Visual Arts Review: “Blane De St. Croix: How to Move a Landscape” — Facing the Horrific Sublime

By Charles Giuliano

The art of Blane De St. Croix comes at the viewer via a multivalent attack on the staggering challenges posed by irreparable climate change.

Blane De St. Croix: How to Move a Landscape. Through September 6 at Mass MOCA, 1040 MASS MoCA Way, North Adams, MA

Timed ticketing only. 413-662-2111, www.massmoca.org

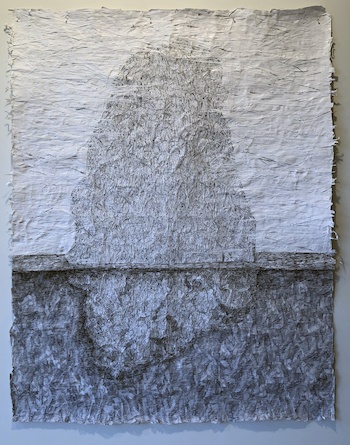

Dark Ice, 2014, ink on paper, by Blane De St. Croix. Photo: Charles Giuliano

Given the cavernous space of MASS MoCA, it was not difficult to observe the protocols of social distancing during a recent visit. We called ahead for a timed entry. On an August day, usually high season in the Berkshires, the contemporary art museum was populated, though somewhat less so than usual.

There was an hour allotted to the semi-permanent installations of the artist of light, James Turrell. There were a number of smaller pieces of interest, but we focused on two large galleries, each containing one work. As we gathered, a guide provided an overview of the pieces and their protocols. Given the tight time slot we were told to choose one of the two to examine. With a bit of luck, we managed to see both.

Six visitors were allowed into a room with a large oval of ever-mutating color projected on the wall of the enclosed space. The hues were primarily high chroma — with seemingly as many variables as swatches for paint in a hardware store. There were a couple of strobe intervals, which created retinal bounce. The impact of the space was soothing and meditative.

After waiting for another couple to finish, we just managed to enter the second gallery. Grasping a handrail we inched forward into a pitch-black space. There were two chairs where we experienced what could be described as an interlude of nothingness. The guide explained that, when our eyes adjusted, we would see some faint impressions. That didn’t happen for me.

Just as you enter the vast museum there are two floors of new exhibitions. We opted to report on the more compelling ground-floor galleries.

The art of Blane De St. Croix comes at the viewer via a multivalent attack on the staggering challenges posed by irreparable climate change. The diversity of this artist’s media and its ecological content — driven by a political mandate — evokes the tradition of Social Sculpture by the postwar German artist Joseph Beuys. The MoCA project How to Move a Landscape draws on dramatically different approaches to dramatize the rapid erosion and melting of permafrost in the Arctic.

The impressive diversity of work, from micro modeling to massive forms, generates considerable impact. What unites the eclecticism of the artist’s approach, visually and conceptually, is that a dauntingly complex phenomenon (the meltdown of a continent) is seen from a number of harrowing points of view.

Before we get into the primary content of the multigallery installation there is a sidebar. A long, narrow, waist-high diorama has been installed next to the staircase to the second floor. As we ascend, we are invited to look down on a miniature model of Trump’s border fence. This meticulously factual rendering carries a terrifying punch, filled with horrific humanistic aftershocks. One of De St. Croix’s concerns is the impact of borders. What do they contain and who is left out? From Hadrian’s Wall to the Great Wall of China, these epic follies of defensive enclosure are supposed to hold off the “barbarians.” Which is how cultures categorize Others–in this instance, undocumented migrants risking everything for a better life. Once you shake off your disgust, the sculpture stands as a metaphor for tragedy.

Another vision of eroding ice from Blane De St. Croix. Photo: Charles Giuliano.

The main ground-floor gallery is one of the most unique and challenging spaces in the museum complex. It is wide and narrow with vaulting headroom. Think of the nave of a cathedral without its columns. Its odd spatial footprint is a challenge to artists.

Here it has been configured masterfully. At the space’s center is a tilted, large white slab, perforated with several holes and supported by a single column. We can look at, under, and around it. There is an urge to touch and even soil this material. The artist encourages our yearning to touch; you can’t help but wonder how it is made. The first instinct is Styrofoam, but that proves to be wrong — it is some sort of mesh over an armature and plaster. It is meant to resemble a slab of melting ice.

Looking under it on the side and end walls are suspended vertebrae-like pieces. They abstractly evoke at-risk layers of permafrost. From a balcony on the second floor we are able to gaze down on a vertical armature with vectored segments simulating geophysical tectonics.

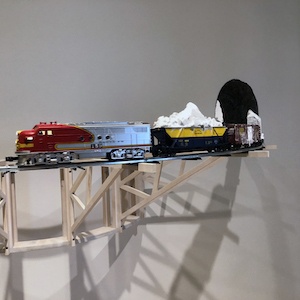

From there we were sent, careening billiards-like, through visual media. One experience entails watching a model train traveling a circular loop through a wall. It carries cargo of varied permafrost elements — heading we know not where or why.

Train carrying permafrost. Photo: Charles Giuliano.

A short film loop represents the artist’s 2019 journey to northern Alaska and an Iñupiat tribal settlement. The dim lighting reinforces a gloomy sense that the attempt to hold back erosion will be lost and eventually the community will be annihilated. Stacking up sandbags — as a replacement for melted permafrost — comes off as a dramatically desperate measure. The impact of the film is solemn and staggering because it provides a powerful vision of continental crisis. The video succinctly illustrates how indigenous people are facing the end of their precarious way of life.

Continuing on, there is a warren of galleries, each one featuring a work in a different medium that expands on the ominous ecological narrative. There are some wonderfully simple grisaille renderings of iceberg-like forms. One may appreciate them formally, but with a nudge as they morph into the show’s pervasive message about the dangers of global warming.

Another room has a massive freestanding curved sculpture. One side displays the armature, the other an abstracted take on a simulacrum of permafrost. This single section signifies a part of what’s left of the whole. From there the tour terminates in a room of large drawings.

De St. Croix’s installation draws on the power of contemporary art to entice the eye with dazzling legerdemain while at the same time leaving us with what, in another era, critic John Ruskin proclaimed as “truth to nature.” The artist updates this mantra by making us face the horrific sublime of reality.

Charles Giuliano is working on his seventh book, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: 1970 to 2020 an Oral History. He publishes and edits Berkshire Fine Arts.

Tagged: Blane De St. Croix: How To Move a Landscape

Charles, thank you for this thoughtful piece on a profound issue. Blane de St. Croix is to be commended for tackling this subject that affects us all.

Charles:

This piece validates what I have always said about your work. It needs to be shared by one and all who appreciate the creative art forms you obviously are so skilled in. The plus in the piece allows you to drag us (me, at least) along on your journalistic adventure as you break through the barriers, that keep the rest of us from expanding our “art form” experiences – especially when it comes to art, galleries, museums, salons, etc.

Also, glad to see and hear that book number seven is percolating in that disciplined and creative brain of yours and is coming along.

Let’s talk when you come up for air. Let’s coordinate a day and time, okay?

Wasn’t it the wicked witch of the West who kept screaming ” I’m melting. !? Well, we’ve been experiencing triple digits here in ‘the Springs’ for the last two weeks between 110 to 118 degrees. It’s downright enervating , despite our A/C capability.

Best to you and Astrid,

Jack Rabbit (who is beginning to slow down a bit)