Book Review: “Crooked Hallelujah” – On Mothers and Daughters

By Melissa Rodman

Crooked Hallelujah is an engaging debut, its intricately structured narrative following four generations of a matriarchal family from the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma.

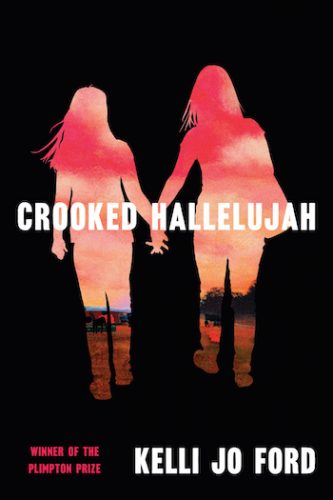

Crooked Hallelujah by Kelli Jo Ford. Grove Atlantic, 304 pages, $26.

A link on writer Kelli Jo Ford’s website leads to a writing exercise entitled “How to Avoid the Mirror in Character Descriptions.” Using her 2016 short story “You Will Miss Me When I Burn,” (published in the Virginia Quarterly Review) as an example, the task on the blog advises writers that they should work to construct characters that look beyond reflective surfaces. A reader must be able to visualize characters — not via their own gaze but in action, and through others’ eyes.

“You Will Miss Me When I Burn” is one of the thirteen intertwined pieces that make up Ford’s engaging composite debut, Crooked Hallelujah, which follows four generations of a matriarchal family from the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma: Granny, Lula, Justine, and Reney. Over a few decades, these women push and pull away from each other, ideologically and geographically, as their various struggles, beliefs, and understanding shift and converge. Ford filters the trials and tribulations of these characters through a kaleidoscope ,not a mirror. “Can I love anything the way that I used to love the mystery of my mother, her strength in suffering?” Reney concludes late in the novel. The question could be asked of each of the narrative’s pairings, as great grandmother-grandmother-mother-daughter patterns whirl about in transformation.

The volume’s fluid perspective encourages the generational swirl. Some pieces are written in the first person — with different characters operating as “I” — while others are propelled by third-person narrration. Indeed, many of the chapters were first published as individual stories (the piece “Hybrid Vigor” won The Paris Review’s 2019 Plimpton Prize). Reading them collected here rounds out our view of the characters as well as the places they travel to and through. But it also requires that we let the intricate text unfold. At times, our viewfinder has to be adjusted.

Taking the stories together invites us to superimpose how Justine, both a teenage daughter and mother-to-be in the opening chapter, sees her daughter, Reney, and how Reney sees Justine. “She’d lived exactly half her life doing all she could to make sure my life was better than hers,” Reney muses as a teenager herself. “After taking stock of all the ways we matched and saying, ‘Good night my Tiny Teeny Reney,’ she’d hold me close and whisper, ‘Don’t be like me. Don’t ever be like me.’” Justine’s mother, Lula, also nicknames Justine “Teeny,” further layering the characters.

Later, though, Justine grapples with Reney’s divergence:

In Portland, Reney was taking on debt to study books she could have read for free, as far as Justine could tell. Her Reney, who after high school had become such a hard woman, so cautious with money and closed off. Sometimes it seemed this kid she’d more or less grown up with, the girl she’d loved and fought with and rocked in the night — her daughter, her very soul — was a whole different person.

Ford sketches the novel’s core four women not only by approaching them from assorted familial angles — as in these passages — but also by introducing people and stories who are a step or two removed from them. “You Will Miss Me When I Burn,” for instance, revolves around a father-son errand featuring Justine’s husband, Pitch, and her father-in-law, Ferrell, as Ferrell faces an impending wildfire and considers how to save his horse. Here, and notably in the story “Then Sings My Soul,” which focuses on new neighbors of no relation to the protagonists, Justine becomes a passing reference, her back-and-forth between Oklahoma and Texas contextualized in fuller accounts of Pitch’s, Ferrell’s, and the neighbors’ charged experiences in the latter state.

As Justine and Reney’s orbit takes them in new directions, both together and apart, they are tethered to Granny and Lula, their roots in Oklahoma. Parent-child analogies are woven throughout the stories, serving as thematic anchors. “You’ve got to keep moving, whatever you do, but when I get around Mama, my movement’s all in reverse,” Justine says, referring to Lula. In turn, Reney places her mother at the malleable gravitational center of her memory: “Her: equal parts beautiful optical illusion and fiery hot star. And me: an imperfect planet she kept as close as she could.” Both the book’s intricate structure and the fiery glint of its language pay homage to the orbits that matter.

Melissa Rodman writes on the arts, and her work has appeared in Public Books and The Harvard Crimson among others.