Film Review: “WBCN and the American Revolution” …. The Revolution Continues

By Adam Ellsworth

‘BCN left behind some big shoes, but they can be filled. And there are inspiring signs that the kids, not the grizzled veterans of last century, will do the filling.

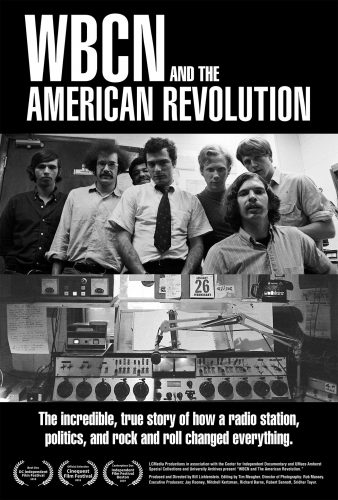

WBCN and the American Revolution, directed by Bill Lichtenstein.

Do any reading about Ray Reipen and you’ll likely come across the term “hippie entrepreneur.” It’s an appropriate enough description considering the fruits of his entrepreneurial spirit, though Reipen certainly never looked like a hippie. When he moved from Kansas City to Boston in 1966, Reipen was already 30, had short hair, and liked to wear three-piece suits. He looked like the lawyer that he was. In fact the reason Reipen came to Boston in the first place was to earn a graduate degree from Harvard Law School.

In his first year living in the Hub a client from back home who had also relocated to the city let Riepen know that the Ford Foundation was planning to fund a Boston branch of Jonas Mekas’s Film-Makers’ Cinematheque. The funds were on their way, but as they hadn’t arrived yet, Reipen was asked if he would front the money to cover the lease on an old Unitarian Meeting House on Berkeley Street that would house the project. Riepen agreed. A few weeks later the client called to tell him that the Ford Foundation money wasn’t coming after all, and Riepen’s temporary investment had just become a lot less temporary.

Since there was no turning back now, Reipen figured he might as well try to make the most out of his money. He knew avant-garde films weren’t going to provide the cash flow necessary to keep the new venture afloat, but he did have an idea that might work. If there’s one thing Boston had (and still has), it’s college students, and in the mid-1960s, college students listened to rock and roll. So how about open a rock club? And with that the Boston Tea Party was born.

The Tea Party only lasted three years, but that was all the club needed to cement its legacy as Boston’s most famous and important rock venue. It offered a place for local bands like the Hallucinations to play, while also serving as a home away from home for the Velvet Underground (the rest of the world thinks of the Velvets as a New York band but Bostonians know better), and the point of entry for new groups out of England like Led Zeppelin.

A year after the Tea Party opened, Reipen turned his attention to radio. At that time, “radio” meant Top 40 AM, with over-the-top DJs playing the same songs over, and over, and over again. A lot of those songs were actually pretty great, but they hardly told the whole story of mid- to late-’60s rock music. So once again, Reipen turned his attention to the kids. He knew college kids weren’t concerned with the latest 45 single. They were into albums. Why not start a radio station that played the music college students were buying at record stores? And how about limiting the amount of advertising on the station and featuring DJs who spoke to listeners in conversational tones?

Reipen took this idea to a national radio convention, where everybody he talked to told him to stick to being a lawyer, because this was the dumbest thing they’d ever heard. He went ahead anyway. Reipen started by looking for a local radio station that was in financial trouble, figuring he could convince them to let him try something new. He landed on WBCN, a struggling classical music station sitting at 104.1 on the FM dial, and talked his way into a takeover of the 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. time slot.

To launch his experiment, Reipen again turned to the kids. He visited college radio stations to recruit the DJs. Tufts student Joe Rogers (going by the radio name “Mississippi Harold Wilson”) was among the chosen, and he was in the chair at 10 p.m. on March 15, 1968, to fire the opening shot of what Reipen was referring to as “The American Revolution.” Rogers began with a cut from Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, followed by Cream’s “I Feel Free.”

By May 1968, Reipen’s dumb idea had completely taken over WBCN and was on 24 hours a day. It wasn’t long before the “professional” DJs started calling, asking for jobs and saying they could do better than the kids Reipen had on the air. Reipen wasn’t interested.

“Somehow, Ray came to the conclusion, made the decision, that he was going to stick with the kids,” Joe Rogers remembers in the extraordinary new documentary WBCN and the American Revolution. “It was a crazy decision, but that was it. Everything followed from that decision.”

The “everything” that followed is the focus of WBCN and the American Revolution. Directed by Bill Lichtenstein, the film — which masterfully mixes archival audio and video content with original interviews — has been a decade in the making, and now that it’s complete, its release has been upended by COVID-19. Thankfully, the doc is available for streaming via its website. Even better, viewers have the opportunity to support a community radio station or independent movie theater when they rent the film.

Of course the music on ‘BCN had to be top-notch, or nothing else would matter. But the station wasn’t dubbed “The American Revolution” solely because of the musical tastes of its DJs. From the beginning, the station was involved socially and politically. It was obviously the time for it. Less than a month after Reipen and Co.’s takeover, Dr. King was assassinated. Two months later, Bobby Kennedy was killed. Two months after that, the police rioted against antiwar protestors outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The same college kids listening to WBCN were worried they’d end up in Vietnam, fighting a war most of them thought was immoral and criminal.

‘BCN offered listeners the tunes they wanted to hear, as well as a take on the news of the day they weren’t likely to get elsewhere. Folks like Danny Schechter “The News Dissector,” were legit journalists, but they didn’t let “objectivity” get in the way of explaining to the audience how the government was lying to them about the war in Vietnam (Schecter was interviewed for the film before his 2015 death, and he appears throughout WBCN and the American Revolution). The station even paid for a skywriter to create a giant peace sign above Boston Common during the 1969 Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam protest.

From the beginning, the station and its listeners were part of the same community, so much so that early on WBCN created a volunteer-staffed Listener Line. The service mostly existed to assist listeners with the relatively trivial, such as where to get a good pizza, but at times the volunteers found themselves doing truly important work and calming callers who were threatening to kill themselves. This sense of community extended to the advertising on the station. If there was a product ‘BCN didn’t want to be associated with, or the station didn’t feel was right for its listeners, it would simply refuse the ad and the money that came with that marketing, much to the shock and confusion of the prospective advertisers.

Righteous as the station was, it was also far from perfect. DJ Charles Laquidara is one of the true heroes of ‘BCN history (and all of Boston media history for that matter), but it was not his finest moment when during a public service announcement for Project Place’s Drug Dependency Treatment Center, he ad-libbed, “If you’re a chick and you can type, they need typists.”

Soon after, a group of women showed up at the station with a box full of literal baby chicks and dumped them on a desk. The animals were chicks, the protestors said. They were women.

In the end, the creative protest paid off and WBCN gave air time to the women’s liberation organization Bread and Roses. It also dawned on the station’s brass that perhaps they needed some female DJs, which led to the hiring of the legendary Maxanne Sartori. Maxanne had some of the best ears in the business, and it was she who broke Aerosmith and introduced Queen to America.

Bob Slavin, Bill Lichtenstein, and Norm Winer at a screening of WBCN and the American Revolution. Photo: Ron Pownall.

By accident, ‘BCN also found itself well ahead of the curve on gay rights via its airing of the “Lavender Hour” on Sunday nights. Hosted by John Scagliotti, the Lavender Hour was, as the name would imply, only 60 minutes long and only broadcast once a week, but it was the first show of its kind on commercial radio, and certainly the only time the station played disco. The show only started in the first place because there was some low-rating air to fill on Sunday night, so Scagliotti, who otherwise worked in the station’s news department, got the chance to play DJ. What he created was a lifeline for the region’s gay community.

It would be unfair to say that by the mid-’70s, ‘BCN was “just another radio station,” but it’s certainly true that as the Me Decade progressed, the station was no longer taking part in a revolution. Lichtenstein ends his film at this point, with the golden age drawn to a close. First, though, he highlights the live broadcasts ‘BCN showcased in the early- to mid-’70s. Lichtenstein lingers on a 1976 performance by Patti Smith that the station broadcast live from the Jazz Workshop. During the performance, Smith began an impromptu, part-sung, part-spoken poem about the power of radio, and how that power was being weakened by censors who wouldn’t allow her to say certain words on the air. They were just words after all. With that, she started saying those words over the airwaves. Our hero Joe Rogers, still with the station, was at the studio and had the authority to cut the broadcast. Despite the expletives, Rogers decided not to pull the plug.

“If that doesn’t quintessentially sort of package up ‘BCN’s essence, stuff like that, on the radio, wow, amazing,” the DJ Tommy Hadges crows in the film. “Never happen again. Never. Happen. Again.”

It’s true that most stations would have killed the broadcast. Most stations wouldn’t have been broadcasting a Patti Smith Group concert in the first place. Still, Hadges’s comment is the film’s one bum note. Why could such a thing “never” happen again? And if it really couldn’t, then why does Hadges seem so happy? Surely we aren’t meant to believe that WBCN’s revolution was the final revolution. Surely the film’s takeaway isn’t supposed to be that the rebellion of the ’60s is impossible to repeat so don’t bother trying. ‘BCN left behind some big shoes, but they can be filled. And there are inspiring signs that the kids, not the grizzled veterans of last century, will do the filling. The revolution continues.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.

Tagged: Bill Lichtenstein, Charles Laquidara, Danny Schechter, documentary