Opera Album Review: A Terrific Recording of a Handel Pathbreaker — Powered by a Rock-Star Mezzo-Soprano

By Ralph P. Locke

Agrippina (1709), an enormous hit at the Met this past season, proves by turns gripping, sardonic, and exquisite.

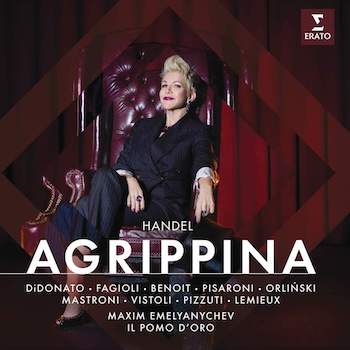

George Frideric Handel: Agrippina

Elsa Benoit (Poppea), Joyce DiDonato (Agrippina), Franco Fagioli (Nerone), Jakub Józef Orliński’s (Ottone), Carlo Vistoli (Narciso), Luca Pisaroni (Claudio).

Il Pomo d’Oro, cond. Maxim Emelyanychev.

Erato 0190295336585 [2 CDs] 231 minutes.

Click here to purchase.

Wow, another marvelous recording of a once-forgotten Handel opera! And it features Joyce DiDonato, who has become, over the past 15 years or so, one of the most prominent opera stars in the land, singing everything from Baroque to Donizetti to new and recent works by Jake Heggie. DiDonato has a flawless vocal technique but also superb communicative skills, and the combination makes her performances gripping—one can sometimes feel an audience holding their own breath as she bites into a phrase or wrings the pathos out of a soft note. Her communicativeness has also found other outlets: in concert tours with a chamber orchestra, and in the memorable interview that she did with Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and novelist Donna Leon at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC (viewable here).

Agrippina (1709) is not “just another” Handel opera but a pathbreaking work: one of Handel’s earliest (1709: he was 24!). Agrippina was composed for the largest of Venice’s eight opera houses (San Giovanni Grisostomo), which had five tiers of boxes totaling some 1400 seats. This is less than half the capacity of today’s Met (around 4,000 seats and standing-places). Lucky singers to perform in such a relatively intimate space!

The one surviving review (in a London newspaper) described the music as “the best that ever was heard” in an opera. Right on! The libretto is likewise among the best that Handel ever set, probably written by Cardinal Grimani (co-owner of the theater) some 20 years earlier.

The superb booklet essay by Handel authority David Vickers describes the plot as “a comedy of antiheroic characters with an unquenchable thirst for political and sexual power.” The two most positive figures are Poppea (seen here earlier in her politico-amorous career than in Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea) and Ottone (Otho), the heroic soldier whom she loves and, at the opera’s end, will marry. Agrippina (sister of the famously crazed Caligula) tries throughout the opera to clear a path to the throne for her son Nero, the maniac known later for his heartless and unpatriotic fiddling. In the process, she manipulates her husband Claudio (Claudius, the Roman conqueror of Britain) and three men in his employ: the freedmen Pallante and Narciso and the servant Lesbo. At the end of the opera, Agrippina is briefly caught in the web of intrigue she herself has spun, but manages to get Claudio to believe that all her actions were demonstrations of loyalty to him.

My condensed summary omits some moments imbued with comedy and social criticism, such as the extended scene in Act 3 in which Ottone, Narciso, and Claudio arrive one by one, each awaiting a secret assignation with Poppea. She hides them in three separate closets, then reveals their presence to witnesses—which of course particularly discomfits her war-hero husband.

The recitatives (perhaps somewhat trimmed here) communicate the tortuous goings-on efficiently, setting up the real meat: dozens of mostly short arias plus a few duets and larger ensembles. One delectable quartet for Agrippina, Nerone, and the two freedmen lasts a neat 40 seconds.

The arias are immensely varied in mood and in instrumentation: some use violins in unison, others two solo recorders, yet others just continuo. The emotions range from boastfulness (Claudio, in Act 1) to near despair (Agrippina, at the end of Act 2).

There have been at least eight prior CD recordings and five DVDs. And this does not count performances available only through audio- or videostreaming.

Performers in those previous recordings include such renowned figures as countertenors David Daniels, Philippe Jaroussky, Bejun Mehta, Drew Minter, and Derek Lee Ragin, and sopranos Véronique Gens and Danielle de Niese, under such conductors as Gardiner, Jacobs, Junghänel, Malgoire, and Östman. I have only briefly sampled some of them. (See YouTube or other streaming services.) But, after listening to this newest recording, featuring Joyce DiDonato and three virtuosic countertenors, I can confidently assert that, though some of those prior renderings may perhaps equal it, none surpasses it.

Joyce DiDonato in the MET’s production of Agrippina. Marty Sohl / Met Opera.

For one thing, the recording is relatively complete, going so far as to include, in an appendix, two passages that were not incorporated into the main sequence. (The opera exists in several different versions, all more or less authorized by Handel. The recording, as explained in the booklet, largely follows Handel’s first version.) A sense of the work’s dramatic shape and ideological aim is emphasized by the inclusion of a set of celebratory dance numbers near the end, when King Claudio’s happy rule over his kingdom is restored. This is not the actual music that Handel used in the first production (because that is lost) but five style-appropriate dance numbers that were found bound in with the autograph manuscript of another of his operas, Rodrigo (composed two years earlier).

Some readers may have been lucky enough to catch the Met’s recent production of Agrippina, starring DiDonato — either in the theater, on TV, or, recently, as generously streamed by the Met to help American opera lovers maintain their sanity. If so, they will readily remember that the roles of Ottone (the good guy) and Narciso (a fop) were taken by excellent countertenors, and the teenaged Nerone (i.e., the future Emperor Nero, already utterly crazed and self-obsessed) was played to the hilt by a swaggering Kate Lindsey (mezzo-soprano). By contrast, the opera’s original production had castrati in the roles of Narciso and nutty Nerone but a female mezzo or contralto as the brave, principled Ottone.

Here we have countertenors in all three roles. I mention this up-front because this may encourage or—the opposite—deter various potential purchasers. Some people can’t abide seeing, or even just hearing, a woman in a male role (though Handel and his audiences were happy with it). Others find countertenor singing, even at its best, too limited for the wide expressive range and contrasts of Handel’s music.

Fortunately, all three countertenors here are among the best currently active. As a result, the three (male) roles assigned to them are superbly well handled. Carlo Vistoli, least familiar of the three, imbues his exquisite soft high notes with a degree of self-satisfaction appropriate to Narciso. The character’s very name evokes the mythological figure (son of a river god and a nymph) who admired to excess his image in a flowing stream. Jakub Józef Orliński’s reading of the role of Ottone enhances his already-stellar reputation. In “Lusinghiera mia speranza” (Act 1, sc. 13), he varies the melody imaginatively upon the repeat, to keen effect. Though—a tiny gripe—the effects are so carefully rehearsed that they lack the illusion of spontaneity. Franco Fagioli is as astonishingly gifted a countertenor as the other two, but, on this occasion, lets the character’s franticness spoil his vocal delivery: notes are often spitted out fast but without a clear, full core to the sound, thereby depriving us of a firm sense of each successive pitch.

All the singers, in their different ways, project the specific intent of the words with precision and variety, and none of them forces the voice into ugliness. Joyce DiDonato is masterful in this (double-)regard, and Elsa Benoit shows Poppea’s ability to learn from Agrippina as the opera moves along, gradually trading sensitive sweetness for something much more canny and varied. Think I’m exaggerating? You can listen to each track for free on YouTube or the beginning of each of them here. Or watch the four-minute trailer with excerpts from the eight-day-long recording sessions.

The result of all this vocal and histrionic expertise is that, once one knows the bare bones of the plot, one can sense a lot of the action from the aural evidence alone. And, because the recording was made under studio conditions—which allow multiple takes of a given number or passage—much attention could be given to ensuring perfect intonation (even Fagioli is never off-pitch) and rhythmic coordination.

The low-voiced males likewise do well, and with voices appropriate to their roles: the conniving Lesbo is smooth as silk, whereas Agrippina’s heroic, devoted husband Claudio is played by Luca Pisaroni, whose sound is deeper and (by this point in his career) a little rough in production—not much, just enough to suggest the careworn character of the military general that he is. (Another small gripe: Pisaroni doesn’t quite command the roles lowest notes.)

The orchestra, consisting mainly of Italians, is colorful and vivid, presenting highly contrasted moods for each aria or larger ensemble. The players show admirable unity of intent and, throughout, are beautifully in tune.

Balances are excellent, within the orchestra and between the orchestra and the singers. The recording was made in the Mahler Hall, in the town of Dobbiaco, which is in the Italian Tyrol. In 2000 the hall was constructed inside a former hotel. (Dobbiaco—Toblach in German—is where Mahler composed Das Lied von der Erde and the Ninth Symphony.)

Joyce DiDonato as Agrippina and Matthew Rose as Claudio in Handel’s Agrippina at the Metropolitan Opera.

Are you the kind of listener who uses music as background to your daily routine? I often do this myself, and have learned that highly dramatic and incisive performances, such as we find here, are too distracting. Some of the recordings mentioned earlier might suit such listening better. But, if you’re looking for a sharply profiled reading of one of Handel’s richest and most varied operas, this new recording will give near-endless pleasure. It can be purchased as a CD, downloaded, or listened to on streaming services (e.g., Spotify). The thick booklet that comes with the CD is of course also available (as a PDF) to anybody who instead purchases it as a download or who subscribes (or whose library subscribes) to Naxos Music Library. Access to the booklet will enable you to follow every twist and turn of the fascinating plot and appreciate all the more the subtleties and nuances that these marvelous performers bring to one of the best operas in today’s operatic repertory.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Agrippina, Erato, George Frideric Handel, Joyce DiDonato, Met