Visual Arts Commentary: Boston’s Historical Memorial to Black Lives Vandalized

By Mark Favermann

Boston’s most celebrated piece of public art was one of 16 monuments irresponsibly defaced during the recent protests.

The Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Bronze Relief, 1897, with architectural elements by Charles Follen Mckim. Photo: National Park Service.

What many consider to be America’s greatest public monument, the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial, was thoughtlessly defaced in Downtown Boston on May 31 during the protests against George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer. This beautiful bas-relief has been vandalized before – once with paint in 2012, and the sword was broken off in both 2015 and 2017. Created by the gifted sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, it is set across the street from the Massachusetts State House on a wall on the edge of the Boston Common. This celebrated piece of public art was one of 16 monuments irresponsibly defaced during the protests.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907) created this masterpiece at the end of the 19th century, a time when racial prejudice, hatred, and abuse was on its ascendancy. This sculptural homage to black heroism was a visual rebuke to the racial bigotry of the Jim Crow period. From the 1880s into the 1960s, a majority of American states enforced segregation through “Jim Crow” laws (the name of a popular blackface character in minstrel shows). Throughout the country, many states and individual cities imposed legal punishments on people for consorting with members of another race. The most common types of these restrictive laws forbade intermarriage and ordered business owners and public institutions to keep black and white clientele separated in public accommodations, schools, and even transportation.

Created by perhaps the most talented sculptor of his generation, the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial celebrates the heroic sacrifice and deaths of blacks who fought to win the Civil War. This artwork was a strident statement (at least for the late 19th century) that Black Lives Mattered. How quietly eloquent it is.

The piece was inspired in part by Saint-Gaudens seeing a painting, Jean-Louis Ernest Meissonie’s Campagne de France (1814), while he was in France. The painting depicts Napoleon on horseback with rows of infantry in the background. Saint-Gaudens wanted to be as realistic as possible in this sculpture, which was to tell the story of America’s first all-black military regiment. He took considerable time and effort to evoke the range of facial features and ages of the African American soldiers in the 54th Regiment. In fact, over the 14 years that it took him to complete the work, he hired about 40 African American men to pose for him as models for different soldiers’ heads. He was meticulous about the accuracy of the uniforms, including their insignia and details. Among some of the symbolic details on the relief: 34 stars along the top, which represent the number of states in the Union in 1863. The 11 x 14 ft. bronze cast was completed in May 1897, at the Gorham Company foundry in Providence, RI. It cost $7,000 to fabricate, about $225,000 in today’s money.

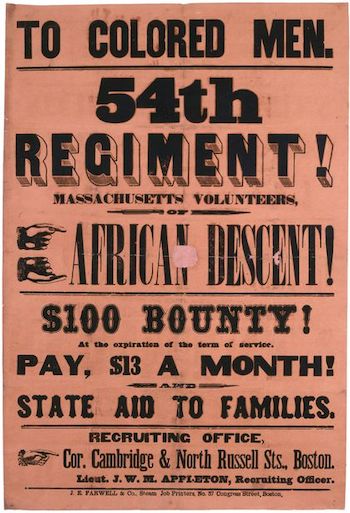

Recruitment Poster for 54th Regiment, 1863, National Park Service archives.

Traditional forms of civic or public art were, until the mid 20th century, figurative, and that included monuments, memorials, and civic statuary. Ranging from the human sized to the monumental, sculptures made to be permanent public art pieces were and are constructed of durable, easily maintained, and resilient materials that can withstand the worst effects of nature (wind, rain, snow, extreme heat, etc.), as well as most acts of vandalism. Bronze, steel, stone, etc. are seen as the most durable.

Though most civic art was often mundane bronze or carved stone soldiers on horseback or out-of-scale heroes, the beauty of Saint-Gaudens’s iconic bronze work is not just in its exquisite detailing and individually human depictions but also in its symbolic meaning. The sacrifice of African American soldiers was celebrated for the very first time via a sculpture filled with grace and honor. This spectacular artwork has yet to be equaled by other statues and memorials anywhere else in the United States. The sculptor’s art went beyond simple artifice; this is a profound image and object. Its soldiers were rendered as dignified human beings at a time when black Americans were considered by many as less than human, inferior to white Americans.

“Black Lives Matter” has become a mantra that refers to physical abuse, unwarranted deaths, and the disregard of the civil rights of black citizens by the police. Originating in the African American community, Black Lives Matter is an international human rights movement that campaigns against violence and systematic racism. The group speaks out loudly against police brutality, racial profiling, and racial inequity in the US justice system. Isn’t the 54th Regiment Memorial — an iconic piece of public art — a beautiful, strong, and prescient statement that supports these current notions?

Obviously, it is ironic that the 54th Regiment Memorial was vandalized during the recent protests. Luckily, due to ongoing restorative work, the bronze face of the piece had been covered by plywood. However, that covering, front and back, was painted with angry but unknowing graffiti. Perhaps the attempted defacement can be seen as a metaphor for our times — over the next few years, like our country in turmoil, this exquisite narrative sculptural relief will be going through much needed restoration.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

Tagged: Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Black Lives Matter, Mark Favermann

[…] But the removal (or attempted removal) of memorials to Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and even the Massachusetts 54th? How does that fit in? The revolutionary community demands the total reconstruction of society. […]

It doesn’t.

I like your eloquent words Mr Favermann. Thank you.