Arts Remembrance: Christo, Master of Ephemeral Public Art

By Mark Favermann

Christo’s Art — Conceptual, Temporary, Monumental, and Always Memorable.

Valley Curtain by Christ., Rifle Canyon, Colorado, 1972. Photo: Wolfgang Volz/Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Christo was an artist who changed how we saw cities, buildings, bridges, coastlines, and islands. His environmental projects — from draping a curtain across a canyon in Colorado to wrapping a fabric around Berlin’s Reichstag — were usually grand in scale, disruptive, and transformative. They were controversial at worst, awe-inspiring at best. Christo, an artist like no other, passed away at the age of 84 at the end of May.

Born in Bulgaria in 1935, his family name was Christo Vladimirov Javacheff. From the early ’60s his collaborator was his wife, Jeanne-Claude (1935-2009), who was jointly credited on all the pair’s works over the last few decades. Christo became famous for his huge, site-specific environmental installations, projects that often took years, sometimes decades, to work out, given the challenges posed by engineering demands, political structures, environmental approvals, and governmental permissions. His artistic mediums of choice were usually nylon fabric with steel cable and fittings.

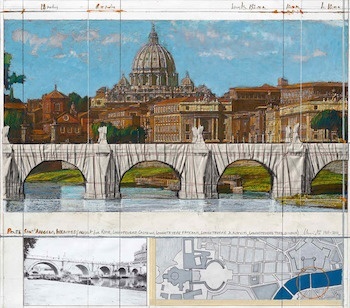

Drawing/Collage for Wrapping the Pont Neuf, Paris, France, 1975-85, by Christo.

Steadfastly independent artists, the couple refused grants, donations, or any public money. Christo was a highly skilled draftsman, collagist, and printmaker; sales of his traditional artwork pieces subsidized his ephemeral art projects. (Jeanne-Claude served as administrator and business manager.) Christo and Jeanne-Claude believed that the lengthy presentation and approval processes necessary for the creation of their art was an integral part of the experience. They also embraced the notion that their pieces contained no deeper meaning other than their immediate aesthetic impact. They created them because they supplied onlookers delight and beauty. These projects also exposed new ways of seeing and appreciating a location. Because of the comfortable accessibility of viewing their pieces, this kind of “land art” became the people’s art.

Christo’s creations were an alternative to traditional public art. Unconventional public art, Ephemeral Public Art, is defined as art in any media that has been planned and executed with the intention of placement in the public domain for a limited amount of time. Temporary public art started up in the early part of the twentieth century, coming into its own during the post-WWII era. Christo and Jeanne-Claude were among its greatest exponents.

Ephemeral Public Art pieces are generally community-involved, even evolved, and site specific with the goal of providing accessibility to all. They are often created with a multimedia approach in mind; a strategic relationship between content and audience is usually taken for granted. Frequently provocative, pieces like Christo’s challenge viewers’ sensibilities, making people rethink the urban streetscape, pointing out conflicts between the built environment and nature, generating concern about social engagement and justice. Antecedents to Christo’s pieces can be seen in the work of artist Marcel Duchamp, the Dada Art Movement, and Fluxus, as well as the “Happenings” of Allan Kaprow. Christo’s pieces were events as much as they were objects.

Through persuasion, persistence, and steadfast endurance, Christo and Jeanne-Claude somehow managed to pull off a series of distinctly gargantuan artistic visions. They overcame what, for many, would have been insurmountable obstacles. Understandably, some projects, such as Wrapping Reichstag, wrapping the Pont Neuf, and wrapping The Gates, took decades to accomplish. What’s irony about Christo’s art is that, while his pieces were made to be temporary, his creations continue to persist (almost magically) in our imaginations, staking out powerful spots in our memory.

Wrapped Reichstag by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, 1995. Photo: Wolfgang Volz/Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

While few of Christo’s projects were visited by the masses, they can be viewed because of extensive documentation through photography, film, and media coverage. Christo and Jeanne-Claude collaborated with photographer Wolfgang Volz for about a half century. An exception in terms of viewership was The Gates in New York City’s Central Park; over a few months in 2005 millions flocked to see the spectacle. Years were spent working on the project: its implementation coincided with a badly needed communal alternative to mourning over the 9/11 attack and its aftermath. Here, as with Christo’s other ambitious pieces, the concept was superior to what Duchamp referred to as retinal art, a form that he believed was intended to please the eye of the viewer. Though joyful and celebratory, The Gates was a mainly a work of conceptual art.

Many of Christo’s projects were festive, but a number were less than reassuring. Wrapping a structure, building, bridge, coastline, etc. not only conceals — it also reveals. Wrapping the Reichstag could be seen as an act of attempting to erase the past, to hide a barbaric history. Was this a ghost in a sheet or a potential unveiling of the dark past? Either way, there was an funerary aspect to the project. Wrapped Coast at Little Bay in Sydney, Australia was Christo’s first major piece (1969); a million square feet of coastline was covered by fabric for two months. Was this about environmental victory or defeat? Was wrapping this geography a way to showcase our depreciation of natural resources — or about potential environmental rejuvenation? It seemed elegiac to me — ecological assets as specter. Perhaps it was a critique of governmental oversight?

The Gates, NYC, 2005 by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Photo: Wolfgang Volz/Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

Another medium that Christo had been working off and on with since the ’50s were stacked oil barrels. His London Mastaba, a solemn sculpture of stacked, painted oil drums that floated in London’s Serpentine Museum’s Pond during the summer of 2018 was an awkward accomplishment, very much out of place. Rather soulless, this piece said little about the oil industry and even less about the pond site. It seemed to only be about congratulating bigness. However, most of Christo’s early projects were jubilant, generating an enormous amount of pleasure.

Interestingly, though aesthetically and personally very different, Christo shares some illuminating similarities with Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí: both are at the end of their aesthetic family trees. Their art works are spectacularly singular; future architects and artists can’t go much further in those directions. However, Christo’s greatness, like Gaudí‘s, lies in the epic expansiveness of his imagination, which will inspire others to dream ever bigger.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.