Opera CD Review: An Album of Beethoven Arias? Soprano Chen Reiss’s Imaginative New Solo Disc Pulls it Off

By Ralph P. Locke

Immortal Beloved is a CD that will appeal to lovers of fine singing and to people curious about some hidden corners of Beethoven’s output.

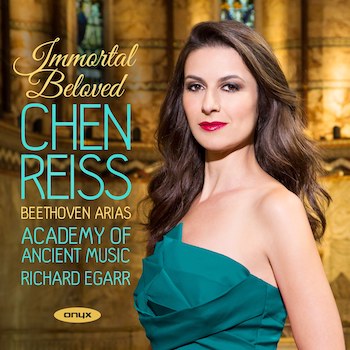

Immortal Beloved: Beethoven Arias. Chen Reiss, soprano, with the Academy of Ancient Music, cond. Richard Egarr. Onyx 4218, 59 minutes.

Click to purchase.

The story goes that one early nineteenth-century music lover left a performance of Fidelio saying, “That was marvelous! I really must get to know Beethoven’s other operas.”

Beethoven never did finish another opera, but he considered various librettos, and began one called [The Goddess] Vesta’s Fire, to a text by Emanuel Schikaneder (librettist of Mozart’s The Magic Flute). He also wrote songs or short arias, with orchestral accompaniment, to be used as part of what is now called “incidental music” for important plays and pageants or for insertion into a comic opera by some other composer.

Beethoven never did finish another opera, but he considered various librettos, and began one called [The Goddess] Vesta’s Fire, to a text by Emanuel Schikaneder (librettist of Mozart’s The Magic Flute). He also wrote songs or short arias, with orchestral accompaniment, to be used as part of what is now called “incidental music” for important plays and pageants or for insertion into a comic opera by some other composer.

This fascinating new CD is perhaps the first ever to have been devoted to Beethoven’s arias, theater songs, and other solo vocal numbers with orchestra. (The only place one can normally find them is in massive boxed sets claiming to include “everything Beethoven wrote.”)

Fidelio is represented by Marzelline’s delicious Act 1 aria imagining a happy life with Fidelio, who is in the employ of her father Rocco, a jailer. This “Fidelio” is actually the opera’s bold heroine Leonore, who has donned male disguise in order to try to free her husband from Rocco’s prison (where he has been hidden by a ruthless political enemy)

In addition to Marzelline’s aria looking forward to married bliss, the CD offers eight other wonderful Beethoven numbers, most of them relatively unfamiliar. From incidental music to the play Leonore Prohaska comes a song with accompaniment of nothing but a harp. (On YouTube, the same two performers can be seen doing the song “live” at the Austrian Cultural Forum, London.) We get two “scenes” or concert arias (written when Beethoven was a student, in, respectively, Bonn and Vienna). And there are two soprano numbers from the incidental music that Beethoven composed for Goethe’s play denouncing foreign tyranny, Egmont.

The CD opens with a splendid aria from a 1790 cantata honoring the accession of Emperor Leopold II (after the death of Joseph II). It features solo parts for flute and cello that are elaborate yet manage not to feel flashy in a theatrical way that might have been felt unseemly. The text invokes the Divinity as “Jehovah on Olympus,” thereby melding in a single phrase the glory of two very different eras and religious traditions. The disk closes with the oft-recorded 13-minute concert aria “Ah, perfido!”

Along the way, there are a few lesser numbers, including a charming arietta (for a Singspiel, or comic opera, by Ignaz Umlauf) about how tricky it is to get a new pair of shoes to fit right: “Soll ein Schuh nicht drücken.” This number uses a text by J. G. Stephanie, Jr., who, years earlier, put together the libretto for Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio. (The metadata promises a second Beethoven aria for this opera—“O welch ein Leben!”—but we do not get to hear it.)

Chen Reiss, a youngish lyric soprano from Israel, has already established herself in opera and oratorio across Europe. Her many roles have included Zerlina, Adina, and Liù, plus the soprano parts in the Brahms’s A German Requiem and Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Taken together, these give a sense of her strengths: smooth vocal production, ease in coloratura, and perfect intonation (that is, she sings on pitch, a rare virtue). Her first name may look Chinese. In fact, it is Hebrew and roughly equivalent to the English name “Grace.” (The “ch” in Hebrew is guttural, more or less as in German.)

According to Reiss’s online biography, this CD is the latest of nineteen on which she has participated (e.g., a Fauré Requiem conducted by Paavo Järvi) or which are devoted entirely to her. Her previous solo albums offer vocal chamber music with clarinet; art songs from the nineteenth century; and arias by, among others, Mozart and Cherubini.

It testifies to Reiss’s seriousness and intelligence that she here has assembled such an unusual, coherent, and thoughtful program. I notice that she has also performed the role of Marzelline in the fascinating—and in some ways preferable—first (1805) version of Fidelio, which is generally known as Leonore, to avoid confusion with Beethoven’s own heavily reworked and tightened, but also expanded, 1814 version. (I reviewed Opera Lafayette’s recent staging of the 1805 Leonore here. Jonathan Blumhofer reviewed René Jacobs’s recording of more or less the same 1805 version, finding it “revelatory.”)

Reiss, as I hinted earlier, displays great ease and control in legato singing and in the occasional coloratura passage or trill. Though the voice does not bloom gloriously at the top (like that of, say, Barbara Bonney or Carolyn Sampson), it never sounds constricted or the least bit unsteady.

What I particularly missed, at times, was more specific engagement with the words. This is, of course, most evident in items that have been recorded by prominent singers of the recent past. “Ah, perfido!” has been sung with greater dramatic variety and specificity—not least through frequent and sometimes drastic contrasts of tempo—by such diverse artists as Maria Callas, Cheryl Studer. and (my favorite) Gwyneth Jones. (All of them can be heard performing this work on YouTube or other streaming services.) Reiss is more contained and less varied emotionally. (In fairness, she becomes more expressive and word-responsive in the second recitative, before the quick final section.)

Similarly, the best-known number on the CD, Marzelline’s aria, has been rendered in perkier, more winning manner by, for example, Robin Johannsen on the aforementioned René Jacobs recording. Reiss’s earnest, straightforward reading seems to be intentional. Her booklet-essay describes Marzelline as “yearning, untried, idealistic”: a characteristically Beethovenian woman “reaching for ideals of sacrifice and courage.” But I’d say let Marzelline be Marzelline. I love her as she is—just as I enjoy, for who they are, the impulsive, too-trusting Zerlina in Don Giovanni or the adorable Dorabella in Così fan tutte.

Soprano Chen Reiss. Photo: Paul Marc Mitchell.

I was particularly glad to hear the more obscure items on the CD, especially the “tight shoe” song, which Reiss sings with extremely good German pronunciation, though not quite with a charming glint in her eye that would make the song come fully alive.

I should add that, from Fidelio, we do not get Leonore’s own aria (in any of its three versions). Perhaps one day a lyric soprano (Reiss or some other) will try it, giving us a reading that is closer in spirit to the eighteenth-century roots of Beethoven’s sole completed opera than do certain proto-Wagnerian performances.

In the scena “No, non turbati, o Nice,” Reiss carefully prefers certain passages that the young Beethoven wrote, rather than the corrected (but more conventional?) versions provided by his teacher at the time, Antonio Salieri. I wish she had also recorded the number a second time, for comparison, now with Salieri’s changes. The CD could have easily contained it, as it is only 59 minutes long.

Conductor Richard Egarrs is a much-recorded harpsichordist/fortepianist. He, Reiss, and the period-instrument Academy of Ancient Music (familiar from LP-era Mozart and Haydn recordings under Christopher Hogwood) make a good case for each of these works. Tempos are well chosen, and there is plenty of bite to the instruments’ attack, particularly in the military moments of “Die Trommel gerühret” (from Egmont). Yet there is not so much contrast in dynamics that one has to fiddle often with the volume control.

The ensemble plays with little vibrato, which may disappoint some listeners during the instrumental solos (e.g., in the aria from the Leopold Cantata). I sometimes felt that the orchestra was too quiet, as in certain pizzicato passages. But they play out mightily in the purely instrumental coda of “Ah, perfido!”—perhaps because they now don’t have to take a singer into consideration.

Translations of the sung texts are mostly adequate, but we could have used a clearer track list, with date of composition for each work. I was forced to read the two essays very closely, and double-check in OxfordMusicOnline.com, in order to get all the basic information straight.

In short, this is a CD that will appeal to lovers of fine singing and to people curious about some hidden corners of Beethoven’s output. YouTube offers an intriguing trailer showing excerpts from the recording sessions and from interviews with soprano and conductor. Reiss mentions there (though not in her essay) that Beethoven’s melodic lines often do not lie comfortably for the voice, and that she had to find ways to make them flow. It is a tribute to her high professionalism that one would never suspect the problem while listening to this frequently enlightening disc.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second is also available as an e-book. He contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, Bilbao, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).

Tagged: Chen Reiss, Immortal Beloved: Beethoven Arias, Onyx