Dance Commentary: Sally Banes (1950-2020)

By Marcia B. Siegel

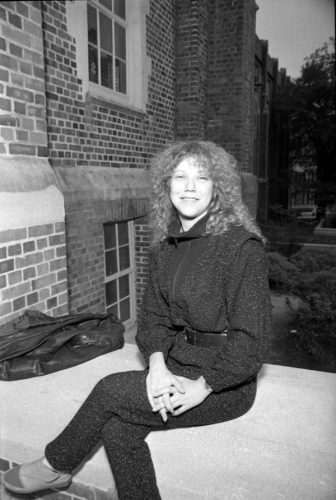

The late Sally Banes. Photo: WikiCommons

Dance critic, scholar, performer, activist Sally Banes died on 14 June in Philadelphia. She was not quite 70. She’d published eight or nine books and countless reviews and essays, had taught in universities and workshops, performed and danced and proselytized through the golden days of postmodern dance. All that in less than three decades, before she was felled by a debilitating stroke. The astonishing range and productivity of this record strikes me now, as it did at the time.

Like the death of anyone close to you, Sally’s takes me back through my own years, viewing the vanished people and performances we went through together, and on different but concurrent tracks. Some of those reflections appear in the tribute below, which I gave some months after Sally was hospitalized in 2002. It was at a conference of the Congress on Research in Dance (CORD) in New York. She’d won the year’s award for excellence in dance scholarship. The talk was televised and broadcast to Sally’s room:

For this talk, I decided to contact a few writers and colleagues and include their thoughts as well as my own. One thing I’ve always liked about Sally is her groundedness in the real world. She didn’t just think about performance — she went all over the place to see it. She knew the dancers and performed herself on occasion. Just about everyone I talked to mentioned her need for first-hand experience.

Janice Ross remembers Sally in the late ’70s, starting out to study break dancing. To find the real thing, she headed out late at night, to remote street-corner addresses she’d heard about, a mission that might have intimidated a less determined individual. Janice says she was fearless about plunging into movement physically.

I seem to have always known about Sally’s diabetes—she carried it lightly. Peggy Phelan thinks it was her chronic disease that made her interested in everything about the body, including dancing. She told Peggy last year about her latest project, on olfactory performance. As part of the research she enrolled in a course in how to create scents. She got a C in her “aroma composition” project—the teacher judged the perfume to be too sweet. This convinced Sally she had to take the next part of the course.

I knew her first as a journalist. She wrote and sometimes edited at the Soho Weekly News in the late ’70s, and we were frequent companions in trying to bring some order to the chronically disintegrating Dance Critics Association. Robert Greskovic sensed that she always had her ears open for people who were in a position to take on assignments. She heard somehow that he was going to see an important ballet out of town, and convinced him to review it for the Soho News. This was the beginning of his regular writing for the paper.

What I didn’t know was that around this time she was also studying for her doctorate in Performance Studies at NYU. I joined the faculty there in ’83, but by then she was just about finished with the dissertation that became Democracy’s Body, on Judson Dance Theater, performance, and culture. Terpsichore in Sneakers, which was on its way to becoming a classic document of the postmodern dancers, came out in 1980.

Now I see how thoroughly informed her work is by the three professors who shaped the interdisciplinary program at Performance Studies in its early days. Michael Kirby’s insistence on scrupulous and “objective” documentation and description. Richard Schechner’s connection with the avant-garde as a practitioner-director, and his perception that anthropological theory could be applied to the study of performance. Brooks McNamara’s embrace of popular culture, both in historical and contemporary terms.

Sally chose her subjects skillfully — her territory extended from postmodern New York to revolutionary Russia, and her medium ranged from writing to teaching to filmmaking. But I’ve never felt she was a dabbler. She researched deeply, and, as Janice says, she prized readable scholarship. Her 1994 collection Writing Dancing in the Age of Postmodernism is full of wonderfully put-together gems like the piece on Fred Astaire’s drunk dances, and the thought-provoking analyses of dance writing itself.

I was astonished and a little envious of her prodigious energy and her terrific ability to conceptualize an original project and persuade the necessary people to sponsor it, and then to find enthusiastic collaborators to work on it with her. These are qualities that make for a successful academic career, but with Sally, the projects always have had bigger implications than her own professional advancement.

She persuaded Yvonne Rainer to make the Trio A film in 1978 because she wanted that dance on record for posterity. She proposed a study of the elephant ballet Circus Polka when she found out the “Popular Balanchine” project hadn’t considered it. She did a seminar on Kasian Goliezovsky for the DCA in 1986, when people were starting to take an interest in George Balanchine’s early influences.

Peggy Phelan noted that she’s been dedicated to the project of building bridges between dance and the other disciplines, attending

conferences, doing panels and papers, tirelessly demonstrating dance’s connections to the other performing arts.

I loved the way she delivered speeches, often being matter-of- fact while throwing outrageous challenges to the audience. She was political — not just in an intellectual way. She said what she thought, as an old lefty who believed you didn’t just ponder about badly paid workers or under-represented minorities, you were supposed to do something about it.

Mindy Aloff sent me these thoughts about her first encounters with Sally at the American Dance Festival:

“Sally was very young–maybe 22 or under?–at the Critics Institute that summer. She was also the special assistant or intern to Deborah [Jowitt]. The first thing I remember about her is how she looked. She had a better figure than many of the dancers and certainly better than any other participant in the Critics Institute! She also had that head of Renaissance, straw-colored curls, which gave her a deceptively cherubic look. She liked to wear hot pants (it was extremely hot in Connecticut the summer of 1977) and flip-flops; she had one pair of bright red hot pants, which looked fabulous with her coloring. And she loved to go out dancing, especially the salsa.

I remember how, even then, she had started to study Judson. I was amazed that she wanted — and felt able to — do this without ever having seen any of them in their youthful heyday.

Oh no, she was absolutely sure that they were great (she was especially puzzled that Lucinda Childs had never gotten her due), and she just KNEW that she could write a book. The assurance was prodigious.

I also vividly remember a sample review she wrote about Balanchine’s Valse-Fantasie (the one from the ’60s, maybe ’67): “We know [from the way the principal couple exit at the finale] that they will never meet” was Sally’s last line, or something very close to her last line. I had never considered the ending of Valse-Fantasie, and her perception changed forever the way I looked at the ballet.

I also vividly remember a sample review she wrote about Balanchine’s Valse-Fantasie (the one from the ’60s, maybe ’67): “We know [from the way the principal couple exit at the finale] that they will never meet” was Sally’s last line, or something very close to her last line. I had never considered the ending of Valse-Fantasie, and her perception changed forever the way I looked at the ballet.

She spoke about her family, of which she was fond, and, very matter-of-factly, about her diabetes and her daily treatments for it. Her matter-of-factness was extraordinary. It was clear, even then, that she was destined to do great things.”

For me, more than 25 years later, I treasure the endless curiosity in Sally’s writing — and its disinterestedness. She doesn’t beg you to love something or hate something, even when she’s raising your consciousness. She asks you simply to pay attention. She makes me think about dancing and dance history in new ways. She makes me think about dance writing as something that can rise above the automatic, the inevitable, the intuitive, and about my own writing as something I can always improve on.

Like choreography, published writing seems fixed and finished — okay, it’s done, now we can move on to something else. Sally’s work shows us that writing can have its own continuity, and maybe that’s the most important thing of all.

We love you, Sally.

2 August 2003

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at the Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for the Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. She has contributed two selections to Dance in America, the latest edition in the Library of America’s “Reader’s Anthology” series. Her 2006 book, Howling Near Heaven – Twyla Tharp and the Reinvention of Modern Dance, has been reissued in paperback with a new introduction, by the University Press of Florida.

While it’s always good to see my name in print, positively, I’d like to take this space to clarify the point being made about Sally Banes’s asking me to cover a premiere I was planning to see in Washington, D.C. for the dance section of SOHO NEWS. That part is accurate; what is not accurate in the telling above is that this request, which I accepted, “was the beginning of [my] regular writing for the paper,” which would have been in 1981. I began writing for what was initially the SOHO WEEKLY NEWS in 1974, and published there at first with some regularity and eventually more off than on. By ’81 I hadn’t written for the paper in a while, so I was pleased and interested to learn from Sally that I might do so again, which I did, when she saw to it that my review of The Wild Boy with ABT got published on the pages she was then editing. Meanwhile, greetings and salutations, to you Marcia.