Prince of Darkness” comes into the light where “she knew what he was and nothing was concealed,” excavating the tormented soul beneath the “bum” exterior. At 70 pages the scene runs on too long, but Robinson dramatizes the pair’s forbidden courtship in all of its charming awkwardness, even though we know the relationship is likely doomed once the sun rises and the cemetery gates open.

Dating in the open is an impossibility. Instead, the pair exchange books and glances, each trapped on an opposite side of post–World War II St. Louis, “parallel lines that would not meet.” Predictably, the relationship is assailed from all sides. No racial violence occurs, but the threat is omnipresent whenever the two are together. Della’s father, a Memphis minister, also strongly disapproves and urges Jack to leave her be. In between clandestine rendezvous, Jack agonizes through dark nights of the soul, stuffed full of Robinson’s signature spiritual musings. Sometimes he ends up at a church—atheist though he is—where he feels “not at ease, but at home.” These sections become repetitive, dense and tiring, missteps that contribute to making the author’s already slow-moving narrative move along at an even more leisurely pace. Without Della, the protagonist is a bore, incessantly wallowing in self-hatred and “Jackness, Jackitude, Jackicity.” We get it. He’s a mess. When the lovers unite, though, Jack and Jack come to life, Robinson’s tender prose deftly observing the twisting tether between two souls.

That said, though this is Jack’s story (if you couldn’t tell by the title), Della’s character is undernourished. Unfortunately, Robinson focuses her imagination elsewhere. We are never taken inside the character, and that makes it difficult to decipher exactly what is driving her to overcome society’s racial barrier and her family’s disapproval in order to make a life with Jack. She is set up to be too sharp a contrast with the bedeviled Jack; she is angelic in demeanor, but there is little nuance to her goodness. Perhaps a fifth book in the series, Della, will illuminate her inner life.

A taboo interracial romance may not be groundbreaking material for fiction, but Robinson’s spare conflicts are only the means to generate intimations of the profound in the everyday, to assert that the “common is somehow indeed the opposite of unremarkable.” Jack‘s central tension isn’t the specter of racism so much as the spiritual crisis of living with guilt and overcoming it. How to receive grace when it’s given, and believing you are worthy of it. In the cemetery, Della asks Jack if he’s ever noticed how striking a match in a dark room appears to spread far more light than if you strike it in a room that’s already lit. He jokes that the question sounds like a “sermon illustration.” Through the guise of a love story, Robinson transforms that illustration into Jack’s revelation.

Landry Harlan is a writer based in Cambridge. He has written no books, but will happily and honestly tell you what he thinks about yours.