Arts Commentary: Constraint in Quarantine

By Debra Cash

How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?

— Thomas Aquinas or some other wise guy, some other time.

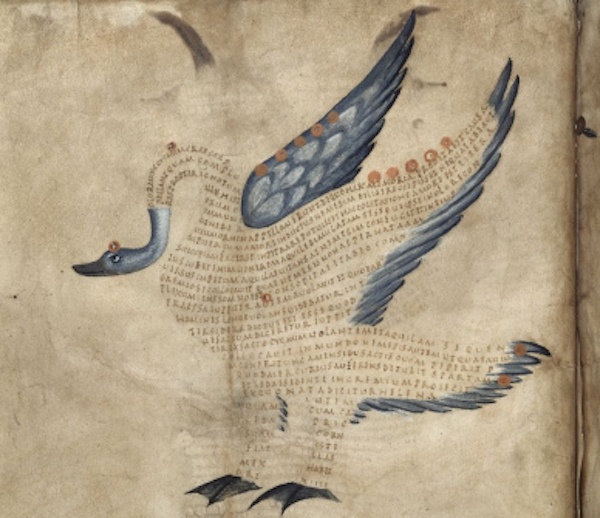

Medieval Micrography: an illustration of the swan of the constellation Cygnus, with text or scholia within the figure of the constellation.

Like you, over the past eight weeks I have been watching singers, actors, and dancers across a range of disciplines perform alone from their places of confinement. Their expressive languages – musical, textual, gestural – have been bracketed and shaped by the small windows of zoom or Facebook or Instagram lozenges, one camera shots made on mobile phones or through the lens of laptop cameras adjusted for tilt mid-gesture. Floating like islands in ether, juxtaposed in space (those galleries of pixelated headshots) or time (swoop to the next livestream, follow a random “up next” invitation down an attention rabbit hole, or click to repeat and reexperience the same captured moments), these slivers of sharing have seemed both too much and much too little. I long for the wide view, the ability to turn my eyes, as in a theater, to places where I did not necessarily expect to bring my attention. I want serendipity. I want expansion.

Yet even if our eyes are quarantined, our minds are not.

I’ve been thinking about the virtues of the miniature. A calligrapher friend who passed away in 2004 spent time mastering the meticulous art of micrography, an art form known to medieval Jewish, Muslim, and Christian artists who used letter shapes to create images that often served as either illustration or expansive interpretations of the texts they conveyed. Here are three birds.

A falcon in miniature.

Micrography is an art of compression. It conveys skill and discipline and whimsy and reverence. It is about beauty – and it is also about the grotesque. It is work that proclaims that you don’t need spaces to create complexity, and that staying still might allow for a pause that opens into wonders.

For dancers, there is something especially poignant about dancing in the limiting, sheltered spaces of a kitchen or a living room. During the very first week of shut down, the dancers of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre performed “I’ve Been Buked” from Revelations – each dancer home alone or in dyads (a few with pets or family members) and the dancing was rich in the resonance of lost theatrical space, the memory of forbidden live performance. These artists seemed to be caged birds, reaching for each other across virtual space, brought together only by the camera’s eyes and ours. Lots of Ailey fans watched this video, and cried.

Yet.

One of the most satisfying video dance sequences I have watched online during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a series of five solos by Brian Crabtree. None of the dances are more than three minutes long. Crabtree is a balding white man with dark caterpillar eyebrows; he has been an active choreographer in the Boston area since 1994. In recent years he has struggled with questions about how to choreograph and continue to perform in the context of an aging body and significant injuries. He moved to Peak’s Island in his native Maine this past year. When the pandemic hit, he took shelter in his friend Clyde’s home in Dorchester.

The bagatelles he has posted on his Facebook page take place in a living room with deep rose walls and a paneled white door, circular oriental carpet, and heavy Victorian bookcase topped with ceramic vessels. His dancing partner is one of a couple of carved chairs; one solo is “half a duet” he choreographed years ago. Somehow in keeping with the art of the miniature, he seems to be exploring (as he said about a prior work) how a noun can turn into a verb with simple inflection, and how gestures can both say specific things and be abstract, ambiguous signs.

A bird taking flight in a Medieval Jewish manuscript.

Crabtree presents himself as an ordinary man: turning his pockets inside out, counting on fingers, leaning against gravity as if to keep his seat on a roller coaster. In one solo, he turns a pair of wooden spoons into puppets and a lemon into a briefly rising sun. In all, the music is light classical and country melodic; his demeanor is deadpan, nonchalant. The idiosyncrasies of the details keep you guessing what he will do next.

You wouldn’t know, from watching him dance these personal, quirkily detailed investigations, that anything out of the ordinary was going on outside, that staying home had anything to do with staying alive.

I’ve already told Brian that I envision the post-pandemic life of this series as a gallery installation. Each solo will inhabit its own monitor and play on an unbroken loop. There will only be one set of headphones available per monitor, so that an audience member will have to experience each solo from a place of isolation. A piece of tape on the floor will keep the monitor and the person observing the dancing six feet apart at all times.

Constraint will be a memory we have to choose to reconstruct.

Debra Cash, a founding contributor to the Arts Fuse now serving on its Board, is Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance.

This is brilliant, and I will forward the article to dancer friends of mine. I will be looking up Brian Crabtree, and I so appreciate your concept of the art installation post covid. When you speak of your eyes being free to wander, in a theatre (rather than being restricted to the laptop screen as we find ourselves currently) I thought of Chagall’s ceiling in the Paris Opera House (which I have seen as an installation in a Montreal gallery). Its conception came from a wandering gaze of an audience member in an opera, who desired to see Chagall’s artistry taken from delightful costumes of the on stage actors, to replace the rather drab existing painting of the round ceiling…. and within a few years it came to be. Creativity originating with a peripheral gaze. Thank you, Raje