Classical CD Review: The Symphonies of Max Bruch — Getting the Attention They Deserve

By Jonathan Blumhofer

This is a conductor and ensemble that have the measure of Max Bruch’s style and voice well in hand.

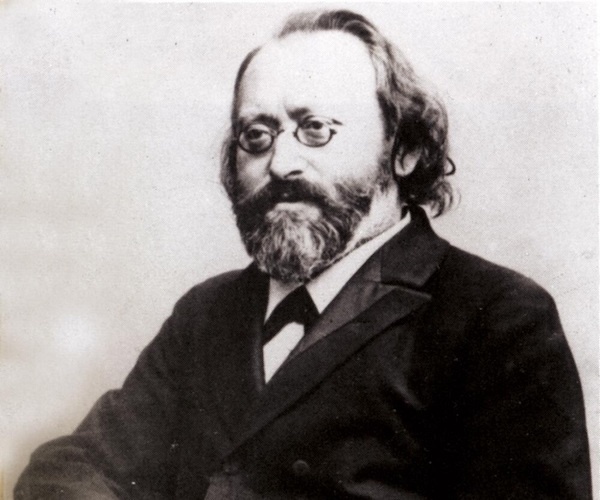

Lost amid Ludwig van Beethoven’s 250th birthday celebration this year is a slightly more macabre anniversary: the centennial of the death of Max Bruch. Granted, Bruch was no Beethoven. None of his considerable output turned Western music (or any other) on its head. And, even at his best, there’s a traditionalist streak to his writing that keeps him from being ranked among the 19th-century’s most influential composers.

Lost amid Ludwig van Beethoven’s 250th birthday celebration this year is a slightly more macabre anniversary: the centennial of the death of Max Bruch. Granted, Bruch was no Beethoven. None of his considerable output turned Western music (or any other) on its head. And, even at his best, there’s a traditionalist streak to his writing that keeps him from being ranked among the 19th-century’s most influential composers.

But is that a fatal flaw? I certainly don’t think so – and haven’t for a while. No, Max Bruch was a much better composer than his paltry reputation (which largely rests on the Violin Concerto no. 1 and Scottish Fantasy) might lead you to expect.

Yes, the influence of Mendelssohn and Schumann hangs heavy on his work (as they did on other symphonic composers of his era, including, sometimes, Brahms). But Bruch’s way with a melody was fully his own and his compositional technique more than proficient. Stylistically, he was very much of his day: Bruch’s music echoes and sometimes anticipates contemporaries like Bruckner, Dvorak, and Richard Strauss, among others. Indeed, it’s not too much to say that his symphonic output is compelling, as a new cycle of Bruch’s orchestral efforts from Robert Trevino and the Bamberger Symphoniker reminds.

Surprisingly, there aren’t too many sets of these symphonies on the market: just Kurt Masur (with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig) and James Conlon (with the Gürzenich Orchester Köln) have taped the full Bruch triptych. Richard Hickox’s partial cycle (the conductor’s untimely death precluded a recording of the Second Symphony), accounts of the first two symphonies by Michael Halász and the Staatskapelle Weimar, and a recording of the Third by the Hungarian State Symphony Orchestra led by Manfred Honeck fill out the rest of the (easily-accessible) discography for these works.

Of those, Masur’s Bruch is easily the most technically assured, though the 1970s engineering sometimes leaves a bit to be desired, sonically. Conlon’s conceptions of the outer symphonies are strong, though the Second proves a bit structurally wayward in his hands. The Halász album (on Naxos) is a welcome find, while Honeck’s Third (also on Naxos) is, to my ears, a bit stuffy. Hickox nails the Third and, if his take on the First doesn’t elevate its last two movements as much as it does the first two, well, that opening pair is magnificently done.

Where does Trevino fit among these pillars?

Well, his Bruch is consistently lyrical: Trevino clearly believes in the songful qualities of Bruch’s symphonic writing and his performances always veer in favor of the mellifluous and expressive. Accordingly, all three symphonies are played with a spaciousness that’s largely ingratiating.

Max Bruch was a much better composer than his paltry reputation (which largely rests on the Violin Concerto no. 1 and Scottish Fantasy) might lead you to expect. Photo: Wiki Commons.

The First, recorded here (for the first time) in its five-movement original version, soars. Its opening movement is spacious and colorful, beautifully blended, and, where called for (like the development and coda), intense and rhythmically tight. The second (cut by Bruch after the Symphony’s 1868 premiere) proves a lyrical, Mendelssohn-ian interlude. Trevino’s take on the Scherzo is roiling and boisterous, marked by lots of character but never driven too hard. The concluding pair of movements are, respectively, fervent and swaggering: the finale succeeds despite the fact that Bruch’s writing in it never lets go quite as much as one wishes it did.

Only in the Second does Trevino’s larger approach to Bruch cause some problems. Its first movement, especially, too often trudges, and the reading loses some sense of structural coherence as a result. That said, Trevino’s reading does play up the movement’s brooding, tragic atmosphere nicely and he draws some resplendent playing from the Bambergers in the central Adagio. In the finale, his tempos are broader than Halàsz’s (who rushes through the thing) and brisker than Conlon (who draws it out, frustratingly); the reading is warmly played and strongly shaped, though it lacks some of the visceral thrill Masur found in its pages.

Trevino tackles Bruch’s Third Symphony much as he did the First: its opening movement wants nothing for space (in the introduction) or amiability (in the spirited, but graceful, account of the Allegro vivace that follows). There’s lush playing galore from the Bambergers in the glorious second movement, while the third is suitably brawny. Best, though, is the finale, in which Trevino balances Bruch’s competing demands for songfulness and rhythmic energy; the concluding bars are as well-balanced and triumphant as they come.

Perhaps the most striking feature of Trevino’s Bruch cycle is his insistence that the three symphonies be viewed as three parts of a cyclic whole, rising from the E-flat-major First to the F-minor Second and culminating in the E-major Third. Granted, fourteen years separate the first and last installments, but the consistency of Trevino’s conducting here makes the argument seem more plausible than not.

Conductor Robert Trevino. Photo. Lisa Hancock.

What was Bruch doing in that decade-plus between the Second and Third Symphonies? Trying his hand as a theater composer (among other things) and so, as a link, Trevino’s set is filled out by orchestral excerpts from three of Bruch’s stage works: Hermione, Die Loreley, and Odysseus. The five extracts provide a welcome glimpse of Bruch’s “other” career. Ultimately, though, they prove that he wrote more naturally for the concert hall than the stage.

In the Odysseus Prelude, echoes of Loghengrin, Mendelssohn’s Meerestille und glückliche Fahrt, and even Bruch’s Second Symphony abound. But the piece has little sense of proportion, lasting about a third longer than it needs to, rehashing ideas already presented and thoroughly developed.

The Prelude to Die Loreley is a rather better effort, full of unexpected harmonic and metrical turns, though it runs a bit on the shorter side, especially given the contrasting materials in its second section that are left underexplored.

Best are the Prelude, Funeral March, and Entr’acte from Hermione. Beautifully scored, defined by soaring melodies and stirring episodes, they suggest a composer truly inspired by his subject matter (in this case Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale).

In all of these fillers, Trevino draws playing of heat and full-bloodedness from the Bambergers (the big brass refrains in the Hermione Funeral March are conspicuously fine). This is a conductor and ensemble that have the measure of Bruch’s style and voice well in hand. Accordingly, they give these pieces precisely the sort of sympathetic and sonically robust performances that they demand.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.