Rethinking the Repertoire #18 — Max Bruch’s Symphony no. 3

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the eighteenth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

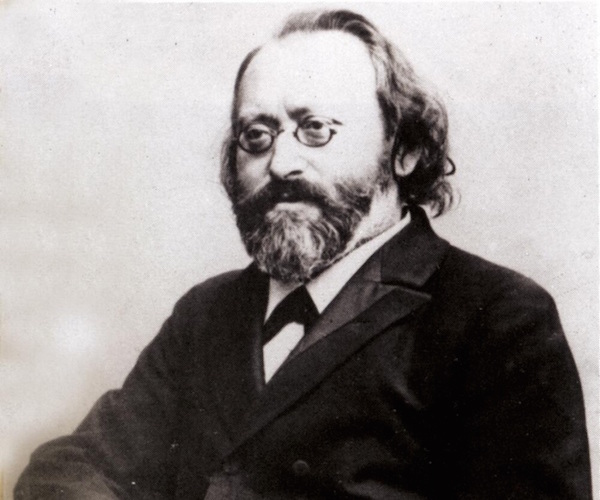

Composer Max Bruch — a good deal of the neglect of his music owes to his reputation as a conservative.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

You’ve got to hand it to Max Bruch (1838-1920): when he found something, stylistically, that worked for him, he knew it and he ran with it. How else to explain his half-century-long career writing music in the harmonic idiom of the G-minor Violin Concerto? Of course, there’s nothing wrong with doing something like that, provided you don’t simply turn out the same piece over and over again. And Bruch didn’t. His saving grace was that, while he might not have been an earth-shaking composer, he was a great tunesmith, a smart orchestrator, and an inventive tinkerer with form.

His much-loved Violin Concerto no. 1 demonstrates all of these tendencies. So do the Scottish Fantasy and Kol Nidrei. And, though they’re played with far less frequency than the First Concerto, Bruch’s succeeding two don’t simply sit on their predecessor’s laurels but strike off in some peculiar directions, particularly the epic endurance test that is the Third.

Bruch’s three symphonies are cut from similar melodic cloth but hew mainly to familiar models. The First, written in 1867, owes a clear debt to Mendelssohn and Schumann, though its own personality emerges regularly, especially in the devilish second-movement scherzo with its brusque shifts from major to minor and back again

Just a couple of years later came the Second, which takes a three-movement form built around a deeply-felt middle Adagio. The finale offers a tune that Bruch’s friend Johannes Brahms seems to have drawn on for the last movement of his own First Symphony (which wasn’t finished until six years later). Bruch’s Violin Concerto no. 1 also seems to have been one of Brahms’s models in crafting his own Concerto in 1878

More than a decade separates the Second Symphony from the Third, but Bruch’s earlier stylistic fingerprints remain recognizable. He wrote the piece in the early 1880s, towards the end of a short, unhappy spell as conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society, and at the request of Walter Damrosch’s Symphony-Society of New York.

Parts of it are infused with nostalgia. Bruch evidently considered subtitling it “On the Rhine” and there’s a pronounced sense of longing and reminiscence in many of the extended gestures and even whole movements (like the slow second). The Third is a beautiful piece, yes, thoroughly of its time and perfectly conventional, but conventional in a way that’s steeped in its composer’s distinctive style and made fresh by a crafty handling of forms, a strong ear for instrumental color, and a great sense of how to build (and resolve) a musical argument

Its first movement opens with a warmly lyrical introduction that brims with Wagnerian allusions: you could almost be forgiven for thinking you’ve fallen asleep and woken up in the middle of Siegfried – that is, until the tempo picks up and the movement proper gets underway. Here, we’re firmly planted in the graceful, songful Land of Bruch, with its lush tunes and intricate counterpoint. Throughout, the mood is amiable and, at times, things get rather spirited. Shadows are largely absent, though: when they come, they pass quickly, hardly obscuring Bruch’s warm sun.

It’s the second movement that forms the Symphony’s emotional core. Bruch’s writing here is at its warmest and most Brahmsian: there are more than a couple of phrases that might have been lifted from any of that composer’s four symphonies. But, as was his tendency, Bruch had his own way with the melodic writing. It flows with a certain natural beauty, reminiscent perhaps of the Scottish Fantasy (penned just a couple years before this Symphony). The primary theme involves a gorgeous, yearning melody, full of leaping figures. Bruch spins this into a moving and remarkably concise statement, full of wonderful instrumental touches (like an early duet for horn and clarinet), allusions to folk music (he employed more than a few prominent drones), and an overriding melancholy tone.

The third-movement scherzo recalls, to a point, the brilliant second movement of the First Symphony, though it lacks the latter’s diabolical impishness. Here, in the scherzo sections, everything’s very jolly in a rather stolid, Germanic way – abrupt and whimsical. In the trios, Bruch lets loose a bit, with episodes of nimble scoring and Haydn-esque toying of phrase lengths.

For the last movement, Bruch returned to the bucolic mood of the Symphony’s opening half. Again, the writing is largely diatonic and the mood largely lacking in conflict. There are three main themes at work. The first is a songful tune that Bruch recycled and expanded for the finale of his String Quintet in E-flat nearly forty years later. Here, it leads to a martial refrain that seems to owe a clear debt to the finale of Brahms’s Symphony no. 2. This then develops into a leaping figure that recalls the second movement. This time, though, there’s nothing pensive about it: the music is almost giddy and drives to a syncopated climax.

Structurally, this finale is perhaps the least successful movement of the Symphony. The ways its themes interact and build towards the end can feel kind of forced. And at some points (the last couple pages of the score, for one), you wish the music might leap off in a new, unexpected direction for some sort of fresh revelation. Even so, it’s hard to argue with the overall excitement of the music — which doesn’t outstay its welcome — and Bruch’s excellent writing for the orchestra: the whole ensemble is showcased to brilliant effect.

A good deal of Bruch’s neglect owes to his reputation as a conservative, which too easily can be equated to mean that he wasn’t a good composer. His music, though, doesn’t bear that out. It’s smart, strong, crafty, and, often, quite endearing. As Philip Huscher’s noted, Bruch was interested in writing for audiences of his day, not for posterity – and he did that quite successfully.

To the charge that Bruch’s works can come across as stiff and forced, well, that’s an argument that can be made. But it can also be aimed at Beethoven and Brahms and Schumann. And, at some point or other, pretty much every other composer in the canon. For my money, Bruch’s strengths overshadow his flaws, both the invented ones and those that can be proved. His is a body of music worth knowing if only because it’s all well-written and, much of it, thoroughly enjoyable. Ultimately, it deserves better than it’s gotten in the near-century since Bruch’s death.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

I love reading about the genius of a classical composer’s symphony with a new insight shared.

I just finished listening to the three Bruch symphonies performed by Masur and the Gewandhaus Orchestra. I am not a musicologist but I’ve listen to a lot of classical music over my 65 year lifetime so I think I have a good sense as to what’s what. I love the 19 century romantics and I’m always looking to hear the ones that I’m less familiar with. In my opinion the first symphony truly is warmed over Mendelssohn and Schumann but not done nearly as well. Recently I can’t get the coda from the Scottish Symphony out of my head, it wakes me up in the middle of the night! There is nothing in these Bruch symphonies that nearly reach that level. The second symphony to me is a big fat lump of coal. It just kind of lays out there with sound coming towards you and no particular direction. The third symphony, written many years later, has much more going for it. Very creative, lyrical and enjoyable to hear. None of them reach the heights of the G minor violin concerto or Scottish fantasy. I wonder why?