Arts Commentary: With Friends Like These — The New York Times Explains Why Criticism Matters

The important question the NYTBR Editors fail to ask is whether the traditional definition and values of literary criticism will survive in an age of ebooks and iPads. Is there a primal appetite for criticism? (Edith Wharton says there is, and I believe her.) How will the Internet shape our innate desire to compare, judge, and discuss books and literature?

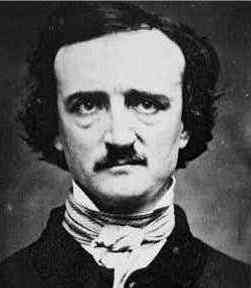

Edgar Allan Poe—The finest American book critic of the 19th century. The NYTBR’s “Why Criticism Matters” leaves him out.

By Bill Marx

It has taken me awhile to get to the six essays dedicated to the state of literary criticism in the December 31 issue of the New York Times Book Review (NYTBR), though I suspected that I didn’t have to rush. As Marianne Combs writes in her amusing Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) commentary, “the fact that this compendium has been published on what is widely considered the slowest news week of the year underscores criticism’s primary dilemma; critics still have lots to say, but nobody’s quite sure if anyone wants to read it.”

And, as she goes on to point out, the critics don’t really know who they are trying to interest. Is it their editors, bookish friends, and faculty members in New York’s mainstream journalism establishment, anxious to be reassured that the city’s cultural influence will continue? (Who will save serious criticism? We will!) Or is it common readers, even though some of the NYTBR contributors doubt that they exist any longer?

If the general cultural consumer is around, he will have his work cut out for himself slogging through these prosaic pieces. Modest about the critical will-to-power, shaken by the web’s armies of opinionators, the NYTBR essayists are far too academic and cautious to emit an inspiring clarion cry for the relevance of serious criticism. The iPocalypse, as contributor Sam Anderson calls it, need not fear. It is a disappointing round-up—with its rich history of raucous, passionate combat, journalistic literary criticism should go out with a bang.

In truth, the NYTBR editors pose the wrong question in their introduction to “Why Criticism Matters.” Given the spread of insta-opinion on the Internet, worries the book honchos, “where does it leave the critic interested in larger implications—aesthetic, cultural, moral?” The intellectual curiosity and range of literary criticism isn’t endangered today: you can write on anything you want at any length you want on the Internet. And since when does the ever-shrinking NYTBR bother to investigate these larger questions? Accusations about the NYTBR’s attraction to king-making, middle-brow fashion, and cultural logrolling have dogged the section since its beginning: Alfred Kazin, Irving Howe, and other first-rate reviewers, invoked as models by the NYTBR critics-on criticism, wondered if the NYTBR could stand much of the critical mind. See NYTBR editor Sam Tanenhaus’s review of Jonathan Franzen’s novel Freedom for a recent act of salesmanship masquerading as criticism.

For a scathing indictment of the cozy, book chat mentality, where publications have novelists review novelists, poets review poets, and editors hosanna the read-of-the-decade, turn to Edmund Wilson’s 1928 essay “The Critic Who Does Not Exist.” An excerpt from that piece or other provocative statements on the enduring value of book reviewing don’t make Jennifer B. McDonald’s NYTBR collection of “quotable passages” on the relevance of criticism. In her gathering of chestnuts and oddities (Walt Whitman as critic?), she manages to leave out a contribution from the most important American book critic of the 19th century, Edgar Allan Poe, a reviewer-of-genius who would recognize the problems besetting literary criticism today. He struggled in an age of anonymous reviews, meager pay for criticism, character assassination in print, editorial chaos, and a burgeoning literary opinion industry generated by a cut in postal rates for magazines. His passionate, articulate arguments for the relevance of book reviewing would blast the safe-and-sound NYTBR critics-on-criticism off the page.

The important question the NYTBR editors fail to ask is how the traditional definition and values of literary criticism will survive in an age of ebooks and iPads. Is there an elemental appetite for criticism? (Edith Wharton says there is, and I believe her.) In what ways will the Internet deal with the desire to compare, judge, and discuss books and literature? How will these methods be different from past forms of evaluation? How will criticism as independent and honest judgment fare in this transformation? Those are the real questions facing the future of arts criticism, and there are reasons for encouragement as well as fear—with less centralized power comes opportunities for more informative and fearless analysis. There’s also the possibilities for a chaotic and terminal free-for-all.

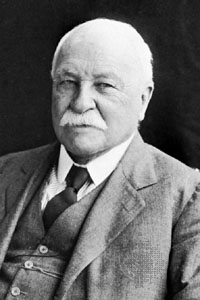

William Dean Howells — An American book critic who believed that the language of advertising was undermining the power of book reviewing.

Of course, chances are that instances of critical evolution won’t be found on New York’s established conduits of literary opinion, which so far have shown an interest in maintaining fading importance over innovation. The NYTBR team of critics-on-criticism won’t or can’t (Sam Anderson makes a stab at it) deal with the crucial challenge of the Internet because it hits too close to home. The days of the mandarin critic, thundering his or her marching orders to the literate masses are over, though some critics still act as if nothing has changed. How do literary critics garner respect in the age of the web? You are not going to get the answer from NYTBR critics-on-criticism, who write for The New Yorker, New York Magazine, The New Republic, and The New York Times. They don’t have to earn their respect from readers on the web—marketing departments and the cache of their respective publications do the work for them.

Thus the essays generally content themselves with reinventing the wheel. Katie Roiphe argues that reviewing comes down to writing well: “If critics can fulfill this single function, if they can carry the mundane everyday business of literary criticism to the level of art, then they can be ambitious and brash; they can connect books to larger currents in the culture; they can identify movements and waves in fiction; they can provoke discussion; they can carry books back into the middle of conversations at dinner parties.” But, as critic Clive James argues, reviewers anxious to have their critiques crash dinner parties are easily carried away with their words, often concocting beautifully phrased nonsense.

For Stephen Burn, the literary critic is above all else a supporter: “Stepping aside from the culture of opinion, delving deeper into open-minded analysis, critics might fulfill their most important function: locating major works that are not always visible in mainstream network.” Is that their most important task? If critics just champion the overlooked, who is going to do what critic H. L. Mencken says is the most valuable work of the critic—being negative, daring to say that the emperor has no clothes? What if one critic’s neglected gem is another’s dirtball? When does non-supportive become the best means to be supportive? It is a paradox as old as literary criticism.

Adam Kirsch insists that the critic eschew an arrogant will-to-power. The reviewer “participates in the world of literature not as a lawgiver or a team captain for this or that school of writing, but as a writer, a colleague of the poet and the novelist. Novelists interpret experience through the medium of plot and character, poets through the medium of rhythm and metaphor, and critics through the medium of other texts.” But a review proffers a verdict backed up by in-depth analysis; that is how it helps establish standards. How do critics remain honest and collegial at the same time? Is a reviewer a failure if poets or novelists see him or her as an intellectual antagonist?

“A serious critic,” concludes Kirsch, “is one who says something true about life and the world. The critic’s will is not to power, but to self-understanding, self-expression, truth.” But whose truth? Throughout literary history critics have been mistaken on many occasions about the books they judged. Reviewers should help readers understand literature and the pleasures it gives, not report on the therapeutic uplift fiction and poetry provides.

Refreshingly, Elif Batuman believes in the non-collegiality of serious criticism, but her argument is much too hard to follow: “Negative criticism is particularly exciting, not only because of schadenfreude, but because once limitations are identified, we glimpse how to transcend them. Learning the shortcomings of today’s neuronovel, we catch sight of the psychological novel of the future: a novel expressive of the problems we have now, including the encroachment of cognitive science into the concept of the self.” All negative criticism serves this role? Who is that “we”? Readers? Artists? Other critics? Why not start with the elemental reason for saying a book is not successful: by pointing out mediocrity, critics fight for more demanding aesthetic standards and send readers to worthwhile volumes. Most of the NYTBR critics-on-criticism seem uncomfortable with the idea of the critic as fault-finder; you get the impression that if they had their druthers they would only write positive reviews, which would enhance friendliness but rob book criticism of its independence and credibility.

Sam Anderson comes closest to dealing with the crucial problems the web poses for the future of journalistic literary criticism. He understands that the Internet raises radical challenges to conventional literary culture: “This has already changed the way we produce, read, share and digest our writing. Inevitably, it will also redefine what it means to practice book criticism, at least for those of us who aspire to write for something like a general audience.” We are dealing with moving targets—the nebulous worldwide “general audience” and the conception of criticism.

So what do book critics with an eye on the future do? What will this new definition of book criticism be? The query-filled answer Anderson provides isn’t particularly satisfying: “We have to work harder to justify our presence on the page, our consumption of readers’ increasingly precious attentional units. This means writing with more energy, more art, more conviction, more excitement and a deeper sense of personal investment. It means returning to fundamental questions: What is literature? Why do we read it at all? What happens if we don’t? The contemporary critic has to be an evangelist—implicitly or explicitly—not just for a particular book or author, but for literary experience itself.”

Sure, critics can work harder (for no money, of course) and better. But is that the extent of critical redefinition? In the future, writers will have to cultivate, via the Internet, our appetite for book reviews. What is criticism? What happens when we don’t read it? There will be experiments at reinventing reviewing itself. Defining literary criticism as a celebrator of the “literary experience itself” is unnecessarily limited. Criticism has always been about much more than that—reviews sold books and big critical personalities, slung gossip, drama, and ideas, generated dialogue on non-literary issues. Not all reviews sell literature—sometimes they educate the public about the essential value of critical thinking itself.

For Rebecca West, book reviewing should stimulate the life of the mind, thereby lashing “humanity to the world with thongs of wisdom.” You wouldn’t know it from the NYTBR’s wan compendium “Why Criticism Matters,” but some critics in the past garnered respect for their calling because they believed it to be a heroic undertaking. It will take that kind of daring-do to bring the expansive vision of literary criticism’s past into our technologically complex future.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Adam Kirsch, book-reviews, criticism, Elif Batuman, Katie Roiphe, Literary criticism, New York Times Book Review, Sam Anderson

A thoroughly good read, Bill. It’s one of the reasons I visit Arts Fuse and another that I don’t always finish what I start at NYTBR.

I’ve watched our Washington Post arts section become irrelevant. Not only are its best critics long gone but some of those who do write reviews focus on the writer (who cares?) and not what’s being reviewed or have no background in the subject. Last year, the Post did away with the separate book section and now when it does run reviews on Sundays, it relegates them to Op Ed. The rationale was economic, despite what the Post publicly contended. If we can’t all agree that the arts in their largest context matter, how do we answer questions focused on something more narrow such as criticism?

I agree that there is an “elemental appetite” for criticism. I don’t think it’s going to be fulfilled by newspaper critics (the few who are left) and writers for so-called “high brow” publications. And it’s for the better that its survival options are not limited to those media. To my mind, there is nothing that inhibits the translation to the virtual world of criticism’s “values”. I, for one, appreciate immensely the very fine writing I find on the Web, and when I hit on the site of somebody who can give me the kind of critical assessments I’m looking for, I keep going back and also pass around the word.

Like any other writing, criticism depends on the critic’s eye, sensibility and voice. The Times might have done better to ask readers to write about why they trust and follow the critics they do. I’ve found myself applauding many critics in the last few months: Heidi Waleson’s music criticism in the Wall St. Journal; Ben Brantley’s theater and Dwight Garner’s book reviews in the Times; and we’re big fans of All Things Considered’s Bob Mondello in our household — not to speak of our colleagues at the Fuse. All good critics work hard at specificity, trying to describe as best they can what they’ve experienced in an artistic work and its place in cultural context. They’re vital not only to audiences but to artists themselves. They’re in the same awful spot as artists, performers and writers themselves now: how will they earn a living?